The Price of Environmental and Human Safety: $3

The “Amazon Chernobyl”

In Ecuador’s Amazon Basin sits some of the world’s most diverse ecological systems. Within the region are several indigenous communities, including the Huaorani people, the Kichwas, the Shuar, the Achuar, the Taromenane and the Secoya. Each of these communities have varying degrees of exposure and communication with “modern life,” and primarily live off the ecologically diverse system in which they reside (for example, most of their medical practices rely on natural substances found in the jungle).1 Over 1 million indigenous people live in Ecuador’s Amazon Basin—their livelihood, health, and culture depend on the preservation of the jungle.2

Unfortunately for these communities, within the Amazon Basin also sits massive oil reserves. When Texaco (purchased by Chevron during litigation in 2000 and hereinafter referred to as “Chevron”) discovered oil in Ecuador in 1964, it moved in.3 Quickly. Chevron, out for a profit, decided to save money over protecting local indigenous communities. To save $3 per barrel, which amounts to $5 billion over the 20-year period of operation, Chevron ignored regulations and purposefully dumped 16 billion gallons of toxic waste into local rivers and pits.4 This waste infiltrated farmland and ground water, carrying illegal levels of barium, cadmium, copper, mercury, lead, and other damaging, carcinogenic metals. The environmental disaster spanned over 1,700 square miles and impacted thousands of people.5 The corporation created approximately 900 illegal waste pits, which were found to contain 200 times the amount of contamination deemed acceptable by the United States’ and worldwide standards.6 The damage is so extensive that some have referred to it as the “Amazon Chernobyl,” a reference to the 1986 nuclear disaster.7 A conservative estimate shows that the destruction in Ecuador increased certain cancer rates 15-fold in local indigenous communities.8 Not only did Chevron purposefully dump this toxic waste into the region, it claimed that the waste would benefit the populations residing there. According to several witnesses, notably including a leader of the Ecuadorean Secoya people, Humberto Piaguaje, Chevron told communities that the oil wastes were medicinal and filled with helpful nutrients.9 Chevron knowingly manipulated communities while permeating cancerous toxins throughout their food and water.

In came Steve Donzinger, a human rights lawyer from the United States. Joining a team of other American and Ecuadorean lawyers (including Patricio Salazar Córdova, who is still litigating this matter), Donzinger stepped in to fight the good fight, suing Chevron in its home jurisdiction of New York in 1993. Chevron removed the case to Ecuador, likely because Ecuador does not have class-action litigation and thus the class had to be broken up, and then continued to argue jurisdictional issues to draw out the legal battle. After 18 years of cut-throat litigation, the indigenous communities got some justice in the form of a $9.5 billion verdict. This verdict has been validated by more than a dozen Ecuadorian judges.

Chevron’s Legal “Strategy”

Chevron, though, was not done taking advantage of the American judicial system to prioritize profits over environmental and human rights. Chevron did not hide that this was their tactic. According to an attorney involved in the matter, rather than ever attempting to mount a defense based on the facts, the lawyers at Gibson Dunn strategically manipulated the law—knowing that the facts were simply not in their favor, they decided to use money and power instead. To avoid paying the community reparations for the damage to their land, their health, and their community, Chevron has dissolved its presence in Ecuador.10 Dissolving its presence makes the $197 billion corporation essentially judgment-proof.11 Plaintiffs thus had to file cases in Canada, Brazil, and Argentina to acquire Chevron assets and obtain their court-awarded payment.12 This litigation is ongoing. Canada has upheld the judgment but ruled that the plaintiffs would not be able to pierce the corporate veil in Canada. Piercing the corporate veil would allow the plaintiffs to seek the assets of the shareholders of the corporation, rather than relying on assets of the corporation itself. The court held that, even though owned by the same parent corporation, Chevron Canada is a subsidiary, and thus piercing the veil would collapse their entire corporate law structure. The plaintiffs appealed, and the Supreme Court of Canada denied the appeal. Thus, Chevron is claiming a legal win, as the corporation still cannot be held accountable.13 Meanwhile, with indigenous communities searching for help for basic survival, Chevron shifted focus and, with it, the public narrative. The corporation sued Donzinger back in the Southern District of New York, claiming he obtained the judgment fraudulently.

Rather than pay the legal judgment, Chevron is now in the midst of a $2 billion campaign aimed at demonizing Donzinger and the indigenous community he represented. In the center of this campaign is a civil lawsuit against Donzinger and 47 villagers, claiming that the initial lawsuit against Chevron was just a “racketeering conspiracy.”14 The law Chevron is suing under, the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (“R.I.C.O.”), was originally designed to allow for criminal prosecution of crime families and gangs, and the civil aspect was included as a method for allowing families of victims claimed by these organizations to find some compensation.15 Chevron, armed with 60 law firms and 2,000 legal professionals in its arsenal, purposefully chose a judge with a notoriously pro-business outlook.16 Whether there is a direct tie between the corporation and Judge Kaplan has not been proven, but the selection of this judge was not an act of fate. According to an academic involved in the litigation, Judge Kaplan is known for “protecting the protected industries,” including oil and tobacco. Judge Kaplan thus ruled in favor of Chevron, based on the testimony of one witness, Alberto Guerra, who, incidentally, is also in Chevron’s arsenal.17 Chevron lawyers had actively pursued Guerra—they paid him hundreds of thousands of dollars, moved him and his family to the U.S. with a monthly salary 20 times his previous earnings, and had Gibson Dunn prep him 53 times.18 Even after becoming aware that the witness had been bought and committed perjury, Judge Kaplan did not abandon the verdict and maintained the ruling in Chevron’s favor. Judge Kaplan even blamed Donzinger for the lack of justice, writing in the opinion:

“The saga of the Lago Agrio case is sad. It is distressing that the course of justice was perverted. The LAPs received the zealous representation they wanted, but it is sad that it was not always characterized by honor and honesty as well. It is troubling that … what happened here probably means that ‘we’ll never know whether or not there was a case to be made against Chevron.’”19

This litigation is ongoing, with Steve Donzinger now fighting for his own freedom—he was stripped of his legal license and placed under house arrest. Judge Kaplan is now being sued for violating the judicial code of conduct as the case against Donzinger moves up through the 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals.20

Big oil moved into the region in 1964. It is now 2021, and these communities have yet to see justice. With Ecuador, Canada, and the United States no longer being viable legal forums, there is no indication that these communities will receive their judgment. The damage is lasting, not only for the health of the indigenous community, but for the Amazon generally. The rainforest now emits more Greenhouse Gases (“GHG”) than it absorbs.21 Worse yet, the oil industry continues to invade communities in Ecuador—now attempting to move into Ecuador’s Yasuní National Park.22 Unsurprisingly, this region is also occupied by indigenous communities, living off the land and resources provided for them by their ancestors. For now, at least.

Corporate Capture

So, what is so wrong with the Ecuadorian system that this is happening to them? The hard truth is that this is not a region-specific issue. Chevron recently had a oil spill in the San Francisco Bay. Not sure what I’m talking about? That’s because most major news outlets did not report on it at all—including left-leaning favorites like the New York Times and the Washington Post. The coverage of the spill was mostly local (i.e., the San Francisco Chronicle) with only a few nationally read sources (i.e., ABC News) including the story in their daily news.23 This was not accidental—Chevron ensures that it controls the narratives being written. Some media sources simply did not mention the spill. Other sources reported that the oil spill did not “have an environmental impact.”24 To be clear, the spill was not insignificant as was claimed—it resulted in a Level 2 health alert from Contra Costa Health Services (the Levels start at 0 and go up to 3, making this the second-most-serious level), harming wildlife and marine life while ravaging through the ocean and washing ashore.25

At a closer look, the lack of accurate reporting is not surprising. Some news sources close to Chevron refineries are simply owned by the corporation, created to promote their narratives—for example, a quick glance at the Richmond Standard shows the key words, “Funded by Chevron,” right under the name of the site.26 With others, though, Chevron is more secretive with its control. A member of the board of the New York Times also serves on the board of Chevron and is the second-largest individual shareholder of Chevron.27 Not only does the liberal New York Times have Chevron ties, CNN shares Gibson Dunn lawyers with the corporation.28 Chevron has the resources to directly combat and control the narrative to shift blame. These resources are so vast that the corporation has put out paid advertisements on Google such as this one:

Figure 1: Chevron’s Paid Advertisement (Source: Google)

With a simple Google search of “Steve Donzinger,” I received an advertisement from the corporation itself about Donzinger’s legal failures. According to a climate-watch journalist, Gibson Dunn lawyers also threaten subpoenas if a company dares to report on Donzinger’s litigation, claiming the media company would be a co-conspirator after the fact of Donzinger’s “crimes.” Controlling media outlets in this manner ensures that the corporate-approved narrative is the only one out there. Even more concerning is that this story describes the misdeeds of just one company. Everything thus far has only been about Chevron. The problem runs deeply throughout the entire oil and gas industry.

The inability to receive unbiased, substantive reporting on ecological disasters is a classic symptom of capture. Traditionally, “capture” refers to the ability of an industry to control the agencies and government supposedly regulating it, rather than the other way around. This certainly applies here as well, as will be explored in the next section, but American society has moved beyond this narrow definition of capture. Not only are our government and media being controlled by industry, but, as a result, our own beliefs are captured. This is referred to as “deep capture” —an inability for one to determine what is true and best for himself. Of course, every person will see themselves as rational, but taking a step back, it is nearly impossible to remain acutely aware of the influence industry has over our beliefs. For example, without knowing that Gibson Dunn lawyers are strong-arming media companies, a rational citizen would see that the only reports on Donzinger’s case label him as a fraud and would thus come to that conclusion. The oil industry has taken its corporate power and used it as a weapon to control the government, the media, and the opinions of American citizens.

The Battle over the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge

A Deep History of Paid Destruction

The history of federally-controlled, public lands runs deep in the United States—dating back to 1781.29 In the modern era, public lands are controlled by the Bureau of Land Management (“BLM”), which was established in 1946. Public lands, though, are not just the national parks and beaches Americans love—they are home to approximately 6.8 million American Indians in Tribes.

Even though these lands are people’s homes and communities, there is still a significant push to privatize public land. This push comes in many forms—including outright privatization,30 selling the land to the states,31 or leasing the land for other designated purposes. A major force behind these efforts is the so-called “Energy Independence” movement. This movement existed long before the “energy independence” catchphrase came to the forefront of right-wing politics after 9/11.32 The battle-cry was designed to spark a fear of weakened “national security” if the United States did not begin producing more of its energy domestically. As a result, Congress passed legislation designed to increase domestic energy production, including the Energy Policy Act of 2005.33 This Act created various financial incentives and loan guarantees for energy production, as well as exempted hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) fluids from various environmental regulations and created a blanket of protection over massive energy companies from the Securities and Exchange Commission’s regulations and enforcement.34

The United States continues to subsidize oil and gas—with conservative estimates amounting to $20 billion per year going toward the fossil fuel industry. 80% of this goes directly to oil and gas.35

The cost of subsidies to the oil and gas industry does not account for the additional costs Americans are paying every year. There are vast negative externalities associated with the industry and its emission of GHG and pollution—including environmental, climate, and public health costs. These are estimated to total $5.3 trillion per year globally.36 These corporations are heavily subsidized and cause a massive amount of damage to the land, water, and air supposedly meant to be enjoyed by all. Once an oil corporation extracts what it needs from the public land it leases, it simply packs up and moves out. When the dollar signs end, the corporation walks away, leaving a destroyed ecological system in its tracks. It is estimated that cleaning up the roughly 94,000 oil and gas wells that currently sit on public lands, used or unused, would cost taxpayers $6.1 billion.37 We subsidize them, lease them our lands, and then clean up their messes.

The Tipping Point: Arctic National Wildlife Refuge

One piece of wilderness in particular has been in the sights of the oil industry for decades: the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (“ANWR”). Encompassing 19 million acres of protected land in Alaska, ANWR has a long history of protection, with the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act of 1980 specifically outlawing oil and gas drilling in nearly 80% of the refuge.38 However, one crucial region of ANWR is not protected—the Coastal Plain. The Coastal Plain is approximately 1.5 million acres, meeting the Beaufort Sea in northeastern Alaska. This region was separated from the rest when Congress, within the 1980 Act, instructed the Department of the Interior to study the environmental impact of oil and gas drilling on the Coastal Plain. The Reagan Administration’s Department of the Interior concluded that many species of wildlife “could” be harmed, but still recommended the Coastal Plain be opened up for leasing—prioritizing economic gain over these species of wildlife.39 The justification was made by citing the decline in domestic oil production, with the Department concluding that domestic oil was more important than ecological preservation. The study did not even mention the indigenous Tribes in a way more significant than just a footnote.40 Regardless of the Department’s determination that money is more important than human beings and wildlife, Congress continued to reject the proposal of leasing that region—voting almost 50 times against it.41

This all changed with the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) under the Trump Administration.42 Senator Lisa Murkowski, a Republican from Alaska, worked with the oil and gas industry to insert a clause in the Act to allow leasing.43 Murkowski, unsurprisingly, has received almost $750,000 from oil and gas donors between 2015 and 2020.44 Within TCJA (clearly not titled in a way that would indicate environmental legislation), Congress authorized oil and gas exploration, leasing, development, and production in the Coastal Plain. Not only was this authorized, TCJA specifically ordered the Secretary of the Interior to conduct at least two lease sales, each covering at least 400,000 acres, within 10 years of the Act. The first sale was to be held by December 2021, and the second by December 2024. By circumventing the regular lease sale process, the first lease was announced on December 3rd, 2020, and sold on January 6th, 2021—just two weeks before the inauguration of President Biden (who openly opposed leasing in the Coastal Plain).

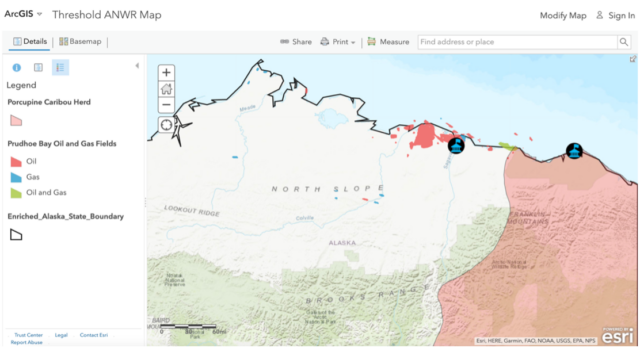

The region is home to the nomadic Gwich’in and their beloved Porcupine Caribou herd—a semi-migratory herd with which the Gwich’in travel. The Gwich’in are the Native Alaskan Tribe also living within the Coastal Plain, and they migrate with the caribou to stay alive. The two are interdependent on one another—and both rely on the land. Below is a map of current oil sites (in bright red) along with the region primarily occupied by the Caribou herd (pink overlay):

Figure 2: Current Oil and Gas Sites and Caribou Herd (Source: ArcGis)

There is some overlap between the existing oil and gas sites and the caribou herd. This map, though, does not account for the additional proposed drilling region, nor for the indigenous population. The new proposed region would extend further into the region shaded pink, representing the caribou herd. Below is a depiction of that extension:

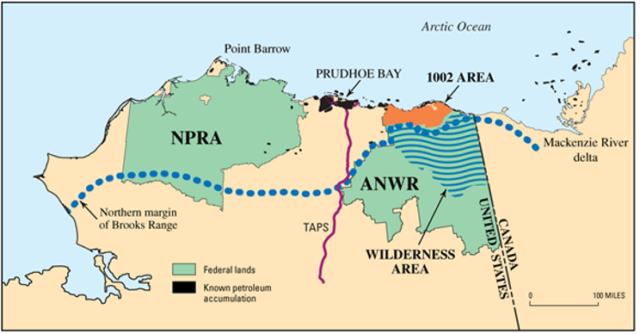

Figure 3: Proposed Drilling Region (Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration)

The black region labeled “Prudhoe Bay” is the region of oil and gas sites depicted in the prior map. The orange region represents the land proposed for additional oil and gas leasing, extending into the region the caribou and Gwich’in call home. Representatives from Alaska have made it clear that neither the Tribe nor its beloved caribou are of their concern. Representative Don Young, a Republican from Alaska, has openly stated that his priority is financial gain. Specifically, during a session, he said “it’s not about the environment or the caribou, it’s about economics.”45 This statement was made after a meeting he had with the Gwich’in.46 Unsurprisingly, Representative Young is also heavily financed by the oil and gas industry, receiving over $100,000 in campaign contributions in 2019 and 2020.47 Thus, it is in his best interest to represent the needs of the industry, rather than the people whose lives are in question.

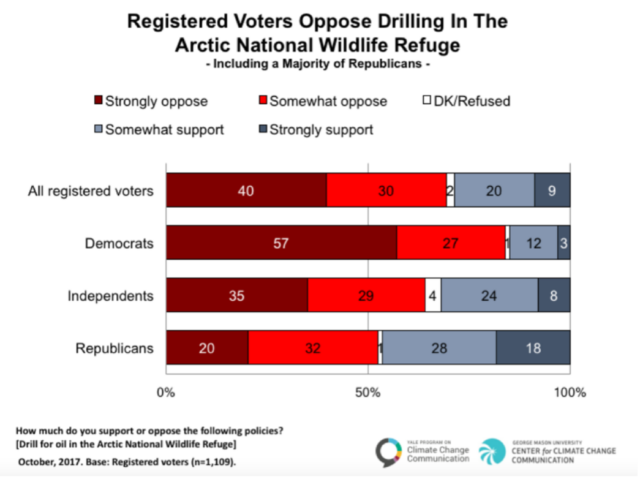

Representative Young and Senator Murkowski, while claiming to represent their constituents, are actually representing the industry financing them. The American people have already spoken on this topic—and the choice is clear:

Figure 4: Public Polling on ANWR Drilling (Source: Yale Program on Climate Change)

Yes, you are reading that poll correctly—even the majority of the Republican voters polled are against drilling. Specifically, 70% of the voting population is against drilling. As if that was not enough, the disdain for drilling in the region goes beyond voters. Not a single major bank is willing to finance the project. All six major U.S. banks—including Bank of America, Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan Chase, Wells Fargo, Citi, and Morgan Stanley—have openly refused to finance the project.48 Though this should have ended the project immediately, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (“OCC”) under President Trump put forth a new rule that prohibits banks from “discriminating against entire industries.”49 This rule was a direct response to banks refusing to finance the project, and has since been put on hold under the Biden administration.

By essentially purchasing politicians in the House of Representatives, the Senate, and the executive branch, the oil industry has been able to ensure that policies are beneficial to its interests. This exhibits the industry’s successful capture of our governmental institutions, and as a result, there are now virtually no political hurdles for the industry.

Profit Primacy

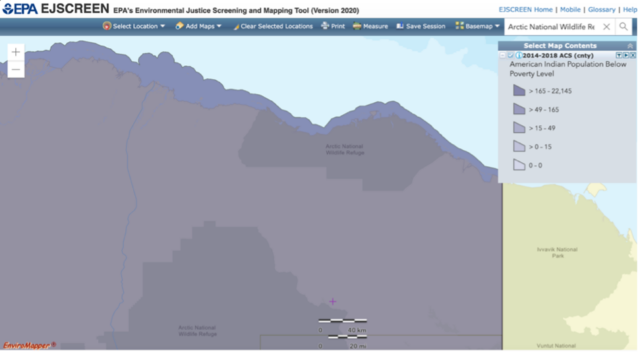

Even if there are no political hurdles, if the American people and their banks are adamantly opposed to drilling in ANWR, how is the oil industry able to ignore public backlash? The answer is simple—shareholder profits. Oil and gas companies, as well as most environmentally damaging industries, locate themselves in areas where lower socioeconomic communities reside. The land is cheaper, and the residents are not able to fight back. ANWR is no exception. Below is a map of the indigenous population below the poverty line, with the shade of purple determining the concentration of people below the line:

Figure 5: Concentration of Poverty (Source: EPA EJScreen)

There is a significant portion of the population living below the poverty line throughout the entire region. However, this concentration increases in the region proposed for drilling. This map is not specific to the Gwich’in and rather depicts the entire indigenous population in the region.

Though oil and gas companies must operate in regions where these resources are present, they also want to do so at the lowest cost possible to maximize their profits. Thus, regions occupied by those who do not have the resources to prevent land acquisition are deemed ripe for drilling. Corporations assert that this is just—as it is their duty to prioritize shareholders over others (referred to as “stakeholders.”) This is shareholder primacy—the court-affirmed theory that corporations have a fiduciary duty to their shareholders, which requires their main motivation to be in the interest of the shareholders.

The judicial system has upheld shareholder primacy as crucial to the corporate structure. Specifically, in Dodge v. Ford Motor Co., the Supreme Court of Michigan declared that a “corporation is organized primarily for the profit of the [shareholders], and the discretion of the directors is to be exercised in the choice of means to attain that end, and does not extend to the reduction of profits or the nondistribution of profits among [shareholders] in order to benefit the public,” relying on a wide variety of precedent to do so.50 Though decided in a Michigan state court, this case is fundamental to corporate theory, and therefore has been cited more than 1,500 times—including in U.S. District Court for Southern District of New York (the home of all things corporate).51

In translation, this means that corporations have received a court-approved mission to prioritize profits over all else, as profits are the only true benefit that shareholders are allowed to seek.

Shareholders retain interest in a corporation, receiving a share of the profits, without ever really engaging in corporate decision-making. Technically, shareholders have a number of methods that they may employ to engage in the corporate process, but they are notoriously passive. Rather than serving an actual purpose, shareholder votes are in place to serve as a source of legitimation, making outsiders view a corporation as a just entity because of its “corporate democracy.”52 In reality, though, these meetings often follow a script, and allow board members to alter the voting process to serve their own agendas.53 Thus, shareholders do not actually have a role in corporate governance, and therefore lack any incentive to participate in the votes at all. Keeping shareholders on the outside of true governance was reinforced by the judiciary in Pillsbury v. Honeywell, in which the court held that a shareholder seeking access to shareholder lists was not justified in doing so because his motivation was “social and political concerns, irrespective of any economic benefit … [which] does not entitle” him to the requested information.54 By resting its decision on the fact that the information sought was unrelated to financial gain, the court highlights that a shareholder’s only true role is receiving profits. Thus, connecting the dots, shareholder primacy translates to “profit primacy.”

Combining these holdings, we see that corporations must be structured “to serve their shareholders,” but shareholders cannot actually involve themselves meaningfully in corporate decision-making. The tension in the law is clear—corporations are able to hide behind a mask of “shareholder primacy,” while neglecting any wish of shareholders other than receiving a monetary benefit. Thus, rather than using their corporate power to ensure environmentally safe drilling that does not displace human beings, the oil industry prioritizes profits over all else.

Conclusion

So where does this leave us? Shareholders are not allowed to have any control in a corporation’s actions even though they own part of it. The government does not control industries because of the current system for campaign finance and the resulting government capture. The American people are virtually unable to receive unbiased, clear information, and therefore are suffering from deep capture, preventing them from drawing their own objective conclusions. This paints a bleak picture for the future of corporate control.

The dispute over drilling in ANWR is ongoing—the first lease has already been sold, but the Biden Administration is currently reassessing it. Since the leasing process was expedited and thus insufficient, there is a possibility that the lease may be cancelled. This would only be a temporary solution, though, as TCJA required the sale of leases, and that was passed “legitimately.” There are a few possible Congressional workarounds, but it is unclear how much could be done. The media coverage, unsurprisingly, is lacking.

The environmental and, quite frankly, human rights crisis in Ecuador began with drilling in 1964. It has been over 50 years and the ramifications are still being felt. The litigation is ongoing. America is on track to place the indigenous communities in Alaska in that position as well. If we sell more oil leases in Alaska, those communities are going to be pushed out. Worse yet, if they are unable to relocate, they will suffer the health and environmental impacts of drilling in the region. The Gwich’in rely on the wilderness for survival. But they are being ignored by Congress, and thus need more people to fight the sale of their land to big oil. The oil industry cannot be allowed to continue to operate in the legal grey—it is time to shine light on their unjust strategies.