Ep 6 – Kennedy by Marr Part Three

Duncan Kennedy [00:00:08] And there’s a certain moment when one of the women participants said, “look, the women have to meet.” Some guys are offended. They’re just offended. Whatever happened to CLS? What destroyed the movement? Why didn’t it survive? It’s so difficult to get a movement started that it doesn’t make any sense to pay a lot of attention to how it ended. [24.5s]

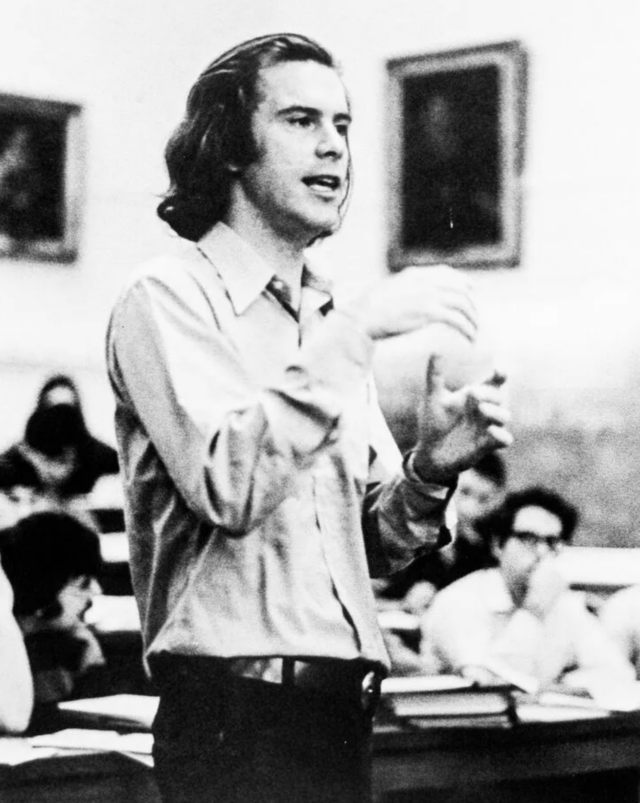

Jon Hanson [00:00:33] Welcome to Episode Six of the Critical Legal Theory Podcast. I’m Jon Hanson, the Alan Stone Professor of Law and Director of the Systemic Justice Project at Harvard Law School. This episode is the final segment of Abby Marr’s interview of professor Duncan Kennedy. In this part, Abby and Duncan expand upon their discussion of the role of identity, gender and hierarchy within CLS and other social movements. They also returned to the topic of how critical legal studies ended as a movement and explore the lasting impact of CLS on legal education and leftist impulses in 21st century legal academia. Throughout this episode, you’ll hear Duncan refer to people, events and scholarly works that impacted or interacted with CLS. You can find more information about most of those topics in the links in the show notes on our website. Here’s the interview.

Abby Marr [00:01:38] My first thought and reading “Psycho-Social CLS” was that just the role of desire in really shaping and forming who got involved and how the movement developed. And I was wondering your thoughts on that because that was the undercurrent.

Duncan Kennedy [00:01:51] So the background of that is crudely Freudian. So I’m very influenced by Freud, though not the Oedipus complex, but the basic background, what you might call Freud’s energetics, which is the idea that instinct transformed into erotic and also aggressive and destructive affect is a fundamental driver of everything. So many highly sublimated, very intellectual activities can only be understood as having some drive of desire behind them. So desire doesn’t, in that sense, mean the desire to have sexual contact. But of course, there’s no sharp division. So it’s very important to this way of thinking about it that there just isn’t a radical separation in interpersonal relations between interests that are understood as neutralized and interests that are much more concretely erotic. And the charismatic speaker is the famous example of this. Freud is not the only one everyone really understands is a strong there’s a strong eroticized element of almost all performance. Performance runs partly on that energy, the way it’s communicated back and forth. Social movements are hotbeds of desire, partly because of their self-conscious stepping apart from the conventions of the overall system in society. They’re capsules. They get people in the a general high level of affect. So in other words, they’re excited. So without saying it’s not sex, it’s just excitement. So it’s intense. And that’s itself: desire breeds desire. Excitement breeds excitement. So that dimension of it is everywhere, but also the repression of it. So the and again, we don’t want to be free for I mean, both the desire and the repression are artifacts or culturally conditioned things. But in this form of late seventies, early eighties, there’s a much before the arrival of the the version of feminism preoccupied with danger in the pleasure danger thing. There is a it’s quite a sort of loosely sexy atmosphere, but it’s very quickly, quickly shut down as the feminist analytics in the culture of the radical feminist minds of the extreme danger to women, that desire is harnessed in the interest of domination. So the eroticization of domination thesis becomes a central dimension of the way everyone understands mentor mentee relationships. It’s almost the perfect example. It’s like sexual harassment in the workplace. So the basic idea is the boss harasses the secretary, and that’s partly possible because of the eroticism. The secretary falls for the eroticization of the dominant relationship, and that’s, for me, MacKinnon’s single most basic and most brilliant insight. It’s the thing where MacKinnon, just. For Dworkin, it’s principles are part of the legal order. For MacKinnon You have to have the eroticization of domination as part of your theory of gender hierarchy in the system. So what about that? Well, in any real social movement, this is going to be a problem. But here we have the structure, which is the women are arriving after the men. And the you know, there are very few tenured women in the original as CLS emerges from the late seventies into the 80s. Remember, it’s all going to be over by 1990. So it’s all 1991. So it’s not this is not a 30 year process. You can sort of identify the waves of people as they arrive. So they’re . . . But then the truth of the matter is that the Oedipal bond of the guys with their mentors is just as powerful and just as tortured. So it’s really a mistake, the the focus on heterosexual, the eroticization of heterosexual emotion. It’s really true. And you really have to. But it’s just not qualitatively different from the, you know, the guy who was going to Harvard Law School and written his third year paper and taken every class that Morty Horwitz taught and then gets his job, because Morty Horwitz, they’re not going to fuck, but almost nobody’s fucking. I mean, the mentors and mentees are not doing a lot of that. Though, it’s also true that if you look at the older generation of white men in critical legal studies, a surprisingly number of them are married to, didn’t divorce, got married to it, stayed married to women who they first met as their students. Another wrinkle: how are we to understand that kind of thing? So this is not affairs between teachers and students. It’s marriage. And it’s like five of the most senior people, just like five of them are half Jewish and half not Jewish. And four or more of them are defined by their intense relationships with their more cultivated mothers and less cultivated fathers. It’s another basic structure of this universe. And, you know, it’s hard to discredit the marriages given that there are 20 years old and the people seem to be highly mature, you know, and admirably, whatever. So all of these things, then you add the gay and queer dimension, which comes along at the as a reaction against the danger and not pleasure, eroticization of domination as purely bad and at the same moment of the feminist rebellion against the de-eroticization of domination. So this is I don’t know if you know, this sort of side of it. It’s so this is lesbian S&M. It’s a very explicit rejection of the constructions of female, of female sexuality, not male sexuality of MacKinnon and also of Robin. The Robin is not the same as MacKinnon. I mean, cultural feminism and radical feminism are really were different in this respect in many respects. So what happens is this generational thing. What I would say is it adds to the explosive mix, which I’ve described as having all these other dimensions. It’s not the thing, but it’s part of it. And any attempt to build a social movement, again, I think everything that I’ve been describing is everywhere in all social movements and that. I think the history of social movements, serious sexual abuse by male charismatic leaders, of large numbers of women subordinates in the movement has been a big issue. I don’t think that was true in critical legal studies, but by the way, that doesn’t mean nothing bad ever happened. And also, I do believe that the that are just as important. I mean, the phenomenon of the role-reversed guy was a very important phenomenon in CLS had a big influence on the unfolding of the movement.

Abby Marr [00:09:08] And what did that look like concretely? Do you have an example?

Duncan Kennedy [00:09:11] So I’m just going to tell you an anecdote so of CLS gender politics. So at a summer camp that happened in Windsor, Ontario, which was a summer camp which was just close to evenly men and women, a lot of it’s just the moment when all these things are arriving. So there were probably 30 people there, 15 men, 15 women. And the basic program is reading the various theoretical stuff, but then articles by the people, it’s very intense. And then race, gender and class are always sort of present as subtexts in CLS kind of stuff. And there’s a certain moment when one of the women participants said, look, the women have to meet. Their are gender issues here and we just got to talk about them. It’s ridiculous. And she elaborately said, it’s not against you guys at all. This is nothing. Really, it’s completely just we need to meet. I mean, just it’s crazy to say we can’t meet because we are an integrated group. That’s crazy. That’s crazy. If some guys are offended, they’re just offended and other guys are totally, totally on board. So as a as a gesture, which still amuses me, just I said, “well, I think the guy should be, too.” Now this produced a fascinating reaction. So a bunch of guys. “Absolutely not. We are not going to collaborate with the reduction of our politics to identity politics. We don’t agree with them meeting, and so we certainly should not meet ourselves. There are 15 guys. So that’s five guys there. There are five guys who say, “wait a minute, it would be an act of incredible, aggressive hierarchical domination for us to meet. The whole point about this is we shouldn’t meet. We need to wait and see what they have to say.” And then there were five guys and we had a meeting, the only five of the 15. And, you know, it was an empty space. And we sat down and we had a very good time. I have to admit it was very amusing. We urged the other two groups of five to meet as rump caucuses and they refused. So, okay, that’s a story. It’s more complicated. That’s a complicated story for the way the guys were in relationship to it.

Abby Marr [00:11:29] So I keep going back to this, but I want to go back to hierarchy again. This is an anti-hierarchical movement we’re discussing. And yet you’ve talked about all these complicating factors coming in. In mentor-mentee relationships, in building a multigenerational movement, what were things you did to address hierarchies and other complications?

Duncan Kennedy [00:11:47] So first of all, there’s an element, I mean the mentor-mentee relationship has an element of hierarchy. I mean, there’s obviously that’s very. Yeah. So the question is, how do you deal with it? The question is not you can’t get rid of it. The question is how you deal with it. And I don’t think I mean, I don’t think I have a lot to contribute that isn’t sort of common sense or obvious. So a very basic issue is intellectual autonomy in a situation of intellectual influence. So you can’t have the attitude “it sure would be great for you to enrich, develop and strengthen my ideas.” No, you’ve got to have some real desire. So this is where this is a desire issue also. So there’s the desire to swallow and there’s the desire not to swallow. But to be confronted by the other as an exciting other object. So very basic question is in relation to the mentee’s work. Do you want to incorporate it? Do you want to make the mentee part of yourself and your project or do you look forward to want to be challenged, batted back? It doesn’t mean you’re not going to be loved. So a lot depends on your model of love. So a very basic division in the way people manage these relationships is whether you like the Eros of conflict across generations or whether you hate it. And that’s true for the mentee in relation to the mentor as well. So for me that’s a very deep connection between the issue of hierarchy and the psychological dynamic of love or Eros or desire energy, whether the other as other is more attractive or less attractive than the other as incorporated. Pretty abstract.

Abby Marr [00:13:41] Yes. Do you. Do you have other ways in which you thought about that in a more concrete way, on the mentor-mentee relationship you’d like to share? If not, that’s fine.

Duncan Kennedy [00:13:51] Well, that is, you want your students to produce stuff that’s sufficiently different and not too different. I mean, come on. But sufficiently different. So that’s the first thing. So then the second thing is, how do you deal with their their hierarchical desires? So basically their hierarchy of disaster deserves to succeed. So again, here, it’s important to identify with their desire to succeed independently of you. This is different from their work being different from your work. So a basic question is do you support them in their upward struggles, even if their upward struggles have nothing to do with your project? So it’s a model, a different kind of a model than the model of. And I would say that’s hard. I mean, I often become less interested in the work of my mentees when it’s no longer related in some way to the Critical Legal Studies Project. That’s when I would say I am only partially successful. I just tend to lose interest if it’s not part of the same thing. But then also the micro levels of interaction. So Joe Singer suggested to me a very good moment. He said, Here’s something you can do, that he was a student, I think, or he was a very junior professor. He said, “Just turn your desk around so that you’re not confronting the student across the desk.” The desk is on the wall. When the student comes in, you turn your chair and you are then in the same room with the student. So you eliminate the desk as barrier. And if you go around Harvard Law School offices today, there really are two office furniture arrangements in one of which you’re across the desk from the teacher and the other, which you’re not. And you can immediately see it has psychological meaning, though of course it’s manipulable in all directions. Some very hierarchical guys have mastered, etc., etc., etc.. And so very, very nice and collegial learning. People are clearly want that barrier because they’re so vulnerable to being engulfed that they want to keep it between them. So.

Abby Marr [00:15:51] Again in the interest of time, then I just sort of want to fast forward to the end of the movement and looking back on the movement and what lessons you can draw from those personalities and relationships. Looking at now, any sort of following movements, any successor movements that might . . .

Duncan Kennedy [00:16:10] Pause. I guess my first reaction to that is the end of the movement. It’s so difficult to get a movement started that it doesn’t make any sense to pay a lot of attention to how it ended. But it’s inevitable that people thinking about starting a movement, they’re thinking about lessons. What are the lessons? Whatever happened to CLS? What destroyed the movement? Why didn’t it survive? So my basic reaction to that is, at this level, I’ve just described how it came to an end. That is it’s a combination of factors like, you know, there’s a lot of factors, right. Producing a kind of firestorm of internal intensity. And then this moment, that’s very typical, as I’ve said. So what are the lessons of it? The lessons of that is you’re lucky if you participate in such an experience, from my point of view, and it’s certainly not the case that you can figure out how to avoid them if you wanted to. The question of how to start a movement is more actually accessible, I think. I think there’s more to be learned from CLS about how to put them together than there is about the other. And the very basic aspect of it is the idea that you get started when people who have social connections identify grouplets that are not in touch with each other except through this person to the and then they come together. So in the in the in the occupation of Bob clerk’s office to try to get Regina Austin a job, there were three students who participated in the bureau, the Jamaica Plain thing, the National Lawyers Guild. One of them was in the Women’s Law Association, which was totally not involved as an organization. There was a BLSA person. They actually it wasn’t the organizations. It was in each organization, there were three or four or five people, and they didn’t know each other. And these people put them together as a coalition for this action. And that created a new social dynamic because the people then connected across . . . . The CLS thing is exactly the same. I forgot to mention the Buffalo component. So there was a Wisconsin component and a Buffalo component. The Buffalo were for people who and the name is Al Katz, Bob Gordon, and Jack Schlegel were all teaching at Buffalo. So those people, they didn’t all come, but they were clearly another one. And Trubek didn’t know them, but I did. And then he got them hired. Two of them got hired at Wisconsin, creating a new Wisconsin thing. So this thing, which is the movement, doesn’t start with a clarion call to which people flock. At all. It starts as preexisting grouplets that are put together in a larger group, and then recruitment is a really different operation from this initial thing. And recruitment really requires some kind of model of who the audience is. So when people in the Harvard Law School student body, when leftists or the Unbound people, whatever, talk about CLS, I’m never quite sure with what they’re talking about. So are they talking about a faculty movement? They’re not going to be here unless they become law professors. Students who are part of the initial CLS moment then went off in to the rest of their lives. Public interest law, a lot of them or legal services a lot of them were just law practice or they went they dropped out of law altogether. The organization, the CLS movement was a movement of law professors. And so the recruitment technique was about law professors. It was how do you get . . . so the student, the students who were recruited had it communicated to them that this was a route to becoming a law professor of a particular kind? When would be so? When? So let me ask you, the interviewer, when you think about lessons of this for another CLS movement, what are you imagining? I don’t think you’re probably imagining a movement of law professors. Or maybe you are.

Abby Marr [00:20:25] I think I’m imagining a couple of things. One would be a movement of law professors in what you see as sort of the successor movements that have come about. Well, theories that have come about the further development of feminist legal theory or not, the further development of queer theory, critical race theory that’s still being written about and talked about. (Yeah.) So an organizing component to that, what that would look like or how that could come about. And then also sort of a movement inside the law schools, but about students and professors . . . two things.

Duncan Kennedy [00:20:54] Right, so that so those two things are really different. The first so at Harvard Law School now there are seven or eight professors who are unmistakably crits, though you might not know that if you look at what they write and their preoccupations, they are part of a successor thing. They aren’t very interconnected with each other. So in fact, they barely know each other. Most of them, though, I know all of them. And then there’s a couple of other people know more than one. But for you as a student, it’s nothing easier than to hook up with people. So Janet Halley is totally blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, but Janet Halley has an ambivalent theoretical relationship to Betsy’s version of Betsy Bartholet’s version of feminism, which is true liberal feminism, that is liberal feminism, serious liberal feminism. In fact, the gender politics of the women members of the faculty and of the small number of guys who are interested in gender politics are completely complicated enough to keep, you know, what is the relationship between Diane Rosenfeld and blah, blah, blah? So, you know, you don’t need a new critical legal studies movement as a student to participate in a really vital gender discussion. Unbound aspires to be the second thing that you’re talking about, but Unbound, clearly. I love Unbound. I’m to. . . I was one of the original sponsors of Unbound, and I see it as partly a faculty-student collaborative effort, as do several other members of the faculty. By the way, the international thing is even more intense than the gender thing. So a student-faculty thing that would be have some of the qualities of the better moments of student faculty collaboration, both mentor mentee and also broader based student activism and broader based faculty activism would be fantastic, and that is something that doesn’t exist, we can imagine existing, and all the things I’ve talked about are relevant to that. As long as we’re not talking about CLS in the form of the law professor and legal academic thing. A basic problem here is what is the current left student critique of legal academia? I knew what it was because I was a student, you know. But it’s very unclear today to me what the left’s critique of legal academia is or their law school experience. Very unclear. I know that there is one on many levels. I don’t understand the race and gender dimensions of it, the class dimensions of it. I don’t understand what the current sort of I used to have an intuitive sense of that, partly because it was you could sort of see in various ways class dynamics playing out. But now your generation is very, very, very expertly disguises class indicia, unless they’re deliberate. So some Marxist working class guys come into the office and they tell you by their clothes, you know, they look that they are Marxists, working-class guys, but that’s rare. In general everybody looks exactly the same. Not exactly the same. Sorry, a million differences, but they aren’t this difference.

Abby Marr [00:23:59] As a professor, having been here a long time, do you see that the crits changes Harvard and then legal academia for you, or do you see it as sort of the same?

Duncan Kennedy [00:24:11] I think we as a part of a general phenomenon, so it’s impossible to take out how much is we from the more general generational and political change, but massive change. And much of the change is directly, I think, attributable to critical legal studies. Know this is only partly ironic. Maybe the single most important attack on hierarchy in legal education that critical legal studies accomplished is getting rid of Harvard’s number one hegemonic status in the system. So an unbelievably important aspect of American education was Harvard’s just unquestioned dominance. Yale constantly running to “We really are better, but nobody recognizes it.”So critical legal studies created a gigantic series of scandals which persuaded the deans of all other law schools that, as a matter of fact, the time had come to take these fuckers down, and they did. And it’s great that they did. So . . . also students were really discontented. We fomented so much student discontent. It was great and all the conflict made students unhappy. So the combination of the deans horrified by the faculty conflict and students enraged by the fact that everything was hysterical, we became number three. Yes! If you want legal education in America to be less pronounced disgusting and horrible, that was just a great event. It pluralized the system in a new, really, really new way. We had an effect. So when two thirds of the students in the first year class have been rejected by the Yale Law School, progress has occurred. Harvard is a better place as a result. It’s really, really a good change. Terrible for Yale. And it’s just a disaster for Yale, but it’s great for us. And if that ended, if Elena Kagan had managed to end that. It would have been a disaster for Harvard. So next: classroom style, I mean, the classroom. So I just think it really is true that the Harvard Law School classroom today bears very little resemblance. A couple of years ago, we would have said that the only remaining vicious Socratic teachers were Elena Kagan and Elizabeth Warren. And so women had taken over the role, and that was great. And they were really sort of reliving it. And they were sort of showing that women can be just as, you know, like that as guys can. But basically, the classroom mode of interaction has lost a lot of the really scarily boot-camp like training. That’s not true for the gunners. So that the I mean, that dimension of the system is very continuous, intra-student hierarchy, but it’s less severe. The intra-student hierarchy is less extreme than it was in 1971 when it was. It was truly amazing. Just the differences among the self-understanding of Harvard Law School students. If there were 150 people in the section by the second semester with first semester, well, at the beginning it was all first-year courses, but by 73 or 74, it was just amazing that people were just arrayed according to their grades and their prestige and their class performance, and everybody had a so that’s really different. And the pluralization of reviews, it’s very meaningful that they’re now like seven or eight law reviews. That’s really, really, really good. So another very basic change, which is hard to quantify or be very sure of, is I do think that we specifically the crits combined with the law and economics movement, collaboratively politicized the self-understanding of a very large majority of all elite law professors. So the background understanding is I have no politics. Of course I vote and I’m a registered Democrat and I’ve never voted Republican in my life. However, as a law teacher, I have no politics. I think that experience is really, really uncommon today, and I think that’s a direct consequence of critical legal studies combined with law and economics. So us on the left, and they didn’t say they were political, but they were so blatantly political that the mask was removed. So the combination of us blatantly political was horribly, incredibly political, but denying it in totally implausible terms made everybody else much more self-conscious about their own politics and also polarized. So many people who had no politics became either left or right. In a sense critical legal Studies did them the favor of helping them find their reactionary self or their mildly social democratic self, of which, you know, it was a real being in them that was waiting to flower like, you know. And I actually think that at Harvard, the really right wing people from Charles Fried to Bob Clark, we really did something for them that helped them existentially fulfill their destinies and their being by creating a context where this mode of existence became respectable for them. So that’s a real we didn’t radicalize it. So total failure at the substantive level with the fantasy being to push the core way to the left. Totally failed to do that, partly because we grossly underestimated how much of our own generation, our own people born between, say, 1940 and 1960, how many of them hated the sixties and hated everything associated with it. So we all had the fantasy that we were a generational wave, but we actually weren’t. You know, Alito and Roberts are my exact contemporaries. You know, they’re me. They’re just, you know, so that’s something we really underestimated. We underestimated that. [94.0s] But the other thing about it is that we didn’t succeed in getting the the polarization that we wanted. Should it? We would have liked it. Politicization is great. It would be good if it was more overt. But I think it happened. So that would be another thing. So the classroom, the politics of legal scholarship, bad consequence, a very large part of the heritage of legal realist, super sophisticated awareness of ethical and political issues in case law, which was taught through the Socratic method when it was done incredibly brilliantly, is gone. So the combination of more self-conscious politics, tenure anxiety of young professors in a politically fractured thing, they’re much they’ve got they’re much more self-protective. So on the one hand, everyone knows they’re political, but young people are aware that they’re in a politically complicated charged atmosphere and they’re unbelievably careful and cautious often. And a new style post-Socratic style is often, I would say, more black letter, actually, with little bits of policy than it was in the realist period. Then It was more actually sophisticatedly anti-formalist than it is now. So this is a sort of horrifying — that would be a bad consequence.

Abby Marr [00:31:42] Thank you so much. So we’re out of time. But I wanted to give you the space to say anything else you would like to about the life cycle of CLS.

Duncan Kennedy [00:31:50] Up like a rocket, down like a stick.

Abby Marr [00:31:53] Okay. Thank you so much.

Jon Hanson [00:31:57] Thanks for listening to this episode of the Critical Legal Theory podcast. If you’re enjoying these interviews, I hope you’ll subscribe to us wherever you get your podcasts. And please rate us and leave us a nice review to help us expand our audience.