Ep 8 – Kennedy by Pierce Part Two

Duncan Kennedy [00:00:07] That’s where I’m going to end up is with liberalism is the target, not conservatism. The hegemonic way of thinking is American liberalism. And we didn’t really realize that it was caput until ’81. The target had self-destructed. They’d either destroyed themselves or they’d collapsed, or they’d been beaten up by the right.

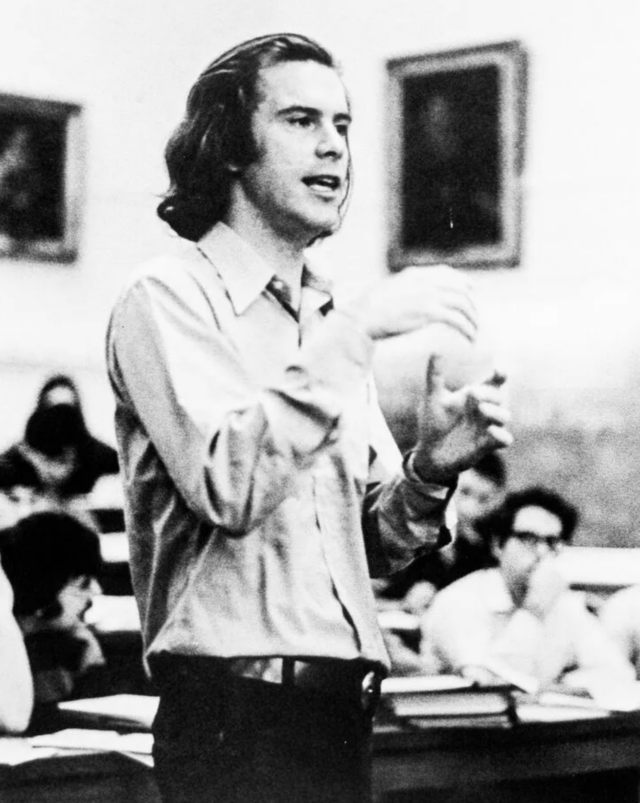

Jon Hanson [00:00:31] Welcome to the Critical Legal Theory podcast, where we hear from legal theorists and practitioners about the ideas that shaped their critical approach to legal theory and law. I’m Jon Hansen, the Alan A. Stone Professor of Law and Director of the Systemic Justice Project at Harvard Law School. In the last episode, you heard the first part of Rio Pierce’s interview with Duncan Kennedy, which examined the personal and cultural history of CLS. This episode contains the second part of that interview. In it, Kennedy delves into his family’s personal history and his own early, formative, educational and professional life experiences. He touches upon topics such as his mother’s commitment to living an upper bohemian lifestyle, especially in contrast with her family’s proud upper middle class background. The impacts of the third and fourth social work movements on his father’s parents’ work as social workers. How his early educational years at Shady Hill and Andover informed his burgeoning curiosities and identity. The role his ideologically complex post-secondary experiences at Harvard College and Yale Law School played in shaping his intellectual development and what it meant to be a Cold War liberal. His perspective on the Vietnam War and avoiding the draft. And his time spent working for the CIA between college and law school. Throughout this episode, you’ll hear Duncan refer to people, events and scholarly works that impacted or interacted with CLS. You can find more information about most of those topics in the links in the show notes on our website. Here’s the interview.

Rio Pierce [00:02:37] Could you elaborate sort of on your grandparents’ background?

Duncan Kennedy [00:02:40] So my mother’s side of the family was upper middle class and was very proud of it’s a very, very, very longstanding upper middle classness – that one of my ancestors was George Washington’s personal physician during the Revolution, and he was the first professor of surgery at the Columbia Medical School then. So doctors run way back in the family. That man is a doctor! And another one of my ancestors was the general who lost the battle of Long Island and was dismissed by Washington for his military incompetence in one of the first agonizing defeats of the revolutionaries by the Prussian redcoats. And they’re very proud of it ever after. So they’re all very preoccupied with that. So, yes, that’s that side was.

Rio Pierce [00:03:32] I’m just sort of curious, how is that? Did your mother tell you these stories as a boy or . . . ?

Duncan Kennedy [00:03:37] My mother was a rebel; so my mother was a bohemian. She loved the stories. But we were brought up to have absolutely no identification of any kind with that. So this is Bohemian, Cosmopolitan, what they called Upper Bohemia. So it’s not a garret in the village. It’s Upper Bohemia, not lower bohemia.

Rio Pierce [00:03:59] What? I mean, if I place a right. She was in her twenties, in the forties.

Duncan Kennedy [00:04:05] No she was in her twenties in the thirties.

Rio Pierce [00:04:07] oh, in the thirties.

Duncan Kennedy [00:04:07] So born in 1913 and she graduated from college in 1935 in the depths of the Depression from Bryn Mawr. So she went to, you know, the ultimate elite preppy college. But her father lost all this money in the crash. So this is a very very important. Many families have these kinds of stories, too. We lost it all in the crash. And then he divorced my grandmother and she took everything he had. And all that was left was enough money to pay for his four children to go to college. So in the later part of his life, he was a lawyer, but he never regained his fortune.

Rio Pierce [00:04:41] You don’t hear much about sort of bohemians in the 1930s, but I guess there has to be.

Duncan Kennedy [00:04:46] But she was bohemian in the third so that, you know, the Bohemian Bohemia begins before the war. So there’s this great movie about John Reed, which describes American Bohemia right before World War One. So Bohemia is totally there from the 1890’s on, and it’s the thirties is a time of the radical development of it. It gets much more political, it gets artists are much more radical and stuff like that. So Bohemia is raging. I mean, in some ways you could say it’s in the fifties it gets normalized from having been a much more powerful upper bohemia becomes more the thing.

Rio Pierce [00:05:20] Is that how she met your father and the those sort of circles in the late 1930, or?

Duncan Kennedy [00:05:25] No, she met my father. She did meet my father in the late 1930s. My grandmother on my mother’s side took her divorced money and moved to Boston. She was very proud of the fact that she did better financially than her husband and she had a kind of salon. And my grandmother on the other side, who was the real bohemian character, she invited her to it because my grandmother taught a writing class. She sustained herself by various things like this writing class for upper middle class ladies who came and did writing. And she critiqued their things for a small amount of money, and she was invited to the salons, took my father and my father met my mother there, and my father was totally antagonized by my mother’s family. So in some sense, she was coerced a little bit into a very polarized . . . She really had trouble with her mother, actually. She really had trouble with her mother. She really didn’t like her mother at all. I spent quite a bit of time with her mother as a kind of offering, so my mother didn’t, if she could avoid it, ever actually hang with her at all. Ever.

Rio Pierce [00:06:30] What what was your grandmother like? As as a I mean, did she was she more proud of the family background? Did she sort of tell the same stories in a different light?

Duncan Kennedy [00:06:39] She did. She she was totally proud of the family background. She was intensely, intensely proud of it. And she was pretty unattractive in many different ways. She was obviously very smart, but this is another thing. So this is the experience that you would find in different forms of the parent who is the alienated situation, the family alienated situation. So we aren’t living like or in relationship to this side of the ancestral line. Now, a large number of crits . . . I’m trying to keep that . . . so I know that we have a conflict of interest to some extent. There is a complicated equivalence there of alienation from the line. The there are the meritocratic, many meritocratic, hierarchical elite crits, had the opposite experience, which is that they were socially mobile, far beyond their parents’ educational income and occupational attainment. So what I’m arguing for is that there’s all these symmetries. So that’s a liberating experience, but it’s also very problematic. This is the same kind of thing. It’s liberating, but we know it’s there. So the question is you don’t relate to it as a matter of integration into your own family system, because the family system is radically contradictory in some way.

Rio Pierce [00:08:02] Did you have any contact with your mother’s father, the lawyer? Was he out of the picture?

Duncan Kennedy [00:08:08] He was out of the picture. He he lived in Buffalo. He died in 1948 or 49, you know, automobile accident. My mother was very closely identified with her father, and she was devastated by his death. And she was then 40 . . . no, she was in her late thirties.

Rio Pierce [00:08:26] And what was your father’s background or . . .

Duncan Kennedy [00:08:29] My father’s background is much more complicated. My father’s parents my father’s parents were when he was born and in the first year of his life, they were social workers, and they lived in South End House, which was . . . you’ve heard of Jane Addams and Hull House and the Chicago Social Work Movement. This is the third or the fourth social movement of the houses. So it’s modeled on Hull House and on the New York One, the name of which I’m blocking, which is so it’s a model in 1900 model of social work. They were permanent staff. That is, they lived in the building which is still there, although it’s long since first it was sold, it was taken by the state. So this is the origins of the American social work system. This is where social work comes from. So he was the research director. He was the protegé of one of the founders. And he, for example, wrote a book called The Zone of Emergence about immigrant communities and Boston and their spatial dispersal from the original slum tenement arrival spots out into the New York suburbs and the further suburbs and all the ethnic complexity that . . . “when do the pols actually, you know, meet the Puerto Ricans, not Puerto Ricans, because there were no Puerto Ricans. But actually it would be the Quebecois would be the really alien.” And then they divorced in the in the mid twenties. And he then moved to Washington, where for the last 25 years of his life, he was when he was in that sort of upper managerial staff of the National Association of Social Workers, not at that time a meritocratic elite job. It’s below that level, so doesn’t pay as much and blah, blah.

Rio Pierce [00:10:16] What was your what was your father’s relationship with with his parents? Did he have a favorite or did he take.

Duncan Kennedy [00:10:22] I spoke to his father once every ten years after his parents got divorced. Their relationship was totally broken and completely antagonistic. He worshiped his mother, lived with his mother, was completely identified with his mother. And when his mother died in 1942, the year I was born again, it’s clearly a watershed event in his life. She, now I have to add one fact. Her name was.

Rio Pierce [00:10:47] Knowles.

Duncan Kennedy [00:10:48] Edith Forbes Knowles then became Edith Forbes Kennedy, when she married my grandfather. She didn’t know her father. Her father never appeared. Her mother lived as a single woman with several other family members all her life. And the family story was clearly Edith was clearly in her own version, illegitimate, and she boasted of that. So this is the bohemian impulse to brag about the fact that you were probably illegitimate. She had a terrible relationship with her mother, who never told anything, anybody, anything about anything. And so she grew up basically with absolutely no money, as did my grandfather, grew up with a little money. He was like the ninth child of a New Jersey manufacturing family. And he escaped and left the family he walks out. So breaks, splits, divisions are everywhere in the story. Everyone is always walking out and never speaking to anyone again forever. And they often did. I mean, this was for real. I mean, anyway, so that’s so they represent the exact opposite strand. There’s absolutely no sense of belonging to either the hereditary or the meritocratic elite. They’re just in a different universe. And so my grandmother, when she went to Paris, sustained herself — this is a basic category of the time — as a lady’s companion to a rich American woman in Paris. So you get to Paris and you she gives you a room in her palatial apartment. And you are like a servant. Except you’re not a servant because you’re more cultivated than a servant. You socialize with her friends and guests, and you take care of many little aspects of business work. She’s a lady’s companion. These backgrounds are radicalizing. So this kind of background, it it’s the experience of extreme social discontinuity, extreme awareness of hierarchy. But you are sitting there in your adequate dress, cheap but adequate dress in the enormous sitting room in Paris, which is just like my other grandmother’s sitting room in Cambridge. Okay. And you are there. And everyone understands that the other women in the room are rich, upper middle class women who are in Paris because they want to be in Paris. And Paris is cool. They’re trying to make friends with some French duchesses, if possible. You are not that. You live in a small bedroom in the back of the apartment. Your children are living in the maid’s quarters and your role is to help in various ways.

Rio Pierce [00:13:29] And so your father so after your father’s mother and your grandfather split up, she went with the children to Paris. How long did your father live in Paris?

Duncan Kennedy [00:13:39] I think he lived there for seven years. He was totally closed mouth about all these things. So it’s very hard to figure out exactly what it was.

Rio Pierce [00:13:47] And you sort of already mentioned this, but this sort of awareness of your family’s fractured history, was did that sort of weigh on your mind when you were sort of in some of these institutions, educational institutions, such as Andover.

Duncan Kennedy [00:14:00] Let’s start with Shady Hill.

Rio Pierce [00:14:00] Or Shady Hill?

Duncan Kennedy [00:14:01] The most basic thing I would say if I try to really speak honestly about what it meant to me would be something like this. So there is a there’s a problem of social facade that is everywhere, which hides and suppresses conflict, contradiction, brutality, death, lust, destruction, romance, ecstasy. These things are actually there. But there is in the 1950s universe, there’s a kind of mythological construction of family life, which I eventually came to see as being a strong resemblance to the 1950s, early sixties construction of political and social life in America. So it’s one set of myths, these myths. And they’re beneath the surface of the myth, things are just really, really different. It’s not that there’s no value. Because there’s all kinds of I actually cherish my family history and it’s a source of pride that they were living hard already in 1905. That’s great. That’s not bad. That’s good. And as between the ones on that side and the other side where my grandfather is going to Harvard Law School graduated exactly at the time that these people were doing social work in the South. And I’m proud of them and I’m proud of the chaos. So it’s not like there’s nothing good. It’s just that there is a kind of mythological construction, which is ideological of a legitimating and deadening of how things are.

Rio Pierce [00:15:40] Was it was the young Duncan able to see the mythological construction as a myth, sort of as a 16 year old?

Duncan Kennedy [00:15:47] Well, 16. You’re getting old, right? 16 year olds are responsible for understanding the world, at least according to me. So by the time I was 16, my parents were divorced and I was okay. I was a big reader. My parents were big readers. I was a big readers. So reading was big. And I was beginning to have that sense. Yeah. And I had at Shady Hill, my teacher in the eighth and ninth grade was a man named Ned Ryerson. And here would be, so let me a would give you a sense of how this works. So Ned Ryerson gave me at a certain point he said “I think you’d be interested in this,” and he gave me a couple of democratic socialist pamphlets written by Huberman and Sweezy. Sweezy was an American Marxist who was fired by Harvard. He was in the Harvard Economics Department, wrote a famous book of Marxist economics about the theory of monopoly capitalism and was denied tenure by the department on the grounds that it was academically valueless. So he gave me these pamphlets. So what was he doing? He was teaching in a Shady Hill school, which was paid nothing. It was a very progressive, elite, progressive school. So very, very elite progressive school paid very, very little. The it was managerial, professional, but also academic children from Cambridge, a lot of people connected to the university. But not only. He taught eighth and ninth grade for like 30 or 40 years and he was a closet socialist. And he basically . . . one of the things he did was he every so often he would pick . . . here’s another basic experience of radicals. So radicals in critical legal studies, it’ll turn out there’s some teacher somewhere back there. My parents were not political radicals. They were liberals. My mother wept when Stevenson lost to Ike kłthe first time she was in tears. She was devastated by Stevenson losing to Ike, but he was not. He was one step more to the left. So basically socialism. And you’ll find this teacher over and over again. There will be this person in the back who sort of identified the future radical, picked him or her out of the crowd of nerds and jocks and sort of says, “hey, kid, have a look at this kid.” And that. Now, he’s however, an example of the story because Ned Ryerson, the word Ryerson. Does the word Ryerson have any you know, it’s an economic historian of the United States. RYERSON what?: steel. Rryerson was one of the three largest steel companies in the founding of American Steel bought by U.S. Steel. Blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. So he was from the plutocratic robber baron elite, and he was part of the rebellion of people in the thirties and forties against their background. So what I’m saying is there . . . the people radicals. So it’s not like there’s a conflict between your elite background and your radicalism. The elite background is what constitutes the context, causes, generates, feeds your radicalism. So he’s taken his independent income, and instead of working for Ryerson Steel and going up through the ranks, he’s become a private elementary school teacher in a very educationally progressive one in the Cambridge, very progressive town — all gown no town community. So that’s it.

Rio Pierce [00:19:08] So what was sort of the environment in your home. With your family you’ve described i think it as “cosmopolitan” in one interview that I saw.

Duncan Kennedy [00:19:16] So cosmopolitan is sort of misleading. It was cosmopolitan, but basically it was upper bohemian. So upper bohemia is designed sort like this: you’re living a middle class, upper middle class life, but you don’t have enough money to do it convincingly. So we lived on the border between Cambridge and Somerville, literally on the Cambridge-Somerville border. So at every moment you’re in a liminal zone here. All of my classmates practically went to camp every summer, but we, me and my brothers, did not go to camp. Why? Because we don’t have enough money. So it’s no beating around the bush. And why don’t we have money? Because we’re artists. So a basic idea here is artists give up money. That’s what you do by being an artist. And you’re if you are incredibly commercially successful, in your art, then you’re no good. Just a priori. Just, you’re no good. If you are commercially successful as an artist, you must have sold out. You must be producing crap. So basically the price of being an artist is not having a lot of money, but you have enough money. So I, me and my brothers, we went to Shady Hill on scholarship. So I had a scholarship and my both scholarships from the four year olds. Before the first grade, we were already on scholarship. Why? Not meritocratic; class solidarity. So the basic idea is progressive institutions cross-subsidize from the prosperous professionals to the people who are upholding the progressive ideals of this sector of the bourgeoisie. So for the first, you know, 11 years of my life, 11 years at Shady Hill, I was the beneficiary of the policy of the school, which loved people like my parents, because they were upholding art and culture. You know, progressively more and more. And my brothers were, too, so we all were. So this is, again, a status, right? Then when I went to Andover, so Andover is the exact opposite — a reactionary institution to its absolute core. And that was a meritocratic scholarship that caused my father to send me to Andover for a year for room, board, and tuition at Andover. It cost him $450 in 1957. Nothing. I mean, just astonishing room, board and tuition. Today, the ticket price of that is $40,000. But that price, like the Andover price at the time, is a cross-subsidy based price. In other words, you cost $40,000. But my granddaughter, who goes to a prep school, pays 20 because it’s the same basic idea. So it’s a cross subsidization for the smart members of the social group who represent, in some complicated sense, a pendant vis a vis money money, which it Andover was filthy, stinking, rich money.

Rio Pierce [00:22:15] How did you guys settle on Andover?

Duncan Kennedy [00:22:17] It was a mistake. Yeah, it was a classic familial mistake. The reason is that Andover had an art an art gallery, which is a very well-known local art gallery collection based on, you know, they’ve been building that for years. And there was a director of the art gallery who was a a bohemian intellectual because he was the art director. And that was the role for the art director. And he was married to a woman who was an artist, who was a friend of my mother’s, who was an artist. We went up and visited. We stayed in his house, which looked just like our house, a more prosperous version of our house. We sat around. It was totally like that. Snookered. I mean, it was, you know, it was not was a combination of Lord of the Flies and Stalag 17.

Rio Pierce [00:23:01] I bet it was great – yeah. [laughter] Did you ever go through a period — perhaps you probably didn’t — but where you were like, “well, actually, maybe I just want to get really wealthy so I don’t have to experience this feeling”? Was that ever a phase or no?

Duncan Kennedy [00:23:16] No. But that’s very common. And, you know, a couple of my close relatives in the extended family of today, their thing, which is like working for the CIA or something like that, is their phase of being obsessed with getting rich. So they all have the same complicated ambiguity and, for them, the thing that’s embarrassing to think about is their wanting to get rich stage. So, you know, it’s always this is, you know, very complicated, but it’s very simple structure. The structure is there’s going to be this thing which has been associated with your rebelliousness forever.

Rio Pierce [00:23:49] Besides the the obviously important pamphlets on democratic socialism, I was wondering sort of what were the other sort of important intellectual influences or books you read and loved and sort of that middle school, high school phase?

Duncan Kennedy [00:24:01] Well, it’s a lot of books, so here would be this sort of atmosphere. So my parents gave me when I was in eighth grade, two books were almost right together. The Communist Manifesto and the God That Failed and then Darkness at Noon. So they both said, “you need to know what communism is. You need to read this. Look, there’s a lot of stuff in here. And then the God that Failed and Darkness at Noon, do you know what they are?

Rio Pierce [00:24:26] I know Darkness at Noon.

Duncan Kennedy [00:24:28] Well the God that Failed is a collection of anti-communist essays. Brilliant. It’s the anti-Communist manifesto of the fifties by liberal intellectuals. Okay, it’s not by right wingers, it’s by liberals. So it’s liberal and communism. And it was basically a pretty overwhelmingly powerful experience. And I totally bought it. And it has not been disconfirmed for me. This 1955, 56, 57 experience wasn’t disconfirmed by studying it. I read from a very early age, I read novels for many years, I read adventure novels. I wrote my first work of fiction, which I abandoned almost immediately, was in maybe the fifth grade, was boy marooned at sea, picked up by merchant brig. You know, one of those things I read a hundred . . . I went to the Cambridge Public Library and I would get out five of them and I would read them and, you know, a couple of nights like that. So it started with that. But I had a very . . . I didn’t have a classic nerd boy experience until Andover because it Shady Hill, everybody was a nerd; and the the ethos was pro nerd. You couldn’t be a successful jock. I mean basically you would be so shamed on a cultural, intellectual level, so brutally that I actually, in the long run, had a lot of sympathy for the people who were good athletes, socially competent, and felt crushed by the school. It was made for the nerds. It was about the nerds, and it was really unfair to the jocks. They were just shit upon. This guy was shat on by an English teacher at Andover day after day, just treated him like dirt, but the culture worshiped him. So this guy was a rebel against the culture. Was fighting the nerd in his class. Why? Because he was an English teacher. So here’s again. Here’s the here’s the way this works for me. This is why I don’t think you can be sectarian. So this is in an English class at Andover, which is a third year english class, junior year English class. The teacher just thinks he’s a combination of an idiot and a vulgarian, and he just visibly loathes his swaggering but also hangdog, because he doesn’t really understand that well. So he’s just being treated like shit. And I felt really sympathetic to it. One of the reasons I felt sympathetic was I could say I was in the same class as I had the sense that what is going on here? So the teacher is not in exactly normal Andover English teacher because he’s clearly totally devoted to literature. But he’s a coach. He’s fully employed as a coach and he’s teaching one class. So he is experiencing he’s an English teacher who works as a coach. What this means is he’s been degraded. So he starts out, he goes to college, he majors in English. He’s a jock, but he’s very good in English. He probably had a master’s in English. He would have liked to be an English teacher in a university. He would have liked to be an English teacher at Andover, but he couldn’t get a job. He was a jock. So they hire him as a coach and they let him teach one English class projective identification. In other words, there’s everything that he regrets, that on some level he is, and he’s rejected. So he’s persecuting the way no nerd teacher would have, because also he has the jock ethos and failing. He’s not putting the Lacrosse ball through the wicket or whatever they call it. [laughter]

Rio Pierce [00:28:06] That’s impressive that you were able ot have that kind of empathy as a teenager.

Duncan Kennedy [00:28:11] No, I had total empathy for him; And it was misplaced. [laughter]

Rio Pierce [00:28:15] So we should probably move on. I guess, unless there was anything specific you want to talk about, sort of creating a nerd identity for yourself at Andover or sort of self-consciously realizing a different place in the status hierarchy.

Duncan Kennedy [00:28:27] Why did you ask?

Rio Pierce [00:28:28] Well, I was just curious.

Duncan Kennedy [00:28:30] It’s a very good question, because in our senior year, there was a group of us who tried to we actually made a kind of complex initiative. So at many schools there were the jokes and the nerds. Some places they were the rocks and the weenies. I think that was in Exeter. At Harvard, it was the rocks and the fairies. So instead of being called nerds, we were called fairies. So that and fairy was a direct homophobic slur on nerds, all nerds are lacking . . . And of course, that’s always totally implicit. Just Andover is a fascist institution, was actually: “why not, you know, call a spade a spade,” so to speak. And so it was the rocks and the fairies. So in the senior year, we created the identity of fairy intellectuals and fairy intellectuals, we defined ourselves as fairy intellectuals in the classic way of the outgroup, embracing the phrase. And we attacked as best we could. We snarked. We sarcastically mocked, and we contested the identity of the jocks who had really been brutal in a very direct persecutorial. It was really a bad place in the first year, which I wasn’t there in the first year. Thank God. Less in the second. But by now the Revenge of the Nerds was approaching because college was imminent and the complex shift that that brought on was beginning to happen. We were being slowly validated and their confidence was being undermined. They knew that they would become they would be in real estate. They would be in commercial banking. Very large number of them ended up in commercial banking, in real estate. And some of the jocks, some of them then went to the Peace Corps because the sixties swept as a wave. And they graduated in 1964 and they were just different people. And then they went off to Kenya for two years, and then they spent the rest of their lives doing good works. The Andover year book, the reunion, so the 50th reunion was weird, so it was just really staggering how the ethical, you know, half of them were just awful 50 years later. But there was this subset of people. It was just really interesting. And religion clearly had a lot to do with it because jock culture, there was something called the God Squad at Andover. So there was compulsory chapel four days a week and an hour on Sunday. So five days a week you had to go to chapel. This is a . . . I was already a seriously fractious atheist. And a big question was, do you kneel? The only people who ever sat up and didn’t kneel were ultra nerds. It’s really because, for the following reasons, this is just fascism. So the minister, in the four years before I got there, was William Sloane Coffin, the leading left Protestant, anti-war, radical left minister. But he’d gone off to Yale, and he’d been replaced by a clod who was very much like the English teacher who persecuted the jocks. He was a jock, an earnest do-gooding, completely thick-skulled jock, and he had deacons. They were called the God Squad, and the deacons were the leading athletes of the school. So the deacons actually would line up in front during the sermon. They would be sitting in the front facing us; the captain of the soc. . . not soccer, because soccer was a nerd sport . . . the captain of the football team, the lacrosse team, the etc. basketball team. And they just it was blatant intimidation. So the basic idea was they were making sure that order . . . he didn’t see it that way. He thought they were the most godly students in the school. These were sadistic little, you know, Mengele pigs who he had somehow managed to interpret. And it was just like a very bad novel. From his point of view, they were cherubic and beautiful.

Rio Pierce [00:32:38] Well, I’m glad to hear there was some student radicalism during your Andover days. I was sort of curious about this. I read that you spent a year in Paris after high school as.

Duncan Kennedy [00:32:48] After I graduated from Andover, I went to Paris.

Rio Pierce [00:32:51] Right. What inspired you to do that and how did that.

Duncan Kennedy [00:32:54] Oh, come on. Who wouldn’t want to go to Paris? [laughter].

Rio Pierce [00:32:57] Well, not everybody has the guts to do that at 18 [laughter]..

Duncan Kennedy [00:33:01] Why did I want to go? Well, . . . [more laughter].

Duncan Kennedy [00:33:08] First of all, it was amazing that my parents let me go. But that was also a function of the upper bohemian style, which was they really treated us as though we were. They didn’t treat us as adults because they were very conscious that we weren’t adults, but they were hyper aware of our relative competencies. And the idea was always, do — they always let us do — much more than anybody else would let us do? Although not anything, it’s a very consistent pattern. So ride a bike early, go where you want. You know, a million things like that. So they let me they didn’t have any money, remember. Now, here’s another confession . . . I may edit a lot of this shit out. So I was able to go to Paris, my parents would let me, I wanted to go to Paris because I wanted adventure. And I worshiped the idea of the art and culture of Europe, although I didn’t know that much about it. I’ve been taking French since the seventh grade. I won the Latin and Greek Prize awarded every year. So in 1960 it was worth $1,000. In 2013 dollars, that would probably be maybe seven or 8000. So it was enough to pay my way over back and forth on a boat. Boat was cheaper than airplane. And to give me enough money so that I could if I could get a job, it wasn’t enough to stay for a year. My parents offered no money. So if, you know: Just come home. And so the job allowed me to stay. And the job was as a bank clerk cashing traveler’s checks in. But then here’s the same experience. Here’s the experience you get. So this is for the Morgan Guaranty Trust of J.P. Morgan’s bank. So what’s the experience? So every morning I get up in my dirt cheap hotel room with a window on the air shaft with a john a mile down the corridor. I get dressed in my little suit, which I only have one suit. I get on the subway, you know, seven in the morning and I arrive at Plaza Vendôme. So once again, because I speak English and French, I cash traveler’s checks at the desk because I’m a perfect person. I was a what’s called a stagiaires, which means a student trainee. And I was paid $120 a month, which was exactly enough to live at the absolute minimum level. Thrilling. I mean, I’m not complaining. It was great where I cash checks for very rich people and tourists. So the two categories were the very . . . At lunch for $0.11, the price of the canteen was $0.11, I sit at a table in a big lunch hall. The table is the same every day, and at the table there were four seats at every table. So but the tables were stable over years. And I was allocated where there was a vacancy and there were three lower middle class French women who did data entry. They were in their thirties and forties, and they were the French petty bourgeois, the lowest of the petty bourgeois French situation, the extreme distance from the people I was cashing the checks for, both from American tourists on the one hand, and from the French upper middle class rich people. And they treated me as a fly on the wall. They didn’t believe that I could speak French or they didn’t really try and they weren’t interested. They had their own life. This was their table. It had been their table for their whole professional lives. They’d been sitting at this table and they discussed their family lives, their personal lives, their children, their husbands, their vacations, hopes for vacations, their parents. And so I would sit there, you know, I only sat there for a fortnight. I would sit there for 35 minutes or 40 minutes. And finally, I actually could understand what they were saying. So it was an unbelievable again, this is that in the class ambiguity. So in this situation, I’m a member of the elite. I’ve already got early admission to Harvard College. On the other hand, between the Ritz and J.P. Morgan. So it’s again, class. It’s very much living on the border between Cambridge and Somerville. To me it was basically the same kind of experience over and over again. So these are basic, fundamental experiences for me.

Rio Pierce [00:37:30] Was this the only sort of service job that you had of that nature?

Duncan Kennedy [00:37:34] No, no, not at all. I mean, my father was an architect and he got me. Well, first of all, the first summer I worked in a factory, so I worked six weeks in a box factory in Kendall Square, which was a plastics factory. I mean, I probably have cancerous stuff floating through my veins, which made plastic cups and plastic sundae dishes and stuff like that. And I was a, we were in the boxers. So that was a factory job which produced some interesting experiences, again, because it was a very bad job for a real working class person. So the working class people who did it were alcoholics like that. But I’m there. And then one of my Shady Hill classmates shows up, having found it by exactly the same route that I had. So this the two of us are there, you know, shining examples of the Cambridge bourgeoisie. We’re boxing. And there’s this woman who is, you know, an alcoholic, single mother in her fifties. Totally disintegrating. I completely found myself identifying with her again in the same pattern. So this is this. I worked to construct two summers. I worked construction. But on small jobs, my father had his favorite contractors. My father designed did rehab, he did . . . he designed houses and built houses. But a lot of his money came from fixing up houses for Cambridge people who were moving into old houses who wanted them repaired because there wasn’t enough work of the new house. He wasn’t very successful in this way, but so I spent two summers working, stripping wallpaper, sanding, carrying hods. They loved making the architect’s son carry a hod. And I really, really liked it. I mean, I can’t say I didn’t like it. It was incredibly for, again, given my attitude, which was this wasn’t unfamiliar to me, this sort of liminal thing was something familiar, and it was a big step up for me in my own experience of myself that I could carry a hod and learn to shingle.

Rio Pierce [00:39:39] So I guess what was your impression of Harvard? Was it was it like Shady Hill? Was it like Andover or was it something in between?

Duncan Kenned [00:39:46] Harvard was in between. It was intellectually fantastic. I mean, it was very ideologically complexly divided and there were . . . it was intellectually fantastic. It was completely an alienated universe. So it had no oppressiveness and zero oppressiveness. Very, very weak internal social connections. The jocks were an isolated minority with their own status hierarchy, but they felt totally marginalized and inferior. They didn’t dominate the culture even slightly, but there wasn’t really and and this was fine with me. So I was come back from Paris. There was no it was the student world was completely disordered. In other words, it was a million groups of two and three and four and five. The prep world existed, the jock world existed. There was various student organizations, but . . . So the contrast was Yale. So this is Harvard versus Yale. We had no feeling that there was any social order that was observing us. So Shady Hill was a completely paternalistic, ultra liberal order with everybody under close observation, and Andover was a fascist order with everybody under close either hierarchical teacher organization or peer monitoring. But so Harvard was freedom. I mean, it was really the big city. It was like living in New York as far as that was concerned. And the faculty were fantastic. So but it was totally alienated. So it was a preview of the Yale Law School. In this way, the teachers had no organized contact with students. There were teaching assistants. They gave their lectures and they were actually hungry for contact. So but the students were totally alienated from the professors in every way. So I, as a good boy and a seducer in an exploiter, would just go to their office hours. And I just had amazing conversations and I developed sort of intellectual relationships with a bunch of Harvard professors. It was tragic. So you go to the office hours and there would be nobody there. Woo. Because it was just, you know, a disintegrated social scene, although in principle and they had to have office hours, they were obliged to have office hours, and it was all . . . like that. So I was influenced by a whole set of teachers who pushed me in the direction, but none of them as much as the Shady Hill teachers. The Shady Hill teachers were more important to my intellectual development than any of the Harvard teachers, like the guy with the socialist pamphlet, but not just him, there were several others as well. So so I’ll just I’ll tell you who the most important professors to me were: the ones who had the biggest impact on me were Edward Benfield, Edwin Benfield, Edward Benfield, a famous right wing, monstrous right winger who is just amazingly smart, fascinating guy who wrote a book called The Unheavenly City. He was the enemy of American Blacks. He wrote a book about the south of Italy as a mafia trust You know, he was really a right winger, really, really, really fantastically interesting person. And he had a devastating critique of the moderate liberalism of the time. And it . . . . was an economist, sociologist critique. It was completely convincing. I loved it. So basically what he said was almost all these liberal programs are obviously self-defeating in various ways, beginning with you’re hurting the people you’re trying to help. But then beyond that, it was also a cultural critique, the precursor of Wilson and of the welfare guy, the guy who wrote the book about how welfare is destroying the family. So he is there direct predecessor. And it was so it was political economy and it was sociology combined in a very, very potent critique of liberalism. [00:43:38]That’s where I’m going to end up, is with liberalism is the target, not conservatism. [5.0s] The hegemonic way of thinking is American liberalism. And we didn’t really realize that it was caput until ’81. It looked like it was going down in ’68, but then it seemed to be hanging on on life support. And only in ’81 did we realize we — we, this generational phenomenon — that, you know, the target had self-destructed. They’d either destroyed themselves or they’d collapsed or they’d been beaten up by the right. So in this period, what’s evolving for people like me is the critique of liberalism. But then I also took some other big influences were a guy named Caves, who was a leading economist person and the name of the antitrust guy who taught a course at Harvard. And it just but was actually in . . . Carl Kaysen. So Kaysen and Caves were two people in the Harvard Economics Department. Caves was an institutionalist I.O. person. He was neo, totally neo classical, but all he was interested in was the institutions, the institutions of the market. He was completely a moderate liberal. He was a centrist in every way. And he was totally unpolitical, but he was totally into you had to learn the critique of what would be Milton Friedman style organizational theory, and Caves was an antitrust person who was a passionate antitruster. So he forced everybody to learn the critique of free-market economics. Caves critiqued the idea that the organizational structure was a free market structure. So these two guys and Benfield, the combination of the two of them was devastating for the liberal consensus about the efficiency of the free market and also the efficacy of liberal reform. So it was very, very good. It was really, really good. And the other people were an anthropologist Elizabeth Colson, who taught a course on African anthropology, which I took in my first semester as a sophomore standing person, having been away for a year, which was unbelievably great. So the anthropological literature that affected everything I’ve done since. Although I didn’t know her, she was just a visitor. She passed through. She was really a crotchety lady, but she was a very good lecturer in a fantastic reading list. Those would be the for sure, the standards.

Rio Pierce [00:46:04] So you took sort of a mainly economics courses and then did you?

Duncan Kennedy [00:46:08] I took the.

Rio Pierce [00:46:09] Anthropology sociology?.

Duncan Kennedy [00:46:11] I took a couple of anthropology courses, a couple of sociology courses, a few history courses. No humanities courses, not one.

Rio Pierce [00:46:19] Just out of curiosity, during this period of time, how robust was the sort of consensus faith in efficient markets during this period?

Duncan Kennedy [00:46:29] That’s a very good question. So this is this is 1962, 63, 64. So Kennedy is now has been elected. And he the basic liberal position is they’re totally for free markets and they’re totally for moderate regulation of free markets. There is a conservative position which says we too are for total free market and all the regulatory stuff is crap. But the Liberal position is very consciously mediating the divide and they’re very, very committed to the analytic. But it’s not just about efficiency, it’s also about growth. So, you know, it’s Walt Rostow. There’s a the against communism, it’s regulated markets. And the market part, because it’s the anticommunist part, is important as the regulation part, which is the anti-Republican or neoliberal part. So they’re right there. They have everything going. And they really believe that it’s a question of judgment. You have to understand that all the institutions have virtues and good judgment is being able to combine them in an optimal way. The trouble with communists is they’re way over on one side. And the trouble with Milton Friedman and the like is they’re way over on the other side. A Sensible person is in the middle. So what Banfield in Caves do respectfully is undermine the idea of the coherence of the position. So neither the market side nor the regulatory side makes that much sense when you look at, in fact, the way these things actually function. And the anthropological thing is even more dramatic because it’s it’s the irrationality of social systems, the a-rationality of social systems. It was really it was just an unbelievably exciting thing. Okay.

Rio Pierce [00:48:07] What was your sort of personal political trajectory during this period of.

Duncan Kennedy [00:48:11] Cold War, liberal So at Andover, I identified myself as and this is actually relevant to a whole bunch of your questions. In Andover and the Andover context, I got off on being a socialist, which was a finger to the whole system, a typical fairy intellectual position with socialism, though, that was, everybody had different pos itions that was not that . . . [laughter]. But and in France, I was really, really affected by the French left. I mean, it had a profound influence on me. The Algerian war was going on at the time and I had quite a bit of exposure to very serious — I didn’t participate — but a really serious political situation in France, which obviously we can’t go into. I still had my anti-communism. Economics. Really, really, really with Banfield and the Harvard Economics Department totally undermined my belief in socialist solutions in the sense of state ownership or total planning. I really. So I was a Cold War liberal, meaning I was for more regulation, land reform in the Global South, redistribution, blah, blah, all those things. But no communism, not even socialist institutional order. So the French telephone system clearly sucked compared to Ma Bell. That proves that socialism doesn’t work. Can’t make a long distance call. You know, it’s ridiculous. It was a ridiculous critique, but totally convincing to me. And anti-communism just as strong. So the basic background idea is that it’s a war between communism and hegemonic liberalism, which is deeply compromised, doesn’t go far enough and really sucks. Stevenson or to the left of Stevenson, not the Kennedys. The Kennedys were sold out. They were nowhere near serious enough about leftism within the liberal progressive paradigm. And then okay. So then from there, here’s how we get to the CIA. So I speak French. I’ve been traveling. I’ve been sitting there in the lunchroom listening to these women, discussing, you know, what to do about their son who is a voyou, meaning a thug. So and travel. I’ve done a lot of traveling on my own and I have a strong sense of the exotic. And that’s how they lured me in. I was more than willing to be lured. So that there was this . . . so wait a minute. So let me just do it this way, because I’m not sure what you want to know about. So the three motives, when I was recruited, I was recruited to be a non-overt — I mean, a covert — part of an organization called the National Student Association. The National Student Association was not a radical organization, quite the contrary. It was a formless association of all student governments in the US. So all student governments could be members of it. Of colleges and universities. So it had 900 or 1000 members, which was only like 30% of all the colleges. And they had there was an annual Congress and they all paid dues. And the dues sustain a national office in Philadelphia. There was a president and a national vice president, an international affairs vice president. The dues were enough to rent in an old building, you know, little rowhouse, Philadelphia rowhouse, and to employ four or five people to do the national organizing work, which was programs that the center offered to the small Catholic Girls School on the one hand, and the University of Pennsylvania Student Senate on the other hand. And then the international thing was foundation funded. So the all the international activities were funded by a foundation which was a CIA fund. So that’s how it worked. The national the international work linked and everybody knew everybody. The presidents and the national affairs vice president would BMOCs. That was part of the cursus honorum for a particular kind of guy. One of the became a Ohio member of United States Congress from Ohio. Another of them actually ran from Congress from Massachusetts. Another and the Ohio guy was actually eventually lost his job because of a corruption scandal. X. So the international thing was funded by this front created by the CIA in the front was created in something like 51 or 52 — in the really intense moment, Cold War, Korean War — as a vehicle to counter the Soviet Union’s worldwide youth and student campaign. The youth and student campaign was designed to convert the youth of the world to the cause of peace. So the first slogan was Peace. The Russians were for peace. The West was for war. And there were a whole series of things and a very deep anxiety in the United States government was that the United States was losing a world ideological war with communism. This is different from, you know, biopower. It’s different from the global military balance. But this is a these are liberals. They’re not conservatives. They’re liberals. And they’re deeply preoccupied with the need to defend the center against fascism and communism. And the ideological battle is key. So here the you know; now here’s the incredible paradox. A major difference between the United States and the Soviet Union is all their organizations of every type. They have no secondary organizations. They have no independent civil society organizations that are all controlled by the state. So a problem for the United States is we want to wage a campaign, so we have to get control of some civil society organizations. To fight their government controlled [laughter] organizations. Oops. It was just deliciously ironic. So they did that. They it was an operation which included funding labor. So big labor, both the CIO and the AFL received massive funding for their international operations, which were building unions and unionization movement in the Global South as free unions to counter Soviet controlled unionism. Because they didn’t have any independent trade unions. A magazine called Encounter, a brilliant, amazing, hyper-intellectual, cosmopolitan, upper Bohemian Transnational magazine, of which the editor was Stephen Spender, a very important English poet. Important English poet. It’s actually pretty good. I like Stephen Spender’s poetry — like that, which was a CIA front. The magazine had no ideological requirements. It was completely. It was left liberalism, anti-communist, anti-fascist, anti-free market left liberalism high culture and just high culture. And the student youth thing. So the foundation funded the international affairs of NSA and also an international organization. There were two international organizations, one Russian controlled and the other basically American and northern European controlled. So they funded these things and then they employed various people like me, who were introduced and we became student leaders. And then we were employed to travel around the world doing the work of student politics in the Cold War, which was organizing meetings, taking positions, figuring out who the student leaders were, were all forming relationships with them all around, and reporting to our CIA case officers who were interested overwhelmingly in two things Who are the leaders of tomorrow? Who are they? We just want to know who are the leaders of tomorrow? Not looking for communists because nobody’s a communist. They’re all nationalists. And then the other thing was, what are the Soviets up to? Anything you can find out about what the Soviets are up to? Now we had our own agenda, which was a Cold War liberal agenda, and NSA had its own foreign policy, which was not the foreign policy of the US government, justified on the grounds that in order to sustain the organization as an American organization, it was democratically constituted. There were annual congresses where we took NSA, took all kinds of very left liberal positions which were acceptable to the CIA because they made us a plausible foreign front. So we went around and denounced many aspects of U.S. foreign policy, which was totally cool. It was just one paradox rolled into another. So I did that for a year, and then for a year I worked in Langley, inside the agency, in the section of the agency that managed these operations. So that was an inside desk job. Why did it do it? I did it for three reasons. The first reason why I did it was to get out of the draft. That was a very straightforward, you know, Vietnam. Basically what happened was I got married. The draft accelerated. They took away that married. They withdrew the married exemption from the draft. A month before we got married. “Call off the wedding!” No. [laughter] So that was one reason. You know, getting out of the draft was a really serious concern. And it was a big issue. I mean, people like me wanted to get out of the draft.

Rio Pierce [00:57:57] This was ’64, ’65?

Duncan Kennedy [00:57:59] It was 65, 66. And it was amazing. I mean, it was just taking off. The war was taking off, land seriously. There were now 200,000 troops maybe. And we were beginning to hear about what it was like, which was, again, people you have to do, you have to . . . Do you know what a first lieutenant is? Well, the first and second lieutenants in Vietnam were us. They were college educated draftees, Ehh! And the highest casualty rate was second lieutenants. They were the people who were actually being killed. So I was afraid of dying in Vietnam. I actually had a fear of death, which was probably fairly rational, although it’s almost certainly the case that I could have found some way out of it. And I also really didn’t want to delay my career by two years. And I was married, didn’t have a child, but was married.

Rio Pierce [00:58:59] Now were you . . .

Duncan Kennedy [00:59:00] The third thing was travel. So wait a minute, did I have a second . . . So there was Vietnam, there was travel, and then there was anti-communism. So so I had some I, I didn’t do it in order to fight communism. But my basic background idea was that the Cold War liberal position, which is you have to break some rules because they break rules, was true. Now, in this case, I think it wasn’t a good call, but I don’t disavow that basic background idea because I’m not a liberal legalist. So I thought it was, and I still think it’s justifiable sometimes when the stakes are big enough, the end just plain justifies the means, even if the means are immoral and horrible. And sometimes you have to do it and you’re a jerk if you won’t do it. Someone else will do it or the bad consequences will flow. But I don’t think it was a good call.

Rio Pierce [00:59:53] Joining the CIA or.

Duncan Kennedy [00:59:54] The operation.

Rio Pierce [00:59:55] The overall CIA operation.

Duncan Kennedy [00:59:58] It was great for me. And I didn’t do anything about which I feel intensely guilty, fortunately, and by accident, in other words, that I could easily have. And the fact that I didn’t is not a testament to my moral fiber or my discernment. It was luck, basically. Now, back against this background is not going to Mississippi. Not going to Mississippi is as important as this. So in my senior year at Harvard, a very good friend of mine, a woman who was in Shady Hill, who I’d known since I was four, who is a real friend of mine from childhood, said to me, “Hey, I’m going to Mississippi. It’s Mississippi, Summer. You should come, too.” She knew that I was totally sympathetic to it. She knew and I thought two, three things: too dangerous. It’s like going to Vietnam. I mean, it was really dangerous. Yikes! Second, what about my career? I mean, this is gonna commit me against the mainstream liberalism who really don’t like the civil rights movement in its more militant violence-provoking form.

Duncan Kennedy [01:01:07] Was this before the 64 Civil Rights Act or right after this?

Duncan Kennedy [01:01:11] It’s exactly at the moment. The Civil Rights Act is being passed in response to the beginning of these activities. And these activities are understood to be radical things, very strongly influenced by all kinds of American radicalism that are incompatible with the ethos of the liberal hegemonic establishment, which does things like the Civil Rights Act to respond to them. So the person who’s getting attacked by the dog is not an inside liberal hegemonic person. That person looks at the white meritocratic elite person being attacked by the dog and responds by the Civil Rights Act. But the person being attacked by the dog is not destined to be the person who enacts the next Civil Rights Act in this model. They have a functional outsider status. They’ve shown bad judgment, among other things, by doing this. So I said “no,” and I didn’t have any hesitation about saying no. I didn’t. I thought it was dangerous. I thought it was completely virtuous and completely the right thing to do. But it was also didn’t correspond to my career plans.

Rio Pierce [01:02:18] So at this at this point, you had a it seems like a very strong self-conception of yourself as a future wielder of state power. I mean, that was sort of a Cold War liberal, a married man, CIA. Did you have a dream?

Duncan Kennedy [01:02:31] That’s exactly right.

Rio Pierce [01:02:32] A dream of a future Duncan – some undersecretary of some government.

Duncan Kennedy [01:02:37] Why undersecretary? What are you talking about?

Rio Pierce [01:02:38] Secretary!

Duncan Kennedy [01:02:40] Come on! Don’t sell me short for Christ’s sake. [laughter]

Rio Pierce [01:02:41] Director. Chief.

Duncan Kennedy [01:02:44] Well, this is too early to be, that is, sensible participants in this system. Again, this is an important thing to understand about it. We all understand that it’s completely a gamble. There are very large and under secretary might be great might not make under secretary. The basic idea is you have to have something to do when your administration is out of power. If you’re a Democrat, you have to do something when Republicans are in power and vice versa. There are very large number of careers in the elite. Those are just some of them. And of course, you know, it’s extremely unlikely that you will be any of those things. But there are millions and millions of things that seem plausible. And then there’s the idea that you’ll be politically engaged. But this idea is not state power for its own sake. It’s state power for liberal, progressive, Cold War, liberal ends. So the background commitment is poverty, race, not gender, because that’s not part of the story yet in any big way. It’s basically redistribution. And racial justice, which are the liberal Democratic good part of the Liberal Democratic Party, which is frustrated by the fact that it’s dominated by conservative Democrats and the Republicans are some of them are liberals. The idea is we need to break through, which would have been someone like Stevenson. And the point about the Kennedys is they’re not going to do that. They’re too linked in. So the state power idea is people like us, and it’s a collective generational thing, will achieve state power, will be dispersed among the many different jobs and functions. No one of us has got a guarantee of anything. But it’s a collective project. It’s not an individual project.

Rio Pierce [01:04:22] Now, at this point, you obviously, you had differences with the Kennedys. What did you think of the Warren Court to the extent that you consciously thought about it during that college, during the college years, at least.

Duncan Kennedy [01:04:34] Didn’t really . . . . Well, there’s Brown versus Board of Education. Then there were good Warren Court decisions. What the newspaper shows you as liberal Warren Court decisions. And so I was very sympathetic to the Warren Court. I thought it was great. But I didn’t know anything about it. So really nothing. The Warren Court is not yet politicized quite in . . . The people who hate it are the Southern Democrats – who are the main opponents. . . .The Republican Party is dominated by liberal Republicans who appointed . . . Eisenhower appointed the Warren Court. So it’s almost all of them are Eisenhower appointees. So the Republican Party is not polarized against the Warren Court yet in this period.

Rio Pierce [01:05:19] So when you were graduating from college, were there other alternatives besides the CIA? Had law schools started to enter the picture yet?

Duncan Kennedy [01:05:26] I never thought I was going to do the CIA for more than what was required to get out of the draft.

Rio Pierce [01:05:29] Right.

Duncan Kennedy [01:05:30] Go out of the draft, I said.

Rio Pierce [01:05:31] Besides that, did you have . . .

Duncan Kennedy [01:05:33] So I never planned for a minute to stay in the CIA? And when I got there, then I had my political my political transition occurred while I was there. That made it even I mean, I never intended to stay anyway, but that also gave me a kind of free hand in my own experience of it that I wouldn’t have had if I wanted to stay.

Rio Pierce [01:05:49] When did you start thinking about going to law school, or was that an alternative when you were graduating?

Duncan Kennedy [01:05:53] Yeah, that was an alternative from the beginning because the most basic thing that people like this did was you work at a Wall Street law firm and then you go to the government, and then you come back . . . . So I totally understood that that was a career model, and that was my model.

Rio Pierce [01:06:07] The more things change, the more they stay the same.

Duncan Kennedy [01:06:09] So I applied to law school, you know, in the beginning of my second year working with the CIA I applied to Law School. I only applied to Yale because Harvard was the right wing law school the way I understood it, although Harvard thought it was liberal. People like me thought it was a right reactionary culturally and also politically reactionary. And Yale was a left wing law school the way we understood it.

Rio Pierce [01:06:30] How conscious? Had you read legal theory, legal process stuff? At that point?

Duncan Kennedy [01:06:35] No.

Rio Pierce [01:06:35] You didn’t know much about the law. You were still coming from it, but you were able to find out.

Duncan Kennedy [01:06:41] No. I knew about this much about law: when I was writing my undergraduate thesis. My thesis was the topic of the thesis was economic dominance in the colonial relation. So it was an attempt to do a left wing economic analysis of colonialism and how colonialism . . . The idea was to interpret colonialism as an exploitative economic system without using Marx’s category of exploitation based on the labor theory of value. And I had the insight that the only way to do that, it had to have something to do with law, because otherwise it was just a free market. So there had to be something going on. And so I spent a lot of time trying to figure out the legal system of Nigeria, and it just couldn’t be figured out. I mean, I went to the library, I asked I came to the Harvard Law School Library into the law school library in Langdell. I went to the reference desk. I said, “I would like to get the laws of Nigeria.” And she looked at me and said, “Nigeria is not a code country. There’s a common law country. The laws of Nigeria don’t exist in that form.” Hmmm. A problem. Insoluble problem. She didn’t have any suggestions, so I realized I couldn’t find out what the laws of Nigeria were because they weren’t written in any codified form. So it was like that. So I knew there was a law problem. My dissertation was about how the rules of the game of colonialism were stacked against the colonized. That was what it was about. And I knew law was part of the rules of the game, but I didn’t know the first thing about it.

Rio Pierce [01:08:18] Were you initially supportive of the Vietnam War as a Cold War liberal or did you?

Duncan Kennedy [01:08:22] I was on the fence for a very short time on general principles that you should not prejudge these things. But I mean, it was just was very it didn’t take any of us very long. So already by the time I went to the CIA, I was already totally against the war.

Rio Pierce [01:08:38] Well, I guess you were. Did you meet your wife in college or you?

Duncan Kennedy [01:08:42] I met my wife in college, and we got married the year after I graduated from college. I had a enormous health problem as a result of my travels, so I was basically incapacitated more or less for a year. That’s when I went to economics graduate school for a semester, which I dropped out of because at that moment, econometrics was taking over and it was obvious that I couldn’t pursue a successful career as an economist if I didn’t have enough. I didn’t have enough math and I didn’t want to get it. I was I thought I have other capacities, so it’s a waste to go down that route. Although I wasn’t math phobic, I knew I couldn’t teach myself. So and so we got married in that year and then went.

Rio Pierce [01:09:24] What health problem did you have?

Duncan Kennedy [01:09:25] Traveling on one of these — actually this was a CIA funded trip before I knew about that CIA had anything to do with it.

Rio Pierce [01:09:32] These were during your summers at Harvard?

Duncan Kennedy [01:09:33] Yeah. No, it’s actually was this one was in a winter. But in Indonesia, almost certainly because this was rampant at the time, I was a risk-taking traveler. I ate the native food, blah, blah, blah. All these things drank the water. I developed an amoebic ??, which is a very serious tropical illness. And they attacked my liver and I sort of went into a coma. I had eventually a massive operation. When I got to the doctor’s office after I was in the hospital for like three weeks in intensive care for ten days, I got to the doctor’s office in the nurse who is at the desk said. “Wow, it’s so great to see you.” I said, “Wow, I’m glad to see you’re so happy to see me.” And she said, “Well, you know, you almost didn’t make it.” And I said, “Well, what do you mean?” She said, “Well, the what we were saying was it was a 20% chance that you would die, not that you would survive, but a 20% chance that you would die.” So a very significant chance. And that incapacitated me from doing anything active and also got me out of the draft medically out of the draft for a while. We went together to Paris and then went together to Washington and then we went together of to law school. First child was born in the second year working for the CIA right after applying.

Rio Pierce [01:10:43] And she had she’s a creative writer, which she sort of.

Duncan Kennedy [01:10:46] She’s basically does a couple of different things. She’s a therapist, she’s a family and a couple therapist, basically. And she teaches therapy, basically kinds of stuff at Cambridge College in Cambridge. And she also teaches; she writes for a magazine called The Improper Bostonian every other week column. And she also teaches a couple of classes on writing from your own experience, exactly what my grandmother taught, really astonishing.

Rio Pierce [01:11:16] Did she encourage you to sort of go back to some of the sort of the English, the writing, the fiction writing stuff since you hadn’t done any of that in college or was that.

Duncan Kennedy [01:11:25] No no. I would say I had. No. That’s that’s an autonomous, very powerful long run interest, which began when I was a kid. So I’ve been doing basically the literary side was always there, but I didn’t do any. I started doing it again when we went to Paris. I didn’t do any write any fiction after. When I was at Andover, I wrote a whole bunch, but then I didn’t do any more in the three years in college.

Rio Pierce [01:11:53] Sort of what you were saying, getting married at 22, 23, an example of the sort of fifties mentality stretching into the mid-sixties idea of how families operate.

Duncan Kennedy [01:12:02] Totally. That’s absolutely true. And nobody else got married. I mean, we were on the cusp of the transition, just exactly on the cusp. So but everybody got divorced between 1978 and 1982. Virtually every couple that we knew, they all got married in the later sixties and they all got divorced between 70 and 82. It was an amazing, just astonishing, culturally uniform thing.

Rio Pierce [01:12:27] I think we’re out of time. All right. Great. Thank you so much.

Jon Hanson [01:12:33] Thank you for listening to this episode of the Critical Legal Theory podcast. In the next episode, we’ll hear part one of Craig Orbellian’s interview with Duncan Kennedy, where they discuss Kennedy’s essay “Legal Education and the Reproduction of Hierarchy A Polemic Against the System.” This podcast is made possible thanks to our audio engineer Zach Berru, and our co-producers Tolu Alegbeleye, Julia Hammond and Indy Sobol. If you’re enjoying the podcast, please subscribe to us wherever you listen. And please rate us and leave us a nice review to help us extend our audience. Thanks.