Ep 10 – Kennedy by Orbelian Part Two

Duncan Kennedy [00:00:08] And then there is the fact that in some long term run, the de-radicalization or deep politicization of a whole generation was sort of finally fully being realized. There are a million different kinds of explanation. But cultural, large, generational deradicalization means that when you destroy the cultural capital, you don’t have all this stuff coming along to build it upright again so you can destroy the cultural capital, and then, if the resources are there and as times favor it, you can reconstruct it very quickly. But in this case, there wasn’t much to work with after the capital was destroyed.

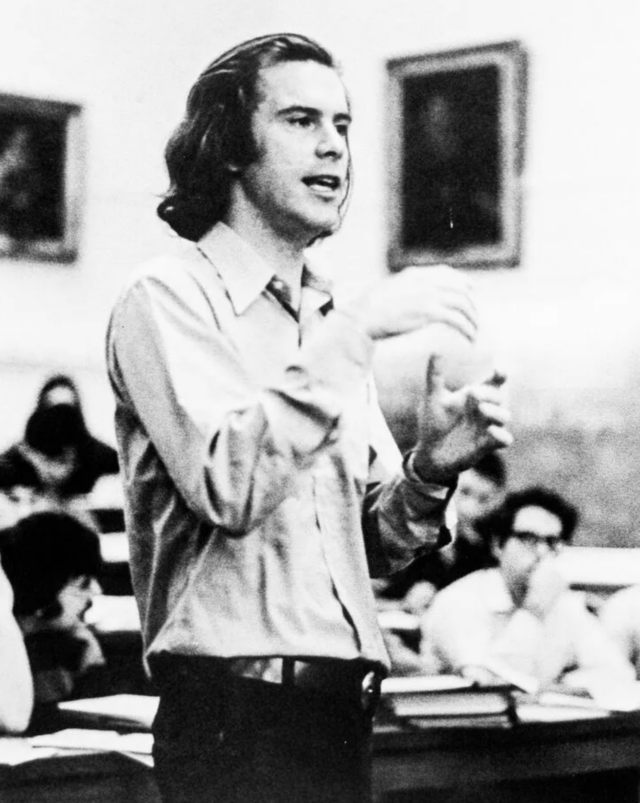

Jon Hanson [00:00:50] Welcome to the Critical Legal Theory podcast, where we hear from legal theorists and practitioners about the origins and effects of critical legal theories. I’m Jon Hanson, the Alan Stone, professor of law and Director of the Systemic Justice Project at Harvard Law School. In the previous episode, you heard the first part of Craig Orbelian interview with Duncan Kennedy. In that episode, they discussed Kennedy’s 1981 Root Room talk, which would form the basis of his essay “Rebels from Principle.” This episode contains the second part of that interview. Here they discuss Kennedy’s 1983 work, “Legal Education and the Reproduction of Hierarchy, a Polemic against the System.” In it Kennedy critiques the various ways the American legal education system contributes to and reinforces gender, socioeconomic, and racial hierarchies. Kennedy touches upon ideas such as the impacts of radical law-student activist groups that organized against administrative bodies and the broader institutions as a whole. During the 1970s and 1980s, potential contributors that spurred a generational de-radicalization of those leftist student activist coalitions in recent decades. How CLS scholars and other cultural critics’ critiques of law school classrooms contributed to reforms in the repressive hierarchies found in those spaces. What it has looked like to shift away from the more traditionally brutal pedagogical regime towards a more liberal, softer style of teaching. And finally, Kennedy considers and discusses law professors techniques aimed at combating the “gunner” hierarchy and some of the drawbacks of these approaches. Resistance as a habit and not just as an activity and what it meant by CLS members acting in their own interest. Throughout this episode, you’ll hear Duncan refer to people, events, and scholarly works that impacted or interacted with class. You can find more information about most of those topics in the links in the show notes on our website. Here’s the interview.

Craig Orbelian [00:02:56] We were just talking a little bit about leftism and more broadly changing institutions, and I think that’s a good segue way to work that you came out with the year after in 1982 and 1983, which is “Legal Education and the Reproduction of Hierarchy.” Would you mind taking a moment to describe a main idea that you’d like posterity to take away from the piece as you look back on it?

Duncan Kennedy [00:03:28] Well, the part of the whole thing that I actually like the best is the attempt to evoke the quality of student existence in the first year. The set of vulnerabilities, anxieties, hopes, as it’s shaped by a particular institutional atmosphere. And the single thing I like best is the description of the guy law student with a moot court partner who is a woman thinking about his relationship between the court partner and his wife and him in the context of passionately preparing, staying up all night, doing the moot court thing, which is very evocative of the time. So that’s 30 years ago when there were many fewer women law students, and when the norms of interaction between men and women, the sexual politics of legal education, were really, really different. But I still think that even a person in today’s law school can see the bite of what that experience might have been like for the woman, for the law student, the wife and the husband. So that’s the single thing I like best about it. An idea at a more abstract level would be that [00:04:43]you can analyze the system of legal education. This is a sociological idea that the system of legal education taken as a whole in many, many, many of its different institutional aspects, everything from the first-year classroom, to the moot court, to the interviewing process, etc., etc., etc., can be understood as one of the things that leads to a situation in which the bar is stratified, lawyers are stratified, law firms are stratified, lawyers are in a stratified relationship to other aspects of the population. And wow, it’s a mirroring process. So there’s both a functional thing. The law schools are turning out people who will be integrated into it reinforce this system of hierarchy. The system is persuading them to accept it, and it’s doing it by reproducing inside law school hierarchies, which are analogous to the hierarchies outside law school. So the three ideas as sociologically, it is a production that the hierarchy of firms, the hierarchy of lawyers, the incomes of lawyers, the jobs of lawyers, they’re highly hierarchical. Ordering is something that gets is made more possible, more likely and more plausible by legal education that legal education trains students to accept, enjoy it, and that it does it by mirroring. That’s the icing on the cake, so to speak. That’s the professor is the partner idea. The professor is the partner. Meaning it’s an initial modeling of what will later be the relationship of the partner. [101.4s]

Craig Orbelian [00:06:25] In both the partner associate relationship and the professor student relationship, there seems to be a similarity in the form of a certain kind of hierarchy. I was wondering if you could describe for the listeners how you would define hierarchy.

Duncan Kennedy [00:06:45] Sure. Hierarchies come in many, many different forms, but the basic idea is that there are two people or a very large number of people who differ, not just in some objective attribute that can be measured more and less, say more or less income. But the difference in the objective attribute, which might be income, it might be job employment, it might be education, has about it two further aspects than the factual differentiation of people on a quantitative scale, one of which is the idea shared by people, not everybody, but a significant number of people that the differences in the quantitative thing more money, more power, better job, more education are reflective in some sense of value, not the value of the thing. It’s not the value of the money. It’s that the people with more money have more money because on some level, in some way they’re entitled to it, they’ve earned it, or they deserve it, or they’re better or whatever. So that’s the first thing. And the second thing is power, that the hierarchy is not just a differentiation in terms of the amount of some quantifiable thing because power isn’t like that, that in this ordering of people, the people who have more of the thing also have the power that allows them to reproduce the system, not them only. The whole system. [00:08:11]But of course, hierarchies can be legitimate or illegitimate, and legal education or reproduction of hierarchy is whole elaborate paragraphs about how it’s not all hierarchy that’s illegitimate. There are some hierarchies that are illegitimate and some that are legitimate. So that’s a very important part of the theory. It’s not a theory of leveling in the pure sense in which you just say all differentiations of both the quantitative rank order and then the legitimacy and the differences of power are abolished. [29.0s] No. And a person like myself who is a father and a grandfather would begin by saying that there’s nothing more legitimate than patriarchal paternal authority. And I expect my children, even now in their forties, to acknowledge the truth of this basic maxim of society. That would be for starters. Then here’s an example of an illegitimate attack on illegitimate of hierarchy, the radical mental health movement, which was a very, very important movement of the sixties, particularly [00:09:10]R.D. Laing. [0.0s] Unbelievably brilliant critique of the hierarchy between psychiatrist and patient. And they took it really very far. They tried to reconstruct their understanding of the therapeutic enterprise as completely egalitarian with people who were seriously psychotic. It was not good. I mean, it produced an enormous amount of suffering to fail to realize there was just this fundamental difference of capacity. That’s another example. The relationship of doctor to patient, of therapist to client can be legitimate, can be highly legitimate. The relationship of lawyer to client can be a legitimately hierarchical relationship, in my opinion. So I don’t have any doubt that the professional ideal is an ideal that’s organized around the construction of legitimate hierarchies, which have very powerful fiduciary duties running in the opposite direction from the experiences of extreme dependance. I don’t think this is very problematic. I mean, basically the question is how do you apply the distinction to the hierarchy of law schools, for example? So I think the first basic question is, is the hierarchy internally morally humane and legitimate? And the second is what are its impacts outside itself? [00:10:25]So the hierarchy of law school strikes me as totally illegitimate. And one of the proposals was that law teachers and law students should be assigned to law schools at random with a cutoff point. [10.9s] So you couldn’t get into the pool unless you were as good as the students who get into the pool at the bottom now. So everybody above that level is in, and then you have regional preferences and other preferences, too. I mean, if you can show that, you know, your grandchildren live there, so you want to go to the law school there, even it’s outside your region that would create law school faculties that were not organized according to the current hierarchical order and with a permanent destabilizing element because of the random selection. Two major objections there is made is, you know, the people in the better law schools are better people, better teachers and better students, and they have an entitlement to be with each other. Bullshit. The second is all the laws would be the same, which is ridiculous. I mean, we’re given the laws of small numbers that would be wildly different and they change all the time. No, this was an important proposal in this sort of set of proposals. One of the things that always fascinated me was people would say, well, name a single institutional order that has ever been like that. To which the answer was Little Switzerland has it. As of 1980, there were like six Swiss law schools. They had no recognizable hierarchical order, and students didn’t choose between them on the basis of which was the best one. “Yeah, but Switzerland. What’s that got to do with the United States? I mean, that’s ludicrous.” Well, the question was, can you imagine that ever happening? And has it ever happened? Well, I like the Swiss model, by the way. Probably neoliberalism has changed the Swiss system to one where they’re user fees and inherited wealth is the basis of admission with stacked LSATs that claim that only the best are the best I don’t know. That was 1981.

Craig Orbelian [00:12:19] Also in Legal Education and the Reproduction of Hierarchy. You mentioned that in the US, ideology, “is a particularly important instrument of domination.” And I was wondering if you could comment on what makes ideology in the US particularly important compared to ideology and other places?

Duncan Kennedy [00:12:44] Well, that’s a gross sociological generalization on my part, for which I have no basis whatever except the merely anecdotal. So it’s based on tourism. I mean, in other countries and tourism inside the United States. But that comes from a background kind of critique or analysis of American society, which would say something like and this is a long tradition of puzzlement by American leftists: unbelievably unequal society, much more — at the time I wrote this it was still the case, but this is less true now that the United States was — radically more unequal, more caste segregated — that is, not only race, but also ethnicity of various types–, more class segregated, very limited upward social mobility. The United States was and is a very tightly hierarchically ordered society compared to the Western European societies that embraced other forms of the welfare state and other forms of meritocracy than the United States. So a basic leftist question has been historically, why no socialism in America? And in a sense, I’m just repeating the idea that the reason why there’s no socialism in America can’t be that there’s no reason for it. I mean, huh? It looks as though compared to, say, France, the U.S. should be full of crazy leftists. France, by comparison, is, you know, idyllic. It’s got big, big, big problems. They need more labor flexibilization — not. So there are obvious problems. They have a large, now, a large underclass, much larger than it was in 1970, say. Why then no socialism in America? And then an answer that many leftists, whatever that means, tend to give would be something like: “In America it’s amazing how much legitimacy the system has for people who look from this perspective as though they’re being fucked over from it.” So you can say, “Well, wait a minute, who are you to say whether they’re being fucked over? I mean, basically, isn’t that a complete false consciousness kind of Marxist attribution insistence that, you know what, people’s welfare is better than other people?” “Yeah, but I mean, basically we’re talking about a system in which just look at the distribution of income. We don’t have to be, you know, rabid paternalists to say you’d think it would make them a little pissed off that they don’t have any money and that, you know, the top 2% of the population controls 50% of the wealth.” I know that’s a slander. The top 2% does not have 50% of the wealth, but it’s certainly in the ballpark. So that doesn’t seem like an extreme claim to know what’s good for other people. When they don’t agree with it themselves. But they don’t seem to be as pissed off as we, the enlightened leftists, would have expected them to be. So what do they say? They have explanations of why things are okay. That’s the ideology. From this point of view, when the explanations seem to be false, like, “well, we have equality of opportunity in America. So it may be true that I haven’t done well, but it’s basically a free country and people who deserve it can make it here or you can be anything you want to be.” So you go every Sunday in the beginning of the sermon. At the end of the sermon. You can be whatever you want to be. So this is a kind of interpretation. Which attributes… these are ideological ideas — so “we are a society of equal opportunity,” “you can be what you want to be” — that seemed to have an important explanatory explanation for something that a dog that didn’t bark. Why didn’t this dog bark? Well. I don’t know why the dog didn’t part. I really don’t. I don’t claim to be omniscient. I have no real idea. But it seems like these beliefs play an important role.

Craig Orbelian [00:16:46] In the 2004 Introduction to Legal Education and the Reproduction of Hierarchy, you look back on the movement and you say, “It would be a good idea for different types of activists,” I’m paraphrasing “to find a way to hook up with one another and protest inside law school against law school. I had a better idea of how that might work in student faculty coalitions in 1983 than I do now.” I’m wondering how it’s become harder to think about activist collaboration.

Duncan Kennedy [00:17:30] [00:17:30]That’s a complicated question. It’s very interesting to me because a lot of my life in those days was involved with collaborating with activist groups of students. So I had a fairly intense series of experiences over really about 15 years of working with student groups that were doing everything from sitting in in the Dean’s office to advocating a no hassle pass to whatever. [22.4s] There were many, many different student issues, and I want to distinguish between two aspects that was very carefully chosen words. So I didn’t say, I don’t think it’s possible or as possible today as it was then. I really didn’t say that, and I didn’t mean it. I know we get back to all the other stuff that we were talking about at the beginning of the interview. It’s a common idea that nothing can be done, just like you go to the corporate law firm and you’re a cog or you’re a judge and you’re a cog. So the idea that in the current context, law student activism is simply structurally impossible is a very similar idea. And just as I don’t believe in those contexts, I don’t believe it in this context. So what I was carefully saying was I find it easier to imagine — now at that period I was involved with lots of student groups that were doing things like that, not as a role as a leader, but as a coequal, violating the norm that faculty and students shouldn’t collaborate on activist projects that are aimed at the school. I was doing that a lot and I had a strong sense of when the students were likely to do things, quite a bit of sense of what they were likely to do, and I was totally happy to consult with them. And we had our own activities which relied to some extent on student support. That situation doesn’t exist at Harvard Law School today that I’m aware of. I don’t think there are anything like the number of students with activist projects oriented inside the school. I’m not sure what the numbers are with activist projects oriented outside the school. But important thing about 1983 was the students who worked in the Legal services center in Jamaica Plain were then going to be a good quarter of the personnel to sit in the dean’s office over hiring a black woman. So the inside outside distinction was not really, really sharp, certainly a lot less sharp than a situation where many say human rights oriented students are working incredibly, bravely and boldly say in the Gaza Strip, that’s a lot further, so to speak, from the dean’s office in this sense than Jamaica Plain. So I’m not sure. First of all, why is it true that there’s so much less and what are the possibilities and conditions that would make it plausible for that to happen? So it was a genuine expression of not hopelessness, but just distance. [00:20:17]One historical event that was important, some sometime in 1991, 1992 and 1993, there was a moment of student activism actually peaked after a long period, ups and downs backs and forth, but at a fairly substantial level, even with fluctuations. There was a kind of explosive moment in 91, 92, 93, which generated a kind of bubble popping. It was like 1970 or 1971 for leftism in America in general. There’s some moment when it got spun out of control, got too intense. People really, really got mad at each other. There was a deep sense of poisoning among leftist activists and vis a vis the mass of the student body and the faculty was incredibly, bitterly divided. These things are weird, so it’s just that the randomness of history produces, at that moment a kind of crisis in which all the accumulated capital of organizing over a very, very long period, 15 or 16 year period, the accumulated capital was destroyed. The students and the faculty and their faculty collaborators and so forth produced a kind of implosion. [77.2s] Right away, you know, it was immediately obvious. The next year the number of people interested in these activities just plummeted. The number of interactions among them really declined. The number of people with any kind of a left identity disappeared. [00:21:48]So that’s a very contingent function of the unfolding of events at the school during this period. But it also corresponded to the election of Bill Clinton, the symbolic significance of which could have been one of many things, but a basic significance for liberals was things are going to be all right again, we hope. Whereas a lot of the power of student activists and they’d come from disillusionment with liberalism, followed with disillusionment with Reagan Bush. So that sequence was first disillusioned with the failures of the liberals in the seventies, but then very much rage at the right. Then Clinton comes in. There’s this explosive moment, but the background of the political situation is that that was demobilizing in a very, very basic way. And then there is the fact that in some long term run, the de-radicalization or deep politicization of a whole generation was sort of finally fully being realized. [59.5s] There are a million different kinds of explanation. But cultural, large, generational deradicalization means that when you destroy the cultural capital, you don’t have all this stuff coming along to build it upright again so you can destroy the cultural capital and then if the resources are there and the times favor it, you can reconstruct it very quickly. But in this case, there wasn’t much to work with after the capital was destroyed. This is normal organizational terms in the sense these are connections between people built up over time and practices that are transmitted from one generation to the next. No transmission occurred and no new people committed to doing it appeared. [00:23:29]Now, that was a long time ago. That was 20 years ago. It’s never taken off again in anything like the way that it was there until then. [7.9s] Another generational factor. There are other factors. It’s very interesting. But again, let me emphasize that I’m not in my twenties. I’m in my seventies. My children are in their forties, so I don’t have much access. It’s a very basic idea.

Craig Orbelian [00:23:56] Another comment you make in the introduction to the 2004 edition of Legal Education and the Reproduction of Hierarchy is, and I quote here, [00:24:06]”Resistance is an attitude that turns into an activity that becomes a habit. And pretty soon it’s like the habit of exercise and you feel bored and unused when you aren’t making trouble for someone somehow.” [14.1s] Over the years, have you felt that certain of your acts of resistance have been more strenuous and have been better at keeping you in good shape? Resistance wise?

Duncan Kennedy [00:24:37] I like that quote, by the way. If I do say so myself, I really don’t know how to answer it. So some acts of resistance now. I love them all equally. The baby acts of resistance are all to be cherished over time. But I’ll give you an example of the experience that I’m talking about there. Well, okay, here’s some ones that were great. Cambridge rent control rocked. That was really a cool experience of combining my Cambridge localness with my Harvardness, with my contacts and my housing work to be just, you know, a line participant — that is, not a boss because I wasn’t a political leader — but just one of the people devising strategies to try to save Cambridge rent control as landlords attacked it successively all through the eighties and eventually succeeded in knocking it out. Why was that so satisfying? I think it was because it broke a little bit out of the bubble. So the bubble for me of law school, everyone lives in a bubble. But it was very satisfying and very invigorating to actually be out there with the people who lived in rent controlled apartments and then the old Cambridge lefties who had been there since rent control came in in the sixties were still there fighting the rearguard battle. That was really great and it was very invigorating. Recently, the experience of this type, that is by far the most strenuous but also exciting has been Israel-Palestine work, where because my basic background attitudes are very critical of the state of Israel and of Israeli governments of the recent past and very sympathetic to many, many Palestinian claims, I’ve had the experience that the resistance is likely to produce a very strong feeling that you’re resisting something very, very powerful in the U.S. So in the U.S., to take these positions is to experience what it’s like to be once again in a position of opposition to a very, very organized and powerful force. [00:26:44]And that has been very, very invigorating for me. And much as with many experiences of resistance before doing it, before doing these things, one after the other, I’ve always felt scared. So even Cambridge rent control was scary. Our house was egged by supporters of small landlords of Cambridge who were claiming that they’d invested their fortunes and that rent control was ruining them and blah blah, blah. So this moment of scariness is a very important quality of it. Some people like that, some people really hate it. But over and over again, my experience has been that I was more scared than I needed to be. That just means I’ve been lucky on one level. Just means I’ve been lucky. But also I think it has always reflected in me a really terror of jumping into the cold water. So standing on the dock saying, this is just going to be intolerable, I don’t know if I can bear it. Am I going to do it? I’m not going to do it. Imagining the horrible shock of the water, I mean, you’re not going to die when you jump into the cold water, but it really, really is freaky. So I’ve had that experience very often with these moments of resistance. And the moment when you jump, it’s very satisfying, even if it really is very cold. And then after the fact, you get out of the very cold water and your body is just reacting to the warmth of your body is generating as a result of the shock of the cold, it’s very, very powerful experience. So this is not exactly the exercise analogy because it emphasizes the problem of fear as a very strong force for me in my own life, in my own activity and the problem of overcoming it, it’s a central different aspect of resistance. [103.2s]

Craig Orbelian [00:28:29] I’d like to fast forward three decades to Abby’s interview a few days ago in 2013. And in Abby’s interview, you mentioned some techniques that you used as a teacher in the law school classroom for combating the gunner hierarchy. You mentioned that there are certain techniques like avoiding calling on gunners and calling on students sequentially seat by seat. You said there are also many more techniques. Can you name some of those techniques and talk a little bit about how you devised some of them over time if you needed to devise new ones as your teaching style developed, or as the classroom dynamic changed?

Duncan Kennedy [00:29:15] Well, that’s apropos because on Friday, last Friday, I had a very bad class in which one of my gunner techniques totally backfired on me. So the one that I didn’t mention, the next one in my list would have been the technique of having a question posed, asking students to discuss in small groups of four or five around their seats. Choose a spokesperson to answer the question and then asking for — if it’s a big class, there will be 10-12 groups, but if it’s a small class, there might be four five — then asking the spokespeople to give sequentially an answer to the question without feeding back till the end. Then the spokespeople can’t be the same in the next time you do it. So different people have to be the spokespeople. So that technique I’ve had sometimes great success with. But last Friday I had this experience with that technique. They just wouldn’t choose the spokespeople. So I could see that really serious resistance to the technique had built up. They were sick of it. The class was sick of it. There’s a class of 80 people, and they just basically wouldn’t do it. So the choose your spokespeople, the groups just failed. So this group, who’s your spokes people? They looked at me. They couldn’t choose a spokesperson. Now this means they’re pissed at me. The basic meaning of this is anger at the teacher. So that’s an example of a technique that is often worked incredibly well, just not working. So here’s another technique that sometimes works and sometimes doesn’t. So going down the row, the idea of going down the row is you go down the row and you say you can pass. If you have a headache pass, if you’re bored, If you weren’t paying attention to the last thing that said, just pass. You have a long row of students, and when it works, three people will pass and then a person will talk and then two more people will pass and then three people will talk. And who talks is highly unpredictable because the person who is willing to talk when other people have passed could either be a gunner or a person who says, “I have nothing to lose. All these people have punted, so why shouldn’t I give it a try?” Here’s what happens when it doesn’t work. Everybody passes. Again, this means that something has changed in the ethos and now you’re in trouble. So after this class in which both of these things happened, I am now in trouble. So a basic question is, do I have to resort to the gunners? I know the gunners are there. I need. I’ve already identified the gunners. They were just waiting for this to happen. They hope that my situation will now be that in despair. I’ll ask the question and wait for people to raise their hands. At which point the class the non gunners will not raise their hands. They will sit there loathing the gunners, but watching them as a result of the complex sort of psychology of the gunner in which you hate the gunner wouldn’t want to be a gunner. You hate the gunners so much you wouldn’t raise your hand because then you would be a gunner. But then blah, blah, blah. So those are two techniques. So those techniques are sometimes successful and sometimes unsuccessful. They’re not panaceas. Not calling on the gunners is very basic, but that requires you to do something sometimes dramatic. You shouldn’t ask an open question unless you’re ready to deal with the possibility that only gunners will raise their hands. So if only gunners raise their hands, what are you going to do? You can call in a gunner or this is a technique. Just not call it a gunner. Silence. Or say, I really appreciate your contribution in the last thing you said was really, really good. But I think I’m going to ask you to take a pass this time. That’s another technique has to be really, really nice. But it’s possible to do it really nicely. Another technique this is very hard to do, and I’m again, I’m very unevenly successful with these things, is to introduce the class, to have a framing for the class or the materials for the class to have a revealed lesson plan. So a revealed lesson plan is my own agenda for the class. Attempt to state it briefly clearly in two paragraphs and distribute it before the class in the form of “This is what I’m trying to get across in this class.” Now that turns out to be very rare in this pedagogical context because it’s putting the teacher too much into the mix for the norm, which is “You have the materials. I’m going to help you get out of the materials, what there is to be gotten out of them” as opposed to “this is what I would like you to get out of the materials.” And then a question could be how did the materials fit the lesson plan? Now, again, the first person who will respond will be a gunner, But the question changes the terrain. It’ll make it harder for for some reason. Don’t ask me why this is. That one is tricky for gunners. It puts them in a slightly different position than just answering the teacher’s question out of the materials, and it makes it slightly easier for non gunners because it’s an interpretive question in which they can try to answer the question, “What were you driving at?” Rather than the question of “what is the correct answer to my question,” those are the ones that come to mind. But I’m emphasizing that the commitment of students to the complex of back bencher masses and gunners, their commitment to the structure is profound. So it is extremely difficult to fight it. And the difficulties of fighting it never go away because it can reassert itself at any moment.

Craig Orbelian [00:34:59] Have you noticed that over the years you’ve had any progress at all in combating the gunner dynamic?

Duncan Kennedy [00:35:07] Well, I mean, it’s not cumulative, right? You mean I’ve gotten better at it?

Craig Orbelian [00:35:11] Maybe you could get better combating the gunner dynamic as a teacher in an individual class, but also maybe over the decades, teachers like you have done something to change the perceptions that students bring to the classroom where they no longer expect that they’ll be either a gunner or a backbencher. They’ll start to think that maybe the law school classroom leaves room for people in the middle to participate. Do you find that over the decades the gunner dynamic has started to recede a little bit?

Duncan Kennedy [00:35:52] No. I don’t. I mean, I don’t know. I don’t feel that way at all. Not at all. And I think many of the aspects of reform and progress in the law school classroom since I wrote Legal Education and the Reproduction of Hierarchy, some of which I think we were responsible for, that is, I think the crits and the other cultural critics of the classroom had a major impact on it. Also, generationally, by reducing the number of hardass, terrifying teachers and legitimating a much softer style. In the prior regime, there were no gunners, there were stars and pets. So stars and pets — different from gunners because in the cold call universe, many people are being cold called on during a class and their contributions are being, in effect, micro marked, micro evaluated through the teachers body language and what the teacher says in response. So lots and lots of people are being marked every day. There’s very limited discussion, hand raising, and the pets and the start — a pet becomes a star that is in this random process of calling, a student is rewarded by the teacher repeatedly. That student goes from being a star, first a star, then a pet. So a star, then a pet when the teacher indicates preference by, for example, if there are hands raised calling in that student, not the gunner who is the one with their hand up, but there are ten students and the pet gets called on when the teacher wants the right answer from star to pet. So that structure is almost completely gone. It’s been liberalized. It was experienced, as incredibly cruel. It was very alienating. Many teachers abused it, and it was culturally completely condemned by the Sixties. So the whole idea was this kind of thing is intolerable. So liberal styles took over. Liberal styles radically get rid of this idea of the hierarchical cold call, the brutal grading every student every time, just completely inconsistent with the idea. It’s supposed to be a much more collaborative, discursive, and dialogic process. So the gunners become the rulers of the roost. That is, this is not the whole explanation. But now the teacher is putting himself or herself at the mercy of students willingness to participate, as opposed to the prior style where the students are at the mercy of the teacher’s demand for participation. Now, the teacher has rendered himself or herself vulnerable because the teacher wants it to be participatory and the opposite of the old style. Then the teacher is going to respond to people raising their hands, experiencing the real problem that nobody will respond. Terrifying moment. You ask a question and nobody responds. When the gunner responds, the teacher is incredibly relieved. It gets horrifying maybe when it’s going on for days and days and days and the same six gunners — there are 60 people in the class and six gunners are doing all the talking, but it’s basically locked into the psychology of the situation. And then what happens is the development of the student culture in which contrasting Harvard Law School with Suffolk or the New England School of Law, both of which places are taught. It’s really, really different. There is infinitely less gunner culture at New England and at Suffolk than there is at Harvard. So we need an explanation of why it would be that at both New England and Suffolk, it really is true that students who never talked before will, on day three, suddenly they’ll talk and someone else will talk. The gunners are there, but they’re actually sort of disciplined in a completely different way by the group because someone will raise their hand to just disagree with a gunner. Students are much more free to disagree about solutions. So you ask a question, student A says, “I think that,” another student will raise his or her and say, “I don’t agree with that answer.” These are things that never happened at Harvard, ever. [00:40:03]My interpretation is the problem of the elite. So the problem is you’ve been number one, you’ve been the pet, the star, the top performer over and over and over again. Then you didn’t get into the Yale Law School. Then you arrive here and it’s obvious everybody can’t be that way. So the basic situation is you would love to be that once again. You would just love to. It’s too risky. It’s dramatically more risky now you’re not going to be the one in all probability. The logical, rational response is not to risk it. And then there’s the problem of the gunner doing it. And when the gunner does it, the gunner is doing what you would most like in the world to do and what you’ve done throughout your life as a student since you were in elementary school. And there it is. And you just feel revulsion and rage and loathing, which is really complicated. It’s partly because you would like to do it. It’s partly because your repression of your desire to do it is an incredible loss. “This person is doing what I’m not doing. If I were an asshole like him, I’d be doing that too. But I am not an asshole.” [75.0s] So it’s a very, very strong psychic thing. And that means no participation, because then you look at other people and as soon as a person talks, you feel that rage at them, and then you’re never going to talk. Once you recognize yourself in the eye of the other, you say, “No, no, no, I’m never going to talk.” That’s just a guess. That may be totally wrong. It’s just a way of thinking about it. I’m not saying that this is the truth of the matter, but it’s so striking the difference between the schools. So the low status schools, basically students are just much more fun to teach.

Craig Orbelian [00:41:53] In Abby’s interview, you mentioned that CLS members act in their own interests. Can you explain what you mean?

Duncan Kennedy [00:42:01] I think maybe I can give an answer that would be some clarification by going to the idea of CLS being a movement in which people are looking after their own interests. So that’s a very ambiguous statement. The first idea there is it’s not selfish self-interest in the sense of, let’s say, being bribed or the sense of wanting to maximize your income. The idea is in your interests with respect to the ideal question of the organization, of the institution, and of daily life. So the interest here is what they were calling an ideal interest. It means the people in the law school, the people in this case are a minority who object to some aspect, let’s say, of the way the curriculum is organized or some aspect of the way older professors treat younger professors, or some way in which professors treat students who they identify with. So the basic idea here is the CLS people are acting in the interest of a particular idea, their own idea of how life should be organized in their domain. And that’s to distinguish it from the left criticism of critical legal studies, which was demanding, “What are you doing for the working class? What are you doing for racial minorities? What are you doing for women? What are you doing for the poor?” Well, that’s a very good question to ask of anybody. But CLS was not primarily organized with the idea of doing something directly for groups outside the law school. It was, however, totally organized around the idea that reform of legal education in this way would be part of a general left project that was both analogous — other projects to create humane, progressive, egalitarian — but also that we would have an input to the other projects. So the two different ideas, there’s the idea of the milieu itself as a place where a particular vision of egalitarianism and community and solidarity and play very important is being played out among the people who are part of the group. There’s the idea of analogy solidarity with other groups and there’s the hope for input, not in the sense of leading or transforming, but that activities carried on inside the law school could be useful to directly useful to and direct ranges from legal services for the poor delivered by a law faculty. So a very basic idea was the faculty should deliver the services, not pay for them, but deliver them to the idea of producing ideas in academic scholarship that would feed into analogous movements elsewhere, say consumer protection activists or black nationalists or whatever. So the point of acting in your own interest is to get rid of the idea that you think you’re representing the interest of the other. Fundamental to the critique of leftism is the fantasy of leftist intellectuals that their activity is representative of people radically unlike themselves. So this idea is “no, the radical intellectual activities are two: one is the construction of an environment that reflects the ideals. And the second is solidarity, collaboration, and input based on negotiation, because those movements are merely analogous. They can have radically different ideas. And so the input is not like we’re telling you what to do. It’s not like we’re organizing you. The input is how can we collaborate with you? How could our stuff be useful to you?

Craig Orbelian [00:45:49] Professor Kennedy, thanks so much for sharing your insights. I really enjoyed talking with you.

Duncan Kennedy [00:45:55] Thank you for interviewing me. It was a pleasure.

Jon Hanson [00:45:59] Thank you for listening to this episode of the Critical Legal Theory Podcast. This podcast is made possible thanks to our audio engineer Zach Berru and our co-producers Tolu Alegbeleya, Julia Hammond, and Indy Sobol. If you enjoyed the podcast, please subscribe to us wherever you listen and please rate us and leave us a nice review to help us extend our audience.