PART 1: GUN VIOLENCE—A PUBLIC HEALTH CRISIS

The American crisis of gun violence can hardly be overstated. The gun homicide rate is twenty-five times higher than in other wealthy countries; the gun suicide rate is eight times higher.1 In recent years, political appetite for gun control has appeared somewhat greater, with spikes in interest generally occurring after mass shootings, perhaps especially when the victims are white children. But mass shootings are not the major cause of death by guns, and proposed reforms tend to ignore the root causes of gun violence.

In 2020, 43,541 Americans were killed by guns, with the majority of these deaths—about 55%—attributable to suicide.2 Another 5% were shot unintentionally, and 3% were killed by police officers, for a total of about 63% of gun deaths not caused by a “civilian” intentionally shooting another person.3 By contrast, murder/homicide (not by police officers) and “defensive gun use” accounted for about 36% of deaths. Of those, about 3% were the results of mass shootings or mass murders—meaning mass shootings and murders were responsible for fewer than 1% of gun deaths overall.4

Underlying causes of gun violence almost certainly include poverty, income inequality, underfunded public housing, schools, and services, and, of course, the existence of firearms.5 And yet, current proposals for gun reform overwhelmingly focus on individualized solutions, like background checks and enhanced criminal penalties, as well as strategies aimed primarily at preventing mass shootings, such as assault weapons bans. These policies place the blame on individual gun users—particularly when those users are Black men—and shield firearms and ammunition manufacturers, distributors and dealers from any liability for their lethal products.

It is no surprise, then, that these same corporations have played a large role in shaping the narrative of gun violence that underlies even ostensibly progressive gun control proposals. As this article will demonstrate, corporations have nurtured our society’s focus on individual people as the loci of gun control; have supported the treatment of gun violence as a crime problem, rather than a public health problem; and have promoted the anti-Black racialization of the Second Amendment, all to their own benefit.

PART 2: “THE WRONG HANDS”—HOW WE TREAT GUN VIOLENCE AS A PROBLEM OF BAD ACTORS

The familiar NRA catchphrase, “Guns don’t kill people, people kill people” is often mocked on the left. And yet, our public narratives around gun violence, and our “progressive” solutions to it, consist almost entirely of stories about “dangerous” individuals.

First, we are hyper-fixated on mass shootings. A 2019 study found that one mass shooting leads to a 15% increase in the number of gun regulations proposed in the state where the shooting occurred.6 Tragedies such as the Sandy Hook and Stoneman Douglas shootings—which together led to the deaths of thirty-seven children, most of them white—seem to provoke especially ardent cries for gun control: whether those proposals are background checks to keep mentally unwell people from purchasing firearms, armed guards to “take down” school shooters, or bans of the types of weapons that mass shooters often wield.

But as the statistics above demonstrate, mass shootings are responsible for a very small percentage of gun deaths. That does not make them less devastating, but it does belie the notion that gun control writ large should be focused primarily on preventing them.

Second, when we do pay attention to more run-of-the mill gun deaths, our fixation shifts to crime. A recent Google news search of “gun violence” turned up twelve articles on the first page: three about mass shootings, three about increases in gun violence in Philadelphia, New York, and New Orleans, two about an upcoming Supreme Court case on concealed carry permits, and two about the rise of gun violence during the pandemic.7 Both of those last two articles—one on the NBC News website and the other in the Washington Post—focused almost entirely on homicide.8

And yet, as the numbers show, homicides are the minority of gun deaths in the United States. Moreover, contrary to what media accounts suggest, white men and Black men are at similar risks of dying by gun violence. The difference is that white men are more likely to fatally shoot themselves, while Black men are more likely to be fatally shot by someone else.9 But while the former is treated as a public health problem, the latter is treated as a racialized epidemic of lawlessness.

This focus on homicides rather than suicides serves to make Black men the image of gun violence in the popular imagination. The racist concept of “Black-on-Black” crime, along with racially loaded depictions of many Black neighborhoods as “dangerous,” solidify a narrative of gun violence as a problem of criminality, rather than a symptom of injustice. Indeed, articles about these “dangerous neighborhoods” rarely mention the red-lining, underfunding of public services, War on Drugs, and displacement that inhabitants have endured, nor recognize that homicide and suicide can both be manifestations of trauma.

As a result, arguably the strictest form of gun control is the criminal legal system: specifically, felon-in-possession statutes. The federal version, 18 U.S.C. § 922(g), along with its state and local counterparts, criminalizes the possession of a firearm by anyone who has a felony record. These laws effectively nullify the Second Amendment rights of one third of Black men.10

FIP statutes punish people merely for possession, but the U.S. punishes all crimes involving guns particularly harshly. In the 1990s, the federal government initiated “Project Triggerlock,” under which U.S. Attorneys nationwide began encouraging the federal prosecution of gun crimes, in order to obtain higher sentences.11 Project Triggerlock was hugely popular, and spawned a plethora of local programs, all aimed at incarcerating people for longer amounts of time.

Public opinion on criminal law is more progressive than it was thirty years ago. But incarceration as a form of gun control remains popular. Consider what is currently happening in Washington, D.C. In 2019, then-U.S. Attorney for the District of Columbia Jessie Liu, along with Mayor Muriel Bowser, unveiled a new policy of moving all FIP cases from local to federal court, where those convicted faced double prison time. The stated reason? To “curb the illegal guns that fueled a spike in homicides.”12 Later, after a year and a half of litigation, the policy was revealed to apply only in predominantly Black areas, though that aspect of the policy has apparently been abandoned.13 Although it has attracted local and national opposition, President Biden recently decided to continue it.14

Given our twin fixations on mass shootings and crime, it is no wonder that today’s proposed gun control measures most often seek to keep guns out of the “wrong hands.” In other words, proposed regulations are aimed almost exclusively at the consumer end, rather than at the industry itself; and often contain an additional layer of racist stereotypes about group-based propensities to violence.

Consider a press release from Senator Dianne Feinstein, entitled “Mass Shootings Involving Assault Weapons Kill More People Than Other Weapons.”15 Typically, the release mocks the “guns don’t . . .” NRA catchphrase: and then lists a series of bills the Senator has introduced, all of which focus primarily on individuals, or mass shootings.16

The major gun control organizations sing a similar tune. Everytown for Gun Safety—incidentally funded mainly by Michael Bloomberg—highlights three solutions to gun violence on its website homepage: background checks (and closing a related loophole called the “Charleston loophole”), secure gun storage, and violence intervention. Only if a visitor goes to the “solutions” page, scrolls past nine proposals to keep guns out of the “wrong hands,” and another seventeen focused on permits, schools, safety training, etc., will she find mention of industry. The word “suicide” does not appear once.17

Likewise, while the “issues” page of the Brady Center to Prevent Gun Violence website lists topics such as loopholes, enforcement, and gun ownership, it mentions neither suicide, nor industry.18

PART 3: HOW THE GUN INDUSTRY CAPTURED GUN CONTROL

The key to the Second Amendment is the marketplace: how the NRA became a proxy for the firearms industry

The “wrong hands” narrative is no unhappy accident. To the contrary, the firearms industry has promulgated it over the past five decades, largely through the National Rifle Association, or NRA. So in order to understand how the industry captured gun control, we must first understand how the NRA transformed itself from a sportsmanship group into a corporate lobbyist.

For its first century, the NRA was essentially an apolitical riflery club: it organized fun events for shooting enthusiasts. It was only in the 1970s that it began to morph into an aggressively political lobbyist. This was due in part to the ascent of a far-right wing within the NRA, and in part to FEC and Supreme Court decisions that allowed the NRA both to fundraise and to donate more.19 Conveniently, this time was also the beginning of deregulation, tort reform, and trickle-down economics: the perfect moment for right-wing individualists and profiteering executives to join hands.

In the 1990s, Big Tobacco litigation rattled gun industry executives, who feared their businesses would be next. And so it was in 1999 that the NRA publicly swore its fealty to industry. Then-NRA-president, Charlton Heston, spoke in no uncertain terms: “Your fight has become our fight,” he said. “Your legal threat has become our constitutional threat.”20 Little has changed; current NRA Executive Vice President Wayne LaPierre has said that “the key to the strongest defense of the Second Amendment is the marketplace.”21

The NRA’s finances are notoriously inaccessible. But in 2013, the Violence Policy Center estimated that the gun industry contributed between $19.3 million and $60.2 million to the NRA (the range is because they calculated this number based on the “giving” bracket each company was within in the NRA’s donor program).22 Granted, the NRA’s annual revenues are between $226 million and $362 million;23 but the Center’s estimate applied only to the NRA’s official “Corporate Partners Program.”24 Add donations from wealthy “individuals” (see next paragraph), industry sponsorship of NRA programs, corporate fundraising to benefit the NRA, and advertising revenue (NRA publications are essentially trade catalogues), and the proportion of revenue from industry is likely much higher.25

Besides, the NRA’s website barely bothers to disguise the insidious web of corporate interests that constitutes its core. For example, it prominently celebrates its top ten “industry allies”: seven firearms manufacturers, two firearms retailers, and one firearms marketer.26 It also celebrates its top individual donors as the “Ring of Freedom,” presented as a smiling group of anonymous elderly white people. With some help from Google Images, one quickly discovers that most or all are top firearms executives:

Figure 1: The “Ring of Freedom”—Top Individual Donors to the NRA (Source: Nraringoffreedom.com (highlighting added by the author))

Left to right (highlighted individuals): James Debney (former CEO of American Outdoor Brands Corporation, parent co. of Smith & Wesson); Frank Brownell III (Chairman of the Board of Brownells, a firearms supplier); Pete Brownell (Frank’s son, and CEO of Brownells; former NRA board member); Bob Nosler (was founder/owner of Nosler Co., a firearms manufacturer; former NRA board member); Larry Potterfield (founder/CEO of MidwayUSA, a firearms retailer); Mike Strum (former CEO of Strum Ruger & Co., a gun manufacturer); Judy Woods (widow of John Woods, who was senior VP at E.F. Hutton & Co., a then-stock brokerage). The author was unable to identify the other individuals.

Despite the NRA’s obvious corporate nature, journalists rarely refer to it as a trade organization. Instead, they call it a ‘grassroots’ lobby or a collection of gun-rights activists.27 Even ACLU National Legal Director David Cole barely mentions industry in his account of the NRA’s considerable influence, emphasizing that “[t]he real source of [this] influence is [the NRA’s] remarkable ability to mobilize its members and supporters at the ballot box.”28 Indeed, he appears to dispute the above numbers, taking at face value the NRA’s claim that “[m]ost of [its] resources come not from the gun industry, but from . . . millions of ordinary citizens.”29

Admittedly, the NRA’s power may be weakening. Currently, it faces a serious threat from New York Attorney General Leticia James, who is suing NRA leadership for violating its fiduciary duties through gross misuse of organizational funds, like family trips to the Bahamas. LaPierre has filed for bankruptcy, to try and escape the lawsuit, and relocate the NRA to Texas.30 (Notably, he filed without telling the board; they then retroactively approved his filing, and LaPierre testified that he was unaware of the organization’s mis-expenditures.31)

But it is undeniable that the NRA has consolidated and wielded the firearm industry’s power to massive effect for the last half-century. Whether opponents are able to effectively seize on its current moment of weakness remains to be seen.

Regulatory capture: How the gun industry made itself accountable to no one

Once upon a time, people blamed the firearms industry for gun fatalities. The NRA made sure to put an end to that: and took down pretty much all industry regulations along the way.

Despite being a “non-profit,” the NRA does not spend most of its revenue on education, hunter services, or recreation. Rather, its largest expenditure is on legislative influence—in 2014, to the tune of 97.7 million dollars.32 It has stymied multiple government regulatory attempts; in 1996, for example, it secured passage of the Dickey Amendment, prohibiting the CDC from funding research that might lead to gun control.33 In 2004, it helped prevent the renewal of an expiring ban on assault weapons;34 over the following decade, annual U.S. rifle production rose by nearly 38 percent.35 Notoriously, the NRA rates Congresspeople, signaling who their membership should support (although, the influence of these ratings appears to be on the wane).36 And, it helped disembowel the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms (ATF): ATF’s budget has remained nearly stagnant since the 1970s, and it is subjected to such a Kafka-esque assortment of rules that it is unable to enforce the few regulations that do exist.37

But the NRA’s greatest accomplishment is the Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms Act (PLCAA). In the 1990s, when the gun industry began to face lawsuits for rising gun fatalities, many courts dismissed the suits under state immunity laws; but the gun industry was still nervous.38 So, they eliminated the problem: they convinced Congress to pass the PLCAA in 2005, giving the industry blanket immunity from tort lawsuits alleging harm caused by their products. Even within the tort reform movement, this was remarkable: it is the only time that Congress has given an entire industry near-total immunity. A study in the American Journal of Public Health found “evidence that the lawsuits [prior to the PLCAA] influenced the firearm industry’s conduct,” with some manufacturers agreeing to change products, marketing, and business/sales practices.39 After the passage of the PLCAA, such lawsuits became almost impossible.

Occasionally, canny plaintiffs do sue under one of the narrow PLCAA exceptions; but such lawsuits are cumbersome, and rarely succeed. For example, Gary, Indiana has been attempting for twenty years to hold Smith & Wesson liable for the costs of gun violence to the municipality.40 In 2019, the Court of Appeals of Indiana finally held that Gary could proceed to trial on the limited issue of whether Smith & Wesson had behaved unlawfully (rather than negligently). There is no record of the trial having occurred.

The gun industry’s regulatory capture is near complete. But even then, corporate law provides the usual safe harbors. For example, when Sandy Hook families successfully drafted around the PLCAA in a claim against Remington, the corporation pulled a classic move: filing for bankruptcy.41 And of course, corporate law holds that it would be illegal for the boards of firearms companies to consider public safety; the only stakeholders they may serve are their shareholders.

Discourse capture: How the gun industry promoted “tough-on-crime” policies to criminalize Black men and distract from its own liability

We need someone to point the finger at for gun violence, and the industry figured out pretty early on who that should be. Indeed, the industry is not, as often suggested, universally anti-regulation: it actually favors regulation, when it comes in the form of incarcerating Black men. James Forman, in his book Locking Up Our Own, explains the NRA’s role in the wave of “tough-on-crime” laws passed in the 1980s and ‘90s. For example, the NRA was so supportive of the creation of mandatory minimums in Washington, D.C., that it “dispatched its members across the city to distribute fifty thousand pamphlets encouraging citizens to ‘Vote Prison Time for Violent Crime.’”42 Later that decade, President Reagan “signed into law the NRA-backed Firearm Owners Protection Act, or FOPA. It increased sentences for gun crimes, even as it eased restrictions on the supply of guns. The NRA calls FOPA ‘the law that saved gun rights.’”43

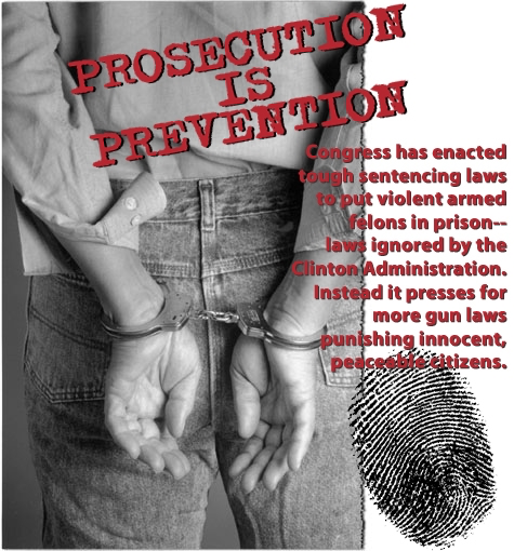

Figure 2: Prosecution is Prevention—An NRA Graphic from 2000 (Source: nraila.org/articles/20001017/prosecution-is-prevention)

Fourteen years later, the NRA Institute for Legislative Action composed a long missive, calling on President Clinton to more strictly enforce FIP statutes.{{Prosecution is Prevention, NRA Institute for Legislative Action (October 17, 2000), https://www.nraila.org/articles/20001017/prosecution-is-prevention.

}} It painted a highly racialized picture of a “criminal” who illegally purchased a weapon from the fictional “Shady Gap Gun Store”:

Put a criminal face on an illegal gun buyer. He is drug dealer from Washington, D.C., with adult convictions for sale of narcotics, armed robbery and assault on a police officer. He is currently on parole for those offenses and has been indicted for a subsequent drug possession charge in the District of Columbia and is awaiting trial under a personal recognizance release. He is also wanted for an armed robbery charge in neighboring Prince George`s County, Maryland. There are pending fugitive warrants on him issued by courts in Indianapolis, Indiana. By any measure, this is a bad guy. For Washington, D.C., this hypothetical composite is no exaggeration. This is the criminal profile feared by the public.44

Gun lobbyists continue to promote criminalization of gun crimes, thereby distracting from their own liability, and to inflame white fears of Black people with guns—presumably, to sell more guns to those same white people.45

Constitutional capture: How the gun industry revolutionized Second Amendment jurisprudence and created a racialized “right” to own firearms

The gun industry not only convinced us to blame the “bad guys” for gun violence: it has also convinced us that the “good guys” need guns to keep society safe, such that it would be dangerous to threaten the industry with liability.

For most of US history, courts held a clear consensus on the Second Amendment: it protected the rights of state militias to bear firearms, not the rights of individuals. But in the 1970s, the NRA began a mission to change this interpretation, culminating in the landmark decision DC v. Heller (2008), which held that all individuals possess a constitutional right to bear arms.46

Cole describes the NRA’s four-decade strategy to achieve this end. Because its individualist Second Amendment interpretation was so unorthodox in the ‘70s, it started with the states, not the federal government. For example, it pushed to “pre-empt” city gun ordinances (which tend to be the most restrictive), convincing states to pass laws giving themselves sole authority to regulate firearms.47 In 1979, seven states had preemption laws; by 2005, forty-five did. The NRA also encouraged states to amend their constitutions to include a right to bear arms. By the time of Heller, forty-four state constitutions included such a right, “and nearly all of those protected an individual right.”48 Another successful NRA campaign aimed at expanding “concealed carry” protections; ultimately, all fifty states passed them.49

Meanwhile, the NRA infiltrated both Congress (as described) and the Executive Branch, garnering political support. By helping to elect politicians like George W. Bush, it secured important strategic victories, like a Department of Justice opinion affirming an individualist interpretation of the Second Amendment,50 and influence over Bush’s two Supreme Court nominations.51 The NRA also paid legal scholars who published articles favoring its position.52

But perhaps its nastiest move was the development of an impliedly white “self-defense” narrative. As most Americans stopped hunting, the industry needed a new justification for its products. They found it in “danger,” especially “dangerous” Black cities, for example after the 1992 Los Angeles Uprising.53 The concealed carry campaign was one aspect of this narrative; another was the NRA’s encouragement of “stand your ground” laws, which allow a person to use lethal force even when he can retreat instead. Florida passed the first such law in 2005 (under which a jury infamously acquitted George Zimmerman of murdering Trayvon Martin, an unarmed Black teenager); as of 2016, thirty-two states have them (or equivalent judicial decisions).54 Today, gun manufacturers and advertisers shamelessly use fear to sell; Smith & Wesson has “home defense” and “concealed carry” product lines,55 while Ruger produces a gun called the “Security-9”:

Figure 3: Ideal for Everyday Carry and Self Defense (Source: https://www.ruger.com/products/security9/models.html)

The propagation of this racist “defense” narrative, under the guise of the Second Amendment, has also obscured a less-told story: guns as necessary to protect against white terrorism. Forman describes how in the 1970s, D.C. Council Member and Black nationalist Doug Moore argued that gun ownership was essential for Black people to truly achieve equal protection:

[Gun ownership was] a tool of collective self-defense against violent whites. If D.C. was to give up its guns . . . that would ‘make it difficult for the people of this city—many of whom are black—to defend themselves’ against gunslinging vigilantes from neighboring majority-white states.56

Forman traces the centrality of gun ownership in Black liberation movements throughout the past century, beginning after Reconstruction, when many states banned Black people from owning firearms.57 He notes that the government enforced concealed weapon laws mainly against Black men, and that by 1900, such laws were “one of the most consistent instruments of black incarceration.”58

But white America—and the gun industry—was never interested in this story. Indeed, restrictions on gun access began gaining traction in the 1960s, just as groups like the Black Panthers began publicly carrying weapons.59 Today, industry-fueled self-defense narratives continue to exclude Black people. The NRA never said that if only Ahmaud Arbery had had a gun, he could have protected himself from his white killers. The media paints Black neighborhoods as “dangerous,” but it never says “therefore, Black residents need guns to protect themselves.” To the contrary, as already noted, we permanently ban one third of Black men from possessing firearms. A former client, a middle-aged Black man who had endured many periods of homelessness, once laughed as he told me about his long criminal record: “a lot of them are for having a gun—look, I was in South Boston in the ‘90s, of course I had a gun.” But the Second Amendment, it seems, did not apply to him.

PART 4: HOW TO APPROACH GUN VIOLENCE AS A PUBLIC HEALTH ISSUE

So what could real gun control look like, if we wrested it back from the industry’s clutches? I propose five solutions:

Fund national research

We must repeal the Dickey Amendment, and vastly increase support of CDC and NIH gun violence research, an area which public health experts call “severely underfunded.”60 It is dangerous and racist to treat homicide and suicide as fundamentally different when they may have similar underlying causes; it is simply bad policy to advocate reforms without knowing what actually works.

Blame industry, not consumers

We need to stop blaming individuals in public discourse. When we tackled cigarette smoking in the 1990s, we didn’t incarcerate smokers: we attacked Big Tobacco. As the opioid epidemic rages, at least some communities and organizations have tried to stay away from demonizing users: instead, we are fighting opioid manufacturers in court. (Though notably the public did not use this same approach when communities, often Black, suffered from the 1980s crack epidemic.)

Shooting a gun and smoking a cigarette are not the same, notwithstanding that cigarette smoking can seriously harm both oneself and nearby people. But the point is that focusing on stopping the “wrong people” from obtaining guns gets the power analysis wrong. It’s not individuals who are responsible for our national crisis: it’s an industry that profits from its lethal products, and a captured society that refuses to hold it accountable.

Reverse racist criminal policies

Relatedly, we must stop using the criminal legal system as form of gun control. The mass incarceration of Black men is not only cruel and unjust: it also likely exacerbates some of the very conditions that contribute to gun violence in the first place, such as trauma, hopelessness, and poverty. We cannot incarcerate our way out of a public health crisis, nor should we try to do so.

Regulate guns like we do food, lipstick, or phones

We must amend the Consumer Protection Act, which does not allow the Consumer Product Safety Commission to impose safety standards on firearms.61 And we must properly fund the ATF, so that it can actually regulate industry.

Repeal the PLRAA

We must allow suits against the firearms industry for unsafe products, marketing and sales. Repealing the PLRAA will require a big fight, but some are already doing the groundwork. Recently, New Jersey Attorney General Gubir Grewal subpoenaed Smith & Wesson, ostensibly to investigate advertising fraud, but really to access secretive internal records.62 He hopes to inflame the public’s sentiments with his findings, just as state attorneys general nationwide did with Big Tobacco.

CONCLUSION

The firearms industry has told us to make sure that guns don’t end up in the “wrong hands.” It’s a clever trick, playing to racist stereotypes, psychological tendencies to blame individuals, and the devastating spectacle of mass shootings.

But looking at the wrong hands is, well, wrong. It’s the hands that saturate our neighborhoods with weapons, the hands that profit from American blood, the hands that send ordinary men to prison, and corporate executives to the Bahamas: it’s these hands that we must watch. For they are the hands with blood on them.

FURTHER READING

For a detailed account of “gaps” in gun industry regulation, see Chelsea Parsons, Eugenio Weigend Vargas and Rukmani Bhatia, The Gun Industry in America: The Overlooked Player in a National Crisis, Center for American Progress (August 6, 2020), https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/guns-crime/reports/2020/08/06/488686/gun-industry-america/.

For more on the NRA’s finances, and particularly its classification as a “non-profit,” see Alexandra and Daniel O’Neill’s article, The NRA, A Tax Exempt Loaded with Private Interest, cited in full in Endnote 22.