The Tax Avoidance Problem

Taxes: The Lifeblood of the Modern State

In a speech in 2016, Christine Lagarde—then Managing Director for the International Monetary Fund—identified two ingredients of taxation for successful 21st-centruy economies:

“The first one is the ability of countries to generate robust government revenue. This is, of course, the lifeblood of modern states. This is what allows governments to provide public goods that support strong and durable growth. … The second ingredient … is international taxation. This is an essential means by which governments mobilize their revenues in a globalized economy.” 1

Lagarde, pointing out recent headlines by large corporations in exploiting loopholes to avoid paying taxes, called for a system that “discourages the artificial shifting of profits and assets to low-tax locations,” and “overly aggressive tax competition among countries.”2 Lagarde then plainly states that, “there is a widely shared recognition that too many multinational companies and wealthy individuals are ‘gaming’ a creaking system of international taxation that is no longer fit for the modern global economy,” recognizing that recent frustration with tax evasion and avoidance “reflects anger among many ordinary citizens around the world over rising inequality of income and wealth.”

Lagarde is correct in identifying two major offenders of tax avoidance through international taxation as wealthy individuals and multinational corporations. Rather than focus on the general fact that the wealthiest people around the world enjoy a different set of rules than everyone else, this paper focuses on multinational corporations and their unique ability to exploit international tax loopholes and international tax competition. Borrowing Lagarde’s poetic depiction of tax revenue as “the lifeblood of modern states,” it seems apparent that the current corporate tax policy in the United States has led to a hemorrhaging wound, preventing public investment into the same country that has allowed its corporations to thrive.

An example of this problem is emerging from the debate surrounding proposed legislation from the White House. The focus in Washington has shifted to President Biden’s American Jobs Plan. The proposed plan seeks to:

- Expand and repair the nation’s roads and bridges, as well as upgrade public transit systems;

- Remove all lead pipes from the nation’s drinking water systems, providing long overdue relief to many children and communities of color like Flint, Michigan;

- Improve the country’s electrical grid to prevent another deadly ice storm like the one in Texas earlier this year that turned off the State’s power;

- Provide affordable high-speed broadband to the nation, including the rural communities that lack access entirely;

- Build and improve schools, child care facilities, and facilities serving veterans;

- Create home and community-based care services, as well as more jobs and better wages for home care workers. 3

In accomplishing these goals and more, the plan will increase American manufacturing, provide job training, and create millions of jobs making it all happen.4 The President calls it a “once-in-a-generation investment in America.”5 The cost of this ambitious public investment into some of the nation’s most critical areas of need? $2 tillion. 6

As the Biden Administration pushes forward with its plan, a familiar refrain from President Biden’s time as Vice President is ramping up in volume: the nation cannot afford public spending on this policy because it has too much debt. Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell signaled Republican opposition to the plan because it would cause “massive tax increases and trillions more added to the national debt.”7 The Biden Administration has proposed offsetting the cost for the plan with an increase in the corporate tax rate over 15 years, with a focus on “multinational corporations that earn and book profits overseas.”8 In doing this, Biden would increase the corporate tax rate to 28%, a 7% increase after the 2017 Tax Cut and Jobs Act (TCJA).9 Those in opposition have painted this corporate tax increase as catastrophic for the economy,10 while business groups—seemingly fearing Democrats pushing ahead if Republicans do not negotiate in good faith—have pressed Republicans to accept a bipartisan deal that avoids an increase in corporate taxes.11

Corporate Taxes: The Most Popular Tax in America

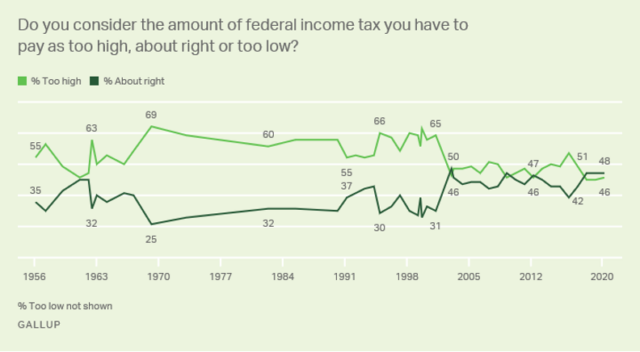

Taxes are always a hot topic in American political discourse. The lowering of taxes for the working and middle class is a point constantly repeated on campaign trails. Since Gallup started tracking in 1956, Americans have only recently considered federal income tax rates to be ‘about right’ than ‘too high.’ This first happened in 2003—which is the high-water mark for support of the current rate at 50% feeling it was ‘about right’—then in 2009, 2012, and every year since 2018, the year after the TCJA.12 The amount of respondents who felt the federal tax income rate was ‘too low’ has never been higher than 4%, which happened for the first time in 2011.13

Figure 1: American Opinion on Federal Income Tax Rate Over Time (Source: Gallup)

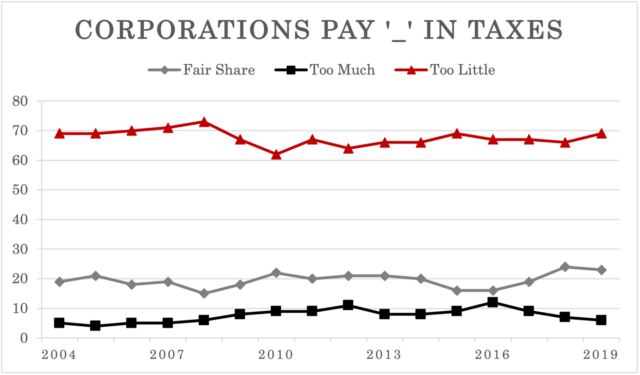

While the appropriate rate of the federal income tax is contested, the poll’s data on corporate taxes is quite clear. Since Gallup began tracking how Americans felt about corporate tax rates in 2004, the amount of Americans that feel corporations pay too little in federal taxes has never been lower than 62%, though it is often closer to 70%.14 The second highest response—just 24% of respondents at its highest—is that corporations pay their ‘fair share’ in federal taxes.15 Just 4 to 12% of Americans felt that corporations paid too much in taxes.16

Figure 2: American Opinion on the Federal Corporate Tax Rate Over Time (Source: Gallup)

More recently, an April 2021 Pew Research Center survey found that 59% of Americans were ‘bothered a lot’ by the feeling that some corporations did not pay their fair share in taxes. 17 22% were somewhat bothered, while only 18% were not bothered much or not at all bothered.18

With seemingly broad public support behind increasing the share that corporations pay in taxes, it is puzzling to see opposition to passing legislation that would do exactly that. Nevertheless, the reluctance to increase corporate taxes remains strong.

Multinational Corporations and the Patchwerk Tax System

Tax Havens

Increasing the corporate tax rate would increase revenue and help alleviate some of the burden of the individual taxpayer, but it fails to address an increasingly common problem identified by Lagarde in her 2016 speech: corporate tax avoidance.19 Tax avoidance is a tactic, employed by companies such as Apple, that takes advantage of a patchwork system of different taxation schemes across the globe to avoid paying taxes on its earnings. Despite being a publicly traded American corporation, much of Apple’s earnings technically flow through Ireland’s jurisdiction using a holding company20.21 Ireland’s tax law determines tax residence by where the company is managed and controlled—for Apple, that is the United States—while United States tax law is based on where a company was organized—for Apple, in Ireland—creating a loophole in which Apple avoids taxes on its earnings in the United States entirely, while paying a significantly lower rate in Ireland.22 Despite this, Apple Inc., the publicly-held corporation, is incorporated in California, traded in the United States, and benefits from American corporate law.

Ireland is not alone in offering alluring tax policies to attract multinational corporations to invest in their country. International tax competition has created numerous ‘tax havens’ that incentivize corporations to house earnings within their country so that they can earn more revenue than they would have otherwise by undercutting countries that tax corporations at a higher rate.23 International tax competition has created a problem in which developed countries face a fiscal crisis due to the erosion of their corporate tax base that “no amount of change in income taxes is likely to produce sufficient revenue” to replace.24 So, while President Biden’s increase on the corporate tax rate will likely be popular with Americans and even generate some revenue, it alone is unlikely to effectively supplement the lost revenue base from corporations offshoring their earnings in tax havens.

What does the law have to say about tax avoidance? Doesn’t the IRS go after everyone that does not pay taxes? It is important to note that tax avoidance and tax evasion are two distinct legal concepts. Section 7201 of the Internal Revenue Code criminalizes tax evasion, stating:

Any person who willfully attempts in any manner to evade or defeat any tax imposed by this title or the payment thereof shall, in addition to other penalties provided by law, be guilty of a felony and, upon conviction thereof, shall be fined not more than $100,000 ($500,000 in the case of a corporation), or imprisoned not more than 5 years, or both, together with the costs of prosecution. 25

While it may seem that creating a holding company to keep earnings offshore in order to avoid taxes would fall under a ‘willful attempt’ to ‘evade’ a tax, the crime requires proving (1) that an unpaid tax liability exists; (2) that the defendant took an affirmative act to evade a tax; and (3) that the defendant had specific intent to evade a known legal duty to pay. It is unquestionable that Apple chose Ireland as a tax haven for the reason of not wanting to pay American taxes on earnings. The reason why this avoidance is legal is because it does not meet the first requirement. Apple is not evading the payment of a tax they are liable for—Apple is avoiding the tax liability in the first place by putting its earnings outside the jurisdictional reach of the United States.

National Solutions to an International Problem

While Lagarde is correct that people are increasingly growing frustrated with corporations not paying their fair share in taxes, it is not a new phenomenon by any means. Tax havens began to develop at the end of World War I and began really taking off during the 1960s. 26 Apple’s use of Ireland as a tax haven started in the 1980s, pioneering the tax structure known as “The Double Irish,” variations of which have since been used by corporations like Google, Microsoft, and Pfizer.27 The United States has made efforts to address the tax avoidance problem of multinational corporations, but the results have largely been disappointing.

In 2004, Congress—hoping to stimulate job growth domestically, which extensive lobbying by corporations suggested would be the result—passed the Homeland Investment Act (HIA) allowing corporations to bring offshore income at a reduced tax for two years.28 The HIA succeeded in bringing capital back to the United States, but it allowed the avoidance $3.3 billion in taxation.29 The HIA did not result in significant job growth or domestic investment, but instead lead to a near 1:1 ratio between dollars brought in and payouts to shareholders.30 It also incentivized the continued use of offshoring wealth to cash in on the next tax holiday.31 When another repatriation tax holiday was considered by Congress in 2011, a lobbying group named “The Win America Campaign”—which notably included Apple and Microsoft—spent $760,000 on persuading legislators to pass another bill. 32 After a year of bipartisan reluctance, the group suspended lobbying, though it remained adamant that repatriation and tax reform was a top priority.33

Congress recently attempted to address tax avoidance in 2017 with the TCJA. The Act shifted American corporate tax policy from one that taxed worldwide income brought back to the United States to a more modern and common territorial system that does not tax income outside of the United States.34 The TCJA addresses tax avoidance in two ways. First, it implements taxes that discourage the use of tax havens by requiring a rate of 10% of foreign profits be paid at some point.35 Second, it provides subsidies that incentivize having property and jobs in the United States.36 Additionally, the TCJA provided another repatriation tax holiday with reduced taxes for foreign assets brought back to the United States over the next eight years as a “transition period.”37

One problem undercutting the new tax system’s success in preventing tax avoidance is that it looks at foreign income for multinational corporations in the aggregate instead on a country-by-country assessment. This actually further incentivizes the use of tax havens because it allows taxes a corporation pays in one country to shield the profits made in tax havens from the 10% minimum tax rate. Estimates suggest this will cost the United States $1.5 trillion over 10 years.38 Far from ending the use of tax havens like Ireland, the TCJA had the opposite effect—corporations like Apple, Amazon, Facebook and Google are actually expanding their presence in Ireland.39

Corporate Law and Tax Avoidance

The Race to the Bottom

The wealth and power of corporations as legal entities places them in a position to leverage their value against countries themselves. In addition to spending vast amounts lobbying Congress for favorable policy, the threat of moving jobs and the tax revenues to a country with a lower rate has created an international race to the bottom.40 Corporations are uniquely capable of exploiting international tax competition through their immense wealth and global reach. The reason tax competition even exists is because the countries acting as tax havens know that they can land corporations if their tax policies are tailored to them.

A rational person must ask why would a corporation not exploit countries willing to craft a tax policy just for the corporation? Why would a country seeking revenue to support itself and its citizens not bend over backwards to attract a steady source of revenue? It is mutually beneficial for the country and the corporation, but fails to take into account the taxpayers the corporation leaves behind. Corporations unique wielding of wealth and power beyond that of even many countries that should cause concern. This problem affects not only American citizens, but the entire world.

This should not be surprising, however, given the historical race to the bottom brought on by corporations within the United States. The United States was once very restrictive in allowing the creation of corporations due to widely held opinion about their negative impact on the public.41 At the end of the 19th century, New Jersey liberalized its corporate law, which started the race to attract corporations.42 States quickly realized that their restrictions on corporations would be circumvented by the option to incorporate in States that had more favorable policy, which would lead States that failed to reform their corporate law to miss out on potential tax revenue.43 Delaware soon followed New Jersey’s lead, eventually overtaking New Jersey as the favorite state of corporations after then New Jersey Governor Woodrow Wilson made New Jersey corporate law more restrictive.44 Since then, Delaware has maintained its favored status by corporations, never once allowing another State to take a lead in the race.45

A Feature, Not a Bug: Tax Avoidance and the Dodge “Mandate”

Profit Primacy

Another issue arises from corporate law and its construction of how corporations should be managed. In order to protect shareholders from self-interested managers, corporate law has established fiduciary duties that management owes to the shareholders. These duties are simply distilled to one simple rule: maximize profit. Through this understanding, tax avoidance can be just another means of profit maximization in which corporate management is obligated to participate. Eric Chaffee’s 2019 article in the Washington & Lee Law Review explains: “Many corporate managers will argue that their fiduciary duties to the corporation and its stockholders require them to engage in tax avoidance as a means of achieving profit maximization. They either directly or indirectly derive this requirement from the classic corporate law case, Dodge v. Ford Motor Co.” 46 This “Dodge Mandate” formalizes the duty to achieve profit maximization, and by extension, every legal means of achieving it.

This framing of the issue presents corporations not as dispositionalist actors choosing to engage in tax avoidance out of their own desire for profit, but rather as helpless participants in their situation, having no choice in the matter because they must serve the shareholders. The Dodge Mandate to maximize profits ignores a key group outside of corporate management and shareholders: stakeholders. Stakeholders lack the same legal protections provided to shareholders as stakeholders do not own shares of the company. When a corporation avoids taxes, the stakeholders are taxpayers and welfare recipients. Programs the support the most vulnerable in society that must either displace the loss of tax revenue with a larger burden for individual taxpayers or through cuts to quality or eligibility of programs that stave off poverty, homelessness, and hunger. This can be seen happening in Republican counterproposals to the Biden Administration’s infrastructure and jobs plan that propose a quarter of the amount in spending, diminishing the quality and scope of the original proposal. 47

Despite this guiding value of shareholder primacy, corporate law often fails to give shareholders any meaningful control over corporate decisions. For instance in Pillsbury v. Honeywell, an effort by a shareholder to stop the production of munitions being used in Vietnam was stopped by the court when it denied access to the contact information of other shareholders as well as Honeywell’s documents related to manufacturing of weapons and munitions.48 Furthermore, the cost and difficulties of organizing a large group of shareholders leads to a collective action problem in which shareholder votes are typically a rubber stamp on management’s desires.49 In practice, the idea of shareholder primacy is replaced by the reality of profit primacy.

Questioning Dodge

Corporate law’s legitimizing of the tax avoidance through an argument that the Dodge Mandate requires it illustrates a deeper problem. It is important to note that not everyone agrees that this understanding is appropriate within corporate law. Professors Chaffee and Davis-Nozemack argue that the business judgement rule’s allowance of discretion to corporate management prevents the requirement of tax avoidance by the Dodge Mandate.50 But this failes to consider that managers want to engage in tax avoidance. While a may not be required to avoid taxes under this theory, it is highly unlikely that discretion would change the result.

Professor Chaffee suggests a transformation within corporate law underlying purpose:

“By understanding the corporation as a collaboration between the government and the individuals organizing, operating, and owning the corporation, the impermissibility of aggressive corporate tax avoidance becomes apparent.” 51

This change in understanding would be a departure from the profit maximizing script that currently legitimizes corporate law. It would help provide a basis for which it becomes illegitimate to reap the benefits of the United States while not paying back the stakeholders—the public.

While corporate law’s Dodge Mandate may present a legal command for maximizing profit, the justifications go further. Corporate legal scholars argue that profit primacy does not just protect the shareholders—it maximizes the welfare of stakeholders and society. Corporate law reasons that while it may not be the place to answer questions of wealth distribution or to protect stakeholders, you do not have to worry because “no one need be made worse off by the corporation’s having a single goal of profit maximization . . . corporate resources can still be diverted to these governmental activities . . . Because governments can tax both corporations and their shareholders.”52 But if that is the case, it seems dubious to assert that tax avoidance is maximizing the welfare of society as a whole—taxes are the lifeblood of the modern state.

Law & Economics and Tax Avoidance

It is important to recognize Law & Economic’s53 place in corporate law and the law as a whole. As a theory, it gives a guiding principle on how to determine legal rules—choose economic efficiency at every turn and questions about distribution to a more efficient tax and transfer system.54 This theory serves at the launch pad for corporate law55 and explains the logic of profit maximization as a duty to shareholders and the best way to maximize societal welfare.56 The primary explanatory analogy is growing the “pie” so that everyone receives a bigger “slice.”

‘Markets Good, Regulation Bad’ is Easy, but Problematic

Another premise of Law & Economics that finds a home in corporate law is the preference for markets and as little regulation as possible.57 The premise behind this is a fear of capture—that corporate power will capture regulators and choose regulations that benefit its control of the market and extraction of wealth.58 But with corporate law already oriented toward markets and profit maximization, the last four decades have only demonstrated that without regulation, corporate power will still continue to benefit itself as much as it can. Taxation is certainly not a regulatory issue in the traditional sense, but that has not stopped it from being captured—through the use of lobbying and the threat of the corporations moving operations to lower tax rate jurisdictions—to serve not the interests of stakeholders and society, but of the corporations themselves.

Additionally, corporations are in a position to dominate corporate tax policy specifically. This is not an issue that ordinary citizens spend time thinking about. When they are balancing multiple aspects of their life like work, school, family, and finances, people are more concerned with the problems immediately ahead of them than they are the nuances of corporate tax policy. There certainly is not a grassroots political movement behind sweeping reform for corporate tax policy, even despite a consistent two-thirds of Americans supporting corporations paying more in taxes in Gallup polls the last two decades.59

Where is the Tax and Transfer System?

The whole of Law & Economics is seemingly premised on a grand bargain of always choosing growth over distributional concerns with the understanding that a tax and transfer system can be relied on to efficiently redistribute wealth so that everyone benefits from the larger ‘pie.’ If corporate law is going to subscribe to this system—choosing growth from unrestrained markets over regulation that protects stakeholders and society—surely tax avoidance cannot be a requirement under the guise of protecting shareholders, let alone be tolerated in any sense. And yet, the reality is that tax avoidance for the largest American corporations is the standard as Congress makes continuous half-measures to create a system that generates tax revenue without running off corporations to tax havens.

Conclusion

In a globalized economy, corporations will move capital and their tax liability to countries that provide the most lucrative and profit maximizing policies. Because countries with smaller economies need to attract this investment, they engage in a race to the bottom to become corporate tax havens. As a result, the United States and other developed countries are losing their corporate tax base and, subsequently, fail to support investments in public programs, lose legitimacy, and are seeing exacerbated wealth inequality.60 While corporations benefit from the laws and support of the United States, the stakeholders—ordinary citizens—do not receive the benefits from organizing society to benefit corporations when corporations can so easily escape tax liability. Corporate law legitimates and may even demand corporate tax evasion by justifying it as a fiduciary duty to maximize profits, but it does not have to. We could adopt a different understanding of corporations as suggested by Chaffee.61 It remains unclear if that can be accomplished or if it would, by itself, be enough to overcome corporate power in shaping the corporate tax policy and corporate law in general.