PART 1: TWICE AS HARD, HALF AS MUCH

Overworked, and underpaid

His brother sighs from the bunk above him—he doesn’t have to get ready for school for another two hours—but Travis1 cannot go back to sleep. Travis rolls over to turn off the 6 AM alarm telling him it is time to get ready for work. His first job starts at 7 AM and his head will not hit the pillow again until well past midnight when he arrives home from his third job. Since he graduated from High School, Travis has worked an average of 62 hours a week across his three jobs: building maintenance, security, and restocking a home improvement store’s warehouse. His hourly pay for each of his jobs ranges between $12 – $14.50, and despite how hard he works, he has neither the capital nor the credit to rent an apartment – he presently lives at home, sharing a room with his younger brother.

But compared to many of his friends who struggle to find steady work, Travis, who works regularly and is paid only slightly below the living wage,2 is doing pretty well. If you ask Travis, he is living the American Dream*. At 21-years-old he can afford his medical expenses and is slowly but surely paying off a used car. He has good insurance and can buy a new pair of shoes for work if he needs to. And while he has not had a weekend off since he could remember, he is still hopeful that one day he will have the security his mother dreamt of when she immigrated to the United States.

Over the past half-century, it has become standard practice for even the nation’s wealthiest corporations to cut costs in the form of wages and benefits under the guise of prioritizing profits. As the cost of living continues to rise at rates above inflation, many Americans must work more hours to maintain the standard of living their parents attained, lending new meaning to the adage shared within the Black community: “you must work twice as hard, to earn half as much.”3

Absent legal intervention protecting America’s working class from unfair wages and federally mandated employee benefits, corporations and corporate laws will continue to redirect income growth to the upper class. As the rich continue to get richer at the expense of the working class, impacted Americans will have to work more hours to make ends meet. The consequent erasure of free time from American life will lead the next generation to ask, “what happened to weekends?”

Although GDP is growing, wages are eroding

The United States has the largest Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in the world, estimated to be well over $807 billion dollars as 2020.4 While the rate of increase has slowed since the 1950’s, the US GDP has averaged a positive rate of change since 1961.5

Despite growth of the economy at the expense of America’s working class, members of the lower rungs of America’s economic ladder see little to none of this growth.

The wages of the middle class have remained stagnant,6 and real hourly wages for the lower class continue to decline. In 2009, the federal minimum wage was raised to $7.25 per hour; thirteen years later it has remained unchanged. Yet, even to call the change from $6.55 to $7.25 per hour a raise feels disingenuous. When adjusting for inflation, the federal minimum wage has been eroding since 1968.7

The cost of living is skyrocketing

Whereas in the early 196’s, 70% of married couples with children could survive with one income source, today, 60% of families are dual income,8 and still doing worse financially than their parents.9 Additionally, there is only a 50% chance that someone will earn more money than their parents (down from 90% in 1940)10 Further, some millennials have noted that, even when they make more than their parents did at the same age, where their parents could purchase a home with a little over twice their annual salary, they have to spend five times more than their annual salary to purchase an equivalent home.11

Moreover, wage increases that match inflation fail to close the economic gap created by the difference in these rates. The cost of living is typically used to compare the expenses of one city versus the other, however, it also captures changes in the cost of maintaining a quality of life in a way that inflation, which simply measures the price of goods and services over time, cannot. For example, the projected annual inflation in 2020 was 0.62%.12 Yet, in 2019, the cost of housing increased by 3.2%, education costs increased by 2.1%, food prices increased by 1.8%, and the cost of medical care rose 4.6—from 1984 to today, the annual average out-of-pocket cost for health care in America has doubled and is presently $5,000.13 Many Americans are justified in their view that the cost of living is the greatest threat to their present and long-term financial security.14

The wealthy’s mass purchase of land and real estate exasperate income inequality

Additionally, contributing to the k-curve—named for the increasing assets of the wealthy, and the decreasing assets of the low and middle classes—are the mass purchases of property by America’s wealthiest.18 The purchase of land and property impacts the financial well-being of the lower classes in two manners: (1) it contributes to the increased cost of living, and (2) it stymies national economic growth and innovation as it is a risk-averse investment.

First, the acquiring of land by the wealthy increases the cost of living for the lower and middle classes. The US has not invested in building more homes,19 and yet the population of people who are looking to purchase homes is increasing.20 The increased demand and low supply of housing have led the cost of homes, and rental rates, to skyrocket for the lower and middle classes,21 while the upper class has benefitted from decreased mortgage rates and decreased rental rates.22 Grant Cardone, a real estate investor who manages a $1.4 billion portfolio of multifamily properties, regarding the costs of residential real estate stated in his interview with Yahoo Finance:23

“[W]ealthy people are picking up second and third homes like most people buy Skittles or the way we were buying toilet paper back in March [2020]. The average person is not able to grab a house today.”

Next, the nation’s wealthiest use land acquisition as low-risk and high return investments over innovative, job-generating ventures. Given the stability of land ownership over the volatility of the stock market, there has also been a rise in land ownership.24 Many of the nation’s wealthiest families have begun acquiring arable land en mass. As of 2016, the top 10% of wealthiest individuals owned 82% of the nation’s non-home real estate.25 This risk-averse behavior of purchasing land and property over-investing in innovative companies stymies job growth and wealth redistribution. Paul Mason, in the documentary CAPITAL IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY describes the problem: 26

“For the rich, it’s easier to keep your wealth away from productive, risky activity, and this is producing a new social story.

It’s easier to build a property, and maybe you don’t fill that property, maybe all the apartments in the property aren’t filled, but you know in five years’ time that property will be worth so much more, that your business is really to sit on assets and hope their value rises, rather than to try and make money by risking your money in activities like open a factory or invent something new.”

The accumulation of land and property as a wealth-generating, investment vehicle also creates a closed, risk-averse, circle of wealth— “in which assets are bought and sold by the same people, as value of purchases continues to rise”27—that directly excludes America’s working class in its distribution of income.

Consequently, Americans today are working more hours for a lower standard of living

Members of the lower-class work 22% more hours than they did in 1979 and over 1/3 of the adult population have to work on the weekend to meet their financial obligations.28 And as the American workday continues to metastasize to all parts of the week, essentially eradicating concepts of free time and family time, the profit margin of many executives continues to increase drastically.29

PART 2: HOW DID WE LET IT GET SO BAD?

The fact that 90% of American’s negatively impacted by the growing wage gap between the American upper-class and the working class begs the question, how did we let it get so bad? 30 Three major legitimizing narratives have allowed corporations to funnel wealth to America’s wealthiest without alarming America’s lower classes to the point of action: (1) The narrative of the American Dream* which places the responsibility of social mobility squarely on the individual, (2) The economic theory of trickle-down economics, that allows lawmakers to prioritize giving tax cuts and other financial benefits to the nation’s wealthiest with the idea that any wealth generated will “trickle-down” to the lower classes, and (3) the macro script of shareholder primacy, which allows corporations to shirk social responsibility, such as increasing wages and providing benefits, in order to “save money” on behalf of shareholders.

As David Brooks stated in his criticism of Ta-Nehisi Coates’ book Between the World and Me, the American Dream is a narrative of “equal opportunity, social mobility, and ever more perfect democracy [which] cherishes the future more than the past,”31 in which the individual is the sole owner of their destiny. Rags to riches stories are therefore celebrated by all classes. For the poor, these stories serve as a north star—with the right degree, enough hard work, and a little bit of luck, they too could be a millionaire. For those already at the top—those who fail to acknowledge how their privilege has put them in a situation where they started off ahead—the American Dream serves as a narrative to justify the hoarding of capital as a just reward for their hard work and ingenuity.32

Yet for many marginalized Americans, the injustice has always been too glaring to ignore—lacking all legitimacy. Ta-Nehisi Coates writes the following about his desire to sleep peacefully under the veil of the American Dream:33

“For so long I have wanted to escape into the Dream, to fold my country over my head like a blanket. But this has never been an option because the Dream rests on our backs, the bedding made from our bodies.”

The American Dream was never written in anything other than white ink. In a research study conducted by Stanford, Harvard, and the Census Bureau, data showed just how far-reaching racism is in American Capitalism. The researchers found that “Black boys raised in America, even in the wealthiest families and living in some of the most well-to-do neighborhoods, still earn less in adulthood than white boys with similar backgrounds…white boys who grow up rich are likely to remain that way. Black boys raised at the top, however, are more likely to become poor than to stay wealthy in their own adult households.”34

More, as of March 2021, Black women continue to make less than their white male counterparts for the same work. For every one dollar that a white non-LatinX male makes, a black woman only makes $0.63.35 According to a report on gender-wage inequality, the average Black woman, over the course of a 40-year career, loses an estimated $840,040 relative to the average man due to gender wage inequality: Native American women lose $934,240, and Latinas $1,043,800.36

Such egregious rates of inequality have made it difficult for many marginalized communities to genuinely believe the American Dream applies to them. 37 Thus, for many, the American Dream is viewed with an asterisk, as it does not apply to them. However, the outgrowth of inequality, now impacting white Americans in the working class, has recently led even more to question the legitimacy of the narrative of the American Dream: “In 2001, more than three out of four workers were satisfied that they could get ahead by working hard. In 2014, only slightly more than one out of two thought so.” 38

For those with enough privilege to believe in the attainability and reliability of the American Dream*, it has served as a narrative that takes blame for the lack of social mobility out of the hands of Corporations and into the hands of the individual or into the hands of non-Americans. As the New York Times reports: 39

“The self-interested power of the nation’s wealthy often goes unnoticed by voters, and is partly misdirected by right-wing rhetoric about issues like immigration. But it leads to lower wages, less product choice and abusive labor practices.”

The American Dream* therefore serves as a powerful and pacifying narrative, allowing corporations to escape responsibility while continuously robbing American workers of social mobility and a decent standard of living.

Trickle Down Economics

While lawmakers and politicians often acknowledge the growing wage gap, they continuously fail to implement laws and policies that would aid in wealth redistribution. In the 1980s, when Reagan went into office with the promise of undoing all the worker benefits and protections created during the New Deal, he used the economic theory of Trickle-Down Economics to justify relaxed regulations, and tax cuts to the wealthy (corporations and individuals alike). In short, Trickle-Down Economics stands for the idea that any tax breaks or benefits provided to corporations will stimulate business investment and those additional benefits will then “trickle-down” to everyone else. As stated by American economist, Joseph Stiglitz, “[t]he promise was that [through deregulation and tax cuts] the pie would be bigger, you would be getting a smaller percentage of a bigger pie, and your slice would get bigger.”40

This economic theory was based on a theory created by Art Laffer called the “Laffer Curve.” In short, the Laffer Curve is a U-shaped curve that show the relationship between tax rates and tax revenues; it suggests that lowering tax rates might increase tax revenue.41

While the Laffer Curve has a mountain of evidence proving its inefficacy, for example Kansas followed Laffer’s theory by cutting their tax rates by a third and the state went into a fiscal disaster,42 Laffer received a Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2019.43 The biggest fault of the Laffer curve is that it ignores the fact that it doesn’t’t apply to the rich.44 While it may be true that people in the lower and middle class may be further incentivized to work if they are taxed minimally, this is not true for the upper class.45 Those of the 1% do not take risks in the market, or spend their capital in a way that will “trickle-down,” instead they hoard their wealth in trusts and property.46 This is why, every year, even more of the GDP is hoarded by the top 10% while the rest of America gets a smaller and smaller slice of the pie.47

PART 3: CORPORATE INFLUENCE OVER LAW AND POLICY-MAKING

Not only are the nation’s wealthiest corporations and individuals amassing capital and land, but they are also accumulating political power—specifically the power to prioritize their own interests over that of the average American Laborer. Corporations, and the wealthy who manage them, are producing mass income inequality while facing little to no accountability.

The Corporate Oligarchy

Robert B. Reich, in his book The System, defines the concentration of power in the hands of wealthy corporations as a Corporate Oligarchy. In summarizing the concept, the New York Times states:

“For Reich, the big oligarchical companies have the lobbying and campaign-financing muscle to mold the rules in their own favor. They can win enormous tax cuts, suppress financial and environmental regulations, acquire new patents and subsidies, fight for free trade — it is a long list. For years, they successfully battled against higher minimum wages and labor laws that restricted their union-busting efforts.”

Congressional entanglement with Corporate Interests

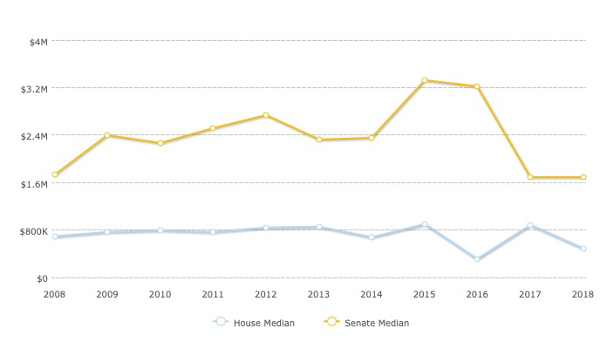

However, wealthy corporations are not the only questionable actors contributing to the stagnation of wages and lack of worker benefits. Members of Congress share many interests with corporations, as they are wealthy stakeholders who benefit from lax regulation of businesses. According to a study by the Center for Responsive Politics, 261 of the 535 members of congress (nearly half) are millionaires:56 phrased another way, almost 50% of Congress are members of the top 1% income earners in the US. Moreover, according to the Washington Post, “some congressional financial interests intersected with public actions taken by legislators: 73 lawmakers sponsored or co-sponsored legislation that could have benefitted businesses or industries in which either they or their families were involved or invested.

Figure 1: Estimated Wealth of Congress Members Over Time (Source: Opensecrets.org)

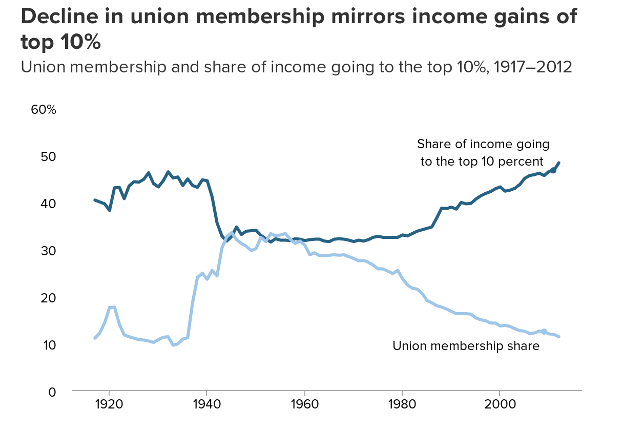

As the Economic Policy Institute (EPI) noted in its report analyzing wage stagnation, the concentration of political power among those with the most income, wealth, and power prevented the adoption of laws to modernize our labor–management system and enable workers to pursue collective bargaining.” This is significant because “the erosion of collective bargaining” accounts for one-third of the growth of wage inequality as collective bargaining “not only raises wages for organized workers but also leads other employers to raise the wages and benefits of nonunion workers to come closer to union wage standards.”

Figure 2: Estimated Wealth of Congress Members Over Time (Source: Economic Policy Institute)

Thus, it is clear that the link between wealth and political power is more than a mere correlation—it is a causal link to the inactivity of Congress in adjusting the federal minimum wage to rates at or above the poverty level and creating federally mandated benefits—such as paid sick leave, paid parental leave, paid vacation, or maximum workweek lengths.57 Corporations are Congress’ most important constituents, even as some American’s are forced to work 94 hours a week to be able to live off of minimum wage.

Possible Solutions

There are several steps we can take to ease the burden of the working class. The Economic Policy Institute (EPI) outlines in a report steps that will “raise wages, protect workers’ rights, and fix our economy.58” Their recommendation to strengthen the rules that support good jobs and the steps it entails —raising the minimum wage to $15 and index it to wage growth, enacted paid leave, both sick and family leave, and eliminating discrimination in hiring, promotion, and pay—is especially notable as it depends on Congress enacting legislation that may run counter to their personal interest, as outlined earlier. Thus, other recommendations point to the Courts instead of the legislature. For example, in his 2020 campaign, Senator Bernie Sanders recommended overturning the Supreme Court ruling in Buckley v. Valeo, which declared that money is speech. However, the issue produced by decision-makers with proximity to wealth prioritizing their own interests is still relevant—in 2009, 7 of the 9 sitting justices were millionaires.59

Thus, although many great solutions being offered by various actors, they are all met with the same barrier: the deep entanglement of corporate interests with the private interests of our decision-makers.60 The legislative priority, should therefore be to enact legislation that ends the influence of corporate money on elections. As suggested in the Free and Fair Elections Amendment drafted by Free Speech For People, a national non-profit non-partisan organization that advocates for free and fair elections, whatever law(s) is enacted to address this issue, it should:61 (1) set limits on federal campaign contributions and spending; (2) prohibit “corporate spending in the political process (as existed prior to the Supreme Court’s ruling in Citizens United v. FEC)”; (3) require Congress to develop a system of public campaign financing for all federal candidates who qualify for the ballot; and (4) allow the States to set reasonable limits on campaign contributions and spending in state and local elections.

CONCLUSION

Without laws that promote the well-being of all Americans, such as wage increases, progressive taxes, and free secondary education and health care, the decline of the American standard of living will continue. However, we are unlikely to see any such action in the legislature if we continue to allow those with wealth, both corporations and individuals, to make decisions regarding our social wellbeing. Unless we begin to reseparate wealth from politics, we will cause more and more Americans using all parts of their day to work, in hopes of escaping the hamster wheel that is the reality of our economic system. Absent intervention, within a generation, our children will have to work so many hours to compensate for low wages that many will come to ask, “what happened to weekends?”