INTRODUCTION

In February of 2011, the German carmaker Volkswagen (VW) posted a video advertisement to YouTube in advance of the upcoming Super Bowl. The spot, which depicted a small boy dressed in a Darth Vader costume who went around attempting to use “the Force” on everyday household objects, was designed to highlight the “remote start” feature in VW’s all-new 2012 Passat.1 The automobile itself received solid but not exceptional reviews, carving out a niche as a “competitive car for families” with “some green cred” thanks to its powerful, fuel-efficient diesel option.2 The ad, however, was an absolute sensation, quickly becoming the most-viewed video advertisement of all time.3 Although audiences initially struggled to identify him, it also made something of a celebrity out of its helmeted star, six-year-old actor Max Page.4 As things turned out, he may have been lucky to have been wearing Vader’s mask.

Over four years later, in September of 2015, the corporation released a very different video. In it, then-CEO Martin Winterkorn apologized to VW’s customers, employees, and the public for what he referred to as “irregularities” in the automaker’s diesel engines.5 The video was prompted by a widely publicized letter from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) which revealed that engines in over eleven million vehicles, including the 2012 Passat and other models produced by VW and its subsidiaries Audi and Porsche, employed a so-called “defeat device” to cheat regulators’ emissions tests.6. Within two months of the letter’s publication, the value of shares in VW decreased by a whopping 46% ($42.5 billion), prompting lawsuits from the corporation’s shareholders and creditors.7 Altogether, VW has been forced to spend over $30 billion on legal fees, fines, and settlements relating to the scandal, with various civil and criminal cases still pending across Europe and the United States.8

Today, the so-called “Dieselgate” scandal is widely derided by both academics and the general public. However, subsequent investigations have revealed that the problem of emissions cheating is not limited to VW alone, with nearly every major carmaker linked to the practice in some form.9 The prevalence of such harmful misconduct suggests that Dieselgate is due for a re-examination. While many of the scandal’s root causes suggest that VW is an outlier among car corporations, others reveal deeper problems lurking within the fabric of the global auto industry and, more broadly, corporate law. Only with this wider context is it finally possible to outline real, sustainable solutions to the systemic problem of emissions cheating.

THE PHANTOM MENACE: PUBLIC HEALTH AND ENVIRONMENTAL HARMS

It is virtually impossible to measure the true impact of VW’s cheating. However, scientists can lay out a relatively detailed causal chain of events connecting VW’s actions to worsening public health and the environment. That chain starts in the company’s diesel engines, which produced three major pollutants: carbon dioxide (CO2), refined particulate matter (PM2.5), and nitrogen oxides (NOx). CO2 is the most widely known, although most people are also familiar with PM2.5under its common name: soot. NOx, meanwhile, refers to a lesser-known family of gasses which play a key role in the production of ground-level ozone, the main ingredient in smog.10

While VW’s engine was designed to limit all three types of emissions, it could not comply with U.S. emissions standards without becoming incredibly expensive to build and maintain. As a result, VW developed software which could tell when the car was being tested by regulators. When activated, the system would instruct the engine’s “NOx trap” and other countermeasures to function normally, working full-time to keep the car’s NOx emissions below the legal limit. At all other times, it deliberately impeded such countermeasures. While this increased the engine’s NOx emissions, it also reduced its creation of CO2 and PM2.5. In practical terms, this boosted the car’s fuel economy and reduced wear on the engine’s PM2.5 particle filters, creating convenience and saving money for VW and its customers.11 In every sense of the word, VW made its engine more efficient.

Figure 1: Volkswagen of America print advertisement (Source: New York Attorney General’s Office12).

However, this efficiency had hidden costs. While exposure to each of the three pollutants has been linked to a variety of negative health effects, an informed public would not have made this particular trade-off.13 NOx has been linked to a variety of health issues, including asthma, bronchitis, reduced lung function growth, and other cardiorespiratory diseases.14 Young children and those without access to healthcare are particularly vulnerable to these conditions, which have only become more serious in light of the COVID-19 pandemic.15 In addition, excess NOx may react with the environment to form PM2.5 outside of the engine, where it cannot be contained by the car’s filters. These particles replicate the worst health effects of NOx and also cause cancer.16

Of course, humans are not the only entities harmed by these chemicals. According to the EPA, NOx contributes to global warming and has a massive effect on a wide variety of ecosystems.17 On land, it is particularly damaging to vegetation, draining soil of its nutrients and directly attacking leaves and needles. These changes subsequently spill out into the wider forest ecosystem, impacting the animals which rely on plants for food and shelter. At sea, NOx can also increase the acidity of surface water to uninhabitable levels, eliminating some species entirely. These changes are particularly harmful around the coasts, where a NOx–driven process known as “eutrophication” has destroyed numerous marine populations. Buildings and even the cars themselves can also be impacted by high levels of NOx, which causes structures to wear down at quicker speeds.

According to estimates made in the aftermath of the scandal, VW’s engines produced anywhere from 3,400 to 15,000 metric tons of NOx per-year over the required limit.

In Europe, where the cars were more prevalent, up to 5,000 premature deaths may have been averted simply by complying with the EU’s relatively lax diesel emission limits.19 Compliance may also have reduced permanent damage done to the coastlines and ecosystems of the Netherlands, France, Italy, and Germany by half.20

Ironically, one of the people put most at risk was the “Little Darth Vader” himself. In real life, actor Max Page suffers from tetralogy of Fallot, a congenital heart defect which has so far caused him to undergo thirteen heart surgeries.21 Side effects from the disease, including a bout of endocarditis which put him in the hospital for thirty-two days in 2017, may be exacerbated by exposure to PM2.5.22 As a resident of the coastal and famously smog-prone city of Los Angeles, Max must also live with the effects of excess NOx emissions on land and water for years to come. Today, Max uses his celebrity to advocate for increased government spending on child healthcare.23 The car he became famous for selling, meanwhile, may have done more than he ever could to create new advocates for his cause.

ATTACK OF THE CLONES: PROBLEMS AT VW

Employees

The aftermath of almost every corporate scandal of this magnitude is consumed by one question: how did this happen? Here, the problem was quickly traced back to a 2006 meeting of a small group of employees in VW’s Wolfsburg headquarters.24 In testimony before Congress soon after the scandal broke, Volkswagen of America CEO Michael Horn emphasized that the device’s development “was not a corporate decision,” pointing out that “no Board meeting or no Supervisory Board meeting” authorized it and suggesting that it was devised and installed solely by “a couple of software engineers.”25 Through these remarks, Horn absolved the corporation and the rest of its employees from blame.

However, evidence soon emerged that knowledge of the device extended much further. VW’s head of motor development attended that first meeting back in 2006, and over the years numerous other executives worked closely on projects involving the device.26 Following a six-year internal investigation, VW’s board reversed its previous position and announced plans to seek damages from former CEO and Chairman Martin Winterkorn and former Audi boss Rupert Stadler for “breaches of the duty of care.” To this day, however, it maintains that no other manager violated their duties in connection with the scandal.27

Outsiders largely disagree with this limited view, pointing instead to deeper issues in VW’s corporate culture.28 Proponents of this theory argue that the emissions scandal is merely a large-scale example of the classic “agency problem.” According to them, VW’s agents (its executives, managers, and workers) were collectively incentivized to behave in a way which harmed VW’s principals (its shareholders), who lacked the capacity or resources to supervise their agents’ actions.29

In the years prior to Dieselgate, VW executives repeatedly incurred liability and bad press through a variety of infractions ranging from the theft of trade secrets to, most sensationally, the misuse by certain executives of over five million euros in company money on self-dealing, prostitutes, and gifts to a Brazilian mistress.30 While the executives’ motivations ranged from self-enrichment to a desire to improve VW’s performance, all ultimately harmed the corporation and its shareholders. Winterkorn’s own resignation letter implicitly acknowledged the existence of this problem, declaring “Volkswagen needs a fresh start – also in terms of personnel.”31

Winterkorn’s management team was also known for instilling a culture so ruthless and dictatorial that one former employee described it as being “like North Korea without labor camps.”32 This culture permeated even the lowest levels of the company, including around the 2012 Passat. At an October 2011 marketing conference in Washington, D.C., a VW team delivered a presentation revealing the process behind their hit Super Bowl ad.33 One slide in particular stands out:

Figure 2: Volkswagen of America marketing presentation (Source: Direct Marketing Association of Washington).

The presentation goes on to outline VW’s “ambitious” and “unprecedented” sales goals, emphasizing the need to “fundamentally rethink convention” in order to boost sales from 10,000 cars per-year to the same amount per-month.

In retrospect, given the intense pressure to succeed and regular rule-breaking among senior executives, it is understandable how so many employees were driven to accept the defeat device. Concerningly for VW’s shareholders, this willingness remained intact even in the face of repeated warnings that the company could face catastrophic liability if such a device was discovered.34

Shareholders

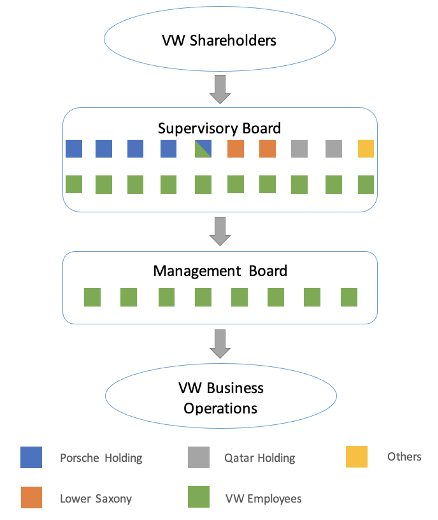

As it turns out, however, shareholders were a key part of the company’s problem. To understand why, it is first necessary to examine VW’s operating structure. Like all Aktiengesellschaft (German publicly-listed companies), VW is run by a Management Board, which handles day-to-day company operations, and a Supervisory Board, which appoints and can discharge members of the Management Board.35 And like all Aktiengesellschaft of its size, ten seats on the twenty-seat Supervisory Board are reserved for representatives of the company’s employees, with the other half elected by shareholders.36 This structure appears to reinforce the agency problem by empowering employees at the expense of shareholders, who typically elect the entire board.37

Figure 3: VW shareholder structure as of December 31, 2020 (Source: Unknown).

Board elections at VW are further complicated by an unusual separation of share ownership and voting rights. This “dual class” structure ensures that while many different investors own shares in the company, its Supervisory Board is almost entirely dominated by a select group. The most powerful shareholder is Porsche Automobil Holding SE, which controls five Supervisory Board seats and a majority of voting power. This “holding company” administers the combined interests of the Porsche-Piëch family, the descendants of Volkswagen inventor Ferdinand Porsche. Another investor dating back to the founding is the German state of Lower Saxony, which retains 20% voting power, two board seats for its political leaders, and special veto privileges.38 Finally, in recent years the rulers of Qatar have amassed 17% of votes and two board seats. As a result, the company is almost entirely controlled by these few shareholders and their hand-picked employees.

Figure 4: VW board structure as of December 31, 2020 (Source: Unknown).

VW has been governed by versions of this “controlled” structure since its privatization in 1960.39 In contravention of best practices, this has sometimes led to a blurring of the line between managers and shareholders. Nowhere was this more evident than with Ferdinand Piëch, a longtime VW executive and a grandson of Ferdinand Porsche.40 In his evolving capacities as a shareholder, heir of the founder, CEO, and chairman of the Supervisory Board, Piëch wielded unparalleled power. Often, he was able to unilaterally dictate the direction of the company through a combination of his managerial authority, personal voting share, and close ties with the employees and local politicians who sat on VW’s boards.41 His management style, which endured through his protégé Winterkorn, is also cited as the source of its infamous culture.42 Under his authoritarian rule, each new manager mimicked the last, failing to address or rectify the problem of the defeat device.

Corporate Solutions

To prevent another Dieselgate, therefore, VW needed to change its culture and import stronger corporate governance practices. Suggestions included unifying share ownership and voting rights, installing independent directors on the Supervisory Board, adopting new compliance and whistleblowing procedures, hiring new managers, and even stripping the Porsche–Piëch family of their majority control.43 However, such proposals were initially ignored or resisted, as the family’s continued dominance and the 2017 departure of the firm’s reform-minded head of compliance indicate.44 Not coincidentally, the company continued to struggle. These failings were exemplified by VW’s proposed fix of the 2012 Passat, which the EPA rejected in late 2017 after yet another failed emissions test.45

Following its 2017 settlement with the U.S. government, however, VW began to improve. The company has since received regulatory approval for all Dieselgate-related engine modifications and completed a rigorous three-year monitoring program.46 Although the Porsche-Piëch family remains influential, the prior management team has departed and the company’s culture has been transformed by new training and compliance procedures. VW as a whole seems well on its way to becoming, as their court-appointed monitor put it, “a different and better company.”47

REVENGE OF THE SITH: CAPTURE AND CORPORATE POWER

While this narrative is compelling, it ultimately fails to account for a key element of Dieselgate: the consistent cheating of VW’s global competitors, each of which is governed by a different structure and culture. For example, Daimler retained the employee board representation of a typical Aktiengesellschaft without the state involvement or close family control present at VW.48 Conversely, Fiat Chrysler was dominated by its founder’s descendants but incorporated under a shareholder-friendly Dutch structure that did not require board-level employee representation.49 In the wake of Dieselgate, both corporations reached settlements with the EPA over the use of defeat devices.50 Tests across Europe also continue to show that ambient concentrations of NOx remain higher than reported emissions, a discrepancy which suggests that defeat devices might still be used.51

There are three logical explanations for this prevalence. First, corporate governance may not have any impact on a carmaker’s propensity to cheat. Alternatively, the corporate governance of each carmaker may be individually flawed in a way that incentivizes cheating, with VW being a particularly egregious example. While this theory has more merit than the first, the contextual evidence ultimately favors a third possibility: that emissions cheating is incentivized by the corporate form itself. In this light, VW is not merely an outlier but rather a harbinger of broader issues in the global corporate system.

Every emissions-cheating carmaker is a multinational corporation, an entity that operates with the ultimate goal of increasing shareholder value by maximizing profit.52 Individually, each carmaker worked to achieve this aim by violating emissions regulations. Collectively, they did the same by shaping laws, regulations, and even public opinion on emissions to limit the potential for detection or punishment. While this second strategy was entirely legal, it enabled and ultimately served the same function as the first, increasing the carmakers’ profits and enriching its controlling shareholders and executives at the expense of the wider group of “stakeholders,” including governments, consumers, and communities around the world.

At its heart, this theory relies upon the concept of regulatory capture, which holds that regulators tend to design and operate rules primarily for the benefit of the largest corporations in the industry they are charged with overseeing.53 In Europe, this end was achieved via the Competitive Automotive Regulatory System for the 21st Century (CARS 21) advisory group, an industry-dominated body which pushed the EU to deregulate the emissions testing process.54 Within those regulations that remained, the EU left a series of loopholes allowing carmakers to cheat the system without even disclosing that they were doing so.55

In America, meanwhile, the effect was more subtle. While the EPA’s emissions regulations remained relatively stringent, close industry ties and limited funding led to internal pushback against the introduction of additional testing, including the very tests that caught VW.56 Similar forces also contributed to a series of lenient enforcement actions against VW’s competitors, as carmakers who were caught cheating typically cooperated with their friends in government to keep fines relatively low. Notably, those same authorities chose to seek stronger penalties against VW only after it emerged that the company had deliberately chosen to mislead them.57

Capture was not solely limited to the regulatory sphere, however. In particular, German politicians at local, national, and international levels of government continued to advance the aims of the auto industry in the wake of the scandal, fighting to keep emissions loopholes intact and working to approve the cheapest form of VW’s engine fixes for use across the EU.58 In return, the wider industry served as an important source of national pride, tax revenue, and post-government career opportunities.59 For similar reasons, some commentators suspected local prosecutors of leniency when dealing with senior VW management throughout their various scandals.60

Capture also extended to the carmakers’ shareholders. Although many of VW’s owners disliked the scandalous headlines, they continued to publicly support a governance structure and team that made it the most valuable company in Germany and, briefly, the world.61 To this day, BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager and a significant shareholder, recommends against discharging VW boardmembers who were in power at the time of the scandal. Its stated rationale? “[H]olding those individuals accountable.”62

Similarly, even ordinary German citizens remained captured by VW despite being among the most harmed by the company’s cheating. Some decried the hypocrisy of America, the world’s biggest polluter and Germany’s economic rival, enforcing environmental standards against them. Others highlighted the prevalence of cheating across different car brands and emphasized the availability of non-cheating VW models, redirecting blame from the carmaker to its competitors and consumers. As one reporter put it, “ask them to [choose] between the family pup and the Passat, and the answer might surprise you.”63

All of this was underpinned by a global corporate legal system that actively and increasingly sought to conform law to the doctrine of shareholder primacy. By 2005, even the famously stakeholder-oriented Germany had reformed its corporate governance regime to further protect shareholders.64 Nowhere were the distributive dangers and illusions of this shift more evident than at VW itself. In 2007, formal government restrictions on VW share ownership were overturned by the European Court of Justice. Ostensibly, this verdict protected European citizens’ fundamental right to “the free movement of capital” and created an opportunity for “other shareholders to participate in the company.”65 In practice, however, it merely paved the way for a further consolidation of Piëch’s power at VW, thereby ensuring the defeat device would remain undiscovered for years.66

Viewed in this light, the current corporate system presents a new, more deadly agency problem. The planet’s agents (its corporations, governments, citizens, and legal institutions) have been collectively incentivized to behave in a way likely to harm the planet’s principals (all living things), who lack the capacity or resources to supervise their agents’ actions. As with VW’s previous management team, problems will persist unless a change is made.

A NEW HOPE: SYSTEMIC SOLUTIONS

The prevalence of capture leaves those looking for a solution with few good policy options. Some in the United States and German governments have sought to aggressively prosecute executives and employees.{{Ewing, supra note 11, at 224-45; Memorandum from Sally Q. Yates, Deputy Attorney Gen., U.S. Dep’t of Justice, to All U.S. Att’ys et al. (Sept. 9, 2015), https://www.justice.gov/dag/file/769036/download.

}} The glacial pace of the case against Winterkorn and other senior executives, however, highlights the drawbacks of this approach. More specifically, it demonstrates the enduring danger of capture, the immense resources required to pursue enforcement, and the various ways in which corporate funds may be deployed to reach preemptive settlements.67 To put it bluntly, the system remains rigged.

To change that, governments should look to the example of Dieselgate. More specifically, they should seek to improve emissions enforcement by empowering non-governmental and nonprofit environmental advocacy groups such as the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT).68 Such organizations could act as private, global enforcers through a combination of funding and the creation of targeted legal causes of action. This global structure would minimize the nationalistic biases of local regulators, politicians, and citizens and eliminate the agency problem of popular indifference, ensuring that national champions like VW cannot be protected by preferential treatment.69 To ensure universal applicability, this system could be built in tandem with broader efforts to enshrine the crime of “ecocide,” or destruction of the environment, in international law.70

More proactively, governments could require carmakers to incorporate environmental and public health concerns into their decisionmaking process.71 This so-called “Environmental, Social, and Corporate Governance” (ESG) approach has been pioneered by a non-profit called B Labs. Today, the organization grades corporations around the world on their sustainability and transparency and helps them to amend their own governing documents to require consideration of the impact of their decisions on shareholders, workers, and the wider community and environment.72 In return, B Labs officially certifies these corporations as socially responsible “B Corps.” This process could remain entirely private or could be aided by the government through the creation of a new corporate form, the “benefit corporation.”73

Of course, both sets of proposals remain flawed. Like existing regulators, nonprofits are subject to the dangers of capture, particularly when dealing with donors.74 They may also struggle to overcome hostility or meet the tailored needs of individual governments and populations, especially those outside of the American sphere of influence.75 For similar reasons, both international law and ESG standards have been criticized for being cumbersome, easily manipulable, and ultimately ineffectual.76 Benefit corporations have also been attacked for implicitly excusing the socially irresponsible behavior of “regular” corporations.77

In truth, what is really needed is a universal shift in the way all institutions operate. While this change cannot occur overnight, the reforms proposed by this article are a good start. By acting together and remaining flexible in implementing such policies, governments could harness the power and efficiency gains of collective action while beginning the long and arduous process of reform. These actions would also serve to remind corporate leaders, employees, and other individuals of the seriousness of the problem, ideally inspiring them to take supplementary action. Given enough time and support, this system could herald a new era of corporate social responsibility, one where all corporations are disincentivized to cheat on emissions restrictions and those who do are held accountable.

CONCLUSION

Like the evil empire in Star Wars, emissions cheating has proven impossible to eradicate completely. In August of 2020, news broke that VW subsidiary Porsche was being investigated by American and German authorities for possible emissions cheating in petrol engines used as recently as 2017.78 As these new allegations made clear, this remains a difficult problem to fix. Employees, executives, and shareholders are all incentivized to retain the status quo, helping to prevent sorely needed reforms. At the same time, the regulators, institutions, and individuals meant to hold VW and its competitors accountable have instead become beholden to their power, leaving open only limited avenues for enforcement of emissions standards.

Today, VW’s stock is soaring, buoyed by an environmentally-friendly move into electric vehicles.79 In some sense, then, this battle is already over. However, the wider war persists at the carmaker as well as across all other emissions-producing corporations. Recently, Greenpeace accused VW of manipulating data to seem as if it is selling more electric vehicles than it actually is.80 And according to scientists in California, 2020 was one of the worst ozone years ever despite a widespread decrease in automobile usage, suggesting that NOx is not just a tailpipe problem.81

If we hope to tackle the emissions issue and save our environment and public health, we must therefore resist the temptation of half-measures or quick fixes and instead deliver real, structural change to the way we allow our institutions to engage with these problems. Instead of letting corporations and their leaders shirk responsibility, we must make it their duty to safeguard the planet and its people. At the same time, we must find an effective way to hold the inevitable rule-breakers liable for the consequences of their actions. Only then will the true lessons of Dieselgate be learned.

FURTHER READING

Beth Gardiner, Choked: Life and Breath in the Age of Air Pollution (2019).

Clifford Atiyeh, Everything You Need to Know about the VW Diesel-Emissions Scandal, Car and Driver (Dec. 4, 2019), https://www.caranddriver.com/news/a15339250/everything-you-need-to-know-about-the-vw-diesel-emissions-scandal/.

Ewan McGaughey, The Codetermination Bargains: The History of German Corporate and Labour Law, 23 Colum. J. Eur. L. 135 (2016).

Henry Hansmann & Reinier Kraakman, The End of History for Corporate Law, 89 Geo. L.J. 439 (2001).

Laura Colombo, Corporate Social Responsibility Is Not Only Ethical, But Also A Modern Business Tool, Forbes (Apr. 5, 2021), https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbeshumanresourcescouncil/2021/04/05/corporate-social-responsibility-is-not-only-ethical-but-also-a-modern-business-tool/?sh=2a304ad31bfa.

Lawrence Hurley, Supreme Court seeks U.S. government views on VW emissions case, Reuters (Apr. 26, 2021), https://www.reuters.com/business/environment/supreme-court-seeks-us-government-views-vw-emissions-case-2021-04-26/.

Suntae Kim et al., Why Companies Are Becoming B Corporations, Harv. Bus. Rev. (June 17, 2016), https://hbr.org/2016/06/why-companies-are-becoming-b-corporations.

Volkswagen Clean Air Act Civil Settlement, EPA (July 27, 2017), https://www.epa.gov/enforcement/volkswagen-clean-air-act-civil-settlement.

Volkswagen, Holocaust Encyclopedia (2018), https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/volkswagen-1.

Wolf-Georg Ringe, Company Law and Free Movement of Capital, 69 Cambridge L.J. 378 (2010).