Prologue

Reasons You Can Be Evicted in Boston

- You argued with your neighbor in the laundry room

- You set a small fire in a shared kitchen

- You called the police

- You failed to pay a parking ticket

- Your child’s girlfriend sold drugs at school

Reasons You Can Be Denied Subsidized Housing in Boston

- You make more than $22,340 a year

- Someone in your family was evicted in the last five years

- Someone in your family was evicted for drug possession in the last three years

Introduction

Since the 1980s, there has been an expansion of federal, state, and local law authorizing eviction for criminal activity. These laws have extended policing and criminal law enforcement into the home and the private rental market—where landlords select the charge, and housing courts determine guilt and dole out punishment. This growing body of punitive housing law has fostered a system of tenant screening, monitoring, and marking that extends and entrenches the harms of the criminal legal system and its discriminatory impacts on poor, Black, and disabled people. Corporate data miners and criminal record screening companies reap profit from this expanded system of surveillance, while targeted communities—predominantly poor, Black, and brown—are displaced and shut out from the rental market.

This paper seeks to understand the role of corporate power in fostering a housing system that deputizes landlords as cops and encourages eviction as punishment. Criminal act evictions are endemic to the system of mass criminalization, whereby the provision of welfare and secure housing was gradually replaced by policing and incarcerating poor people.1 While the War on Drugs shifted state resources from schools, healthcare, and housing to police and prisons,2 it imposed civil “collateral consequences” on those convicted of drug offenses—ensuring those who had arrests or convictions would be shut out of public housing and benefits near permanently. Courts and lawmakers routinely justified these policies on claims of “public safety,” “order maintenance,” and “community policing.” However, historical and sociological evidence demonstrates the system of mass criminalization has entrenched poverty, crime, and neighborhood instability, especially in inner cities, without delivering on its stated goal of public safety. Crime generates eviction, and eviction generates crime.

Who stands to benefit from a system that builds jails instead of houses?

The corporate actors that have reaped profit from the expansion of police and prisons over the last half-century. The system of mass criminalization has created numerous opportunities for profit that entrenched policing and prisons as one of the central policy responses to poverty and housing instability in the U.S. This paper will show how criminal act evictions emerged from an era in which the federal government turned toward funding police rather than welfare and corporate profits became increasingly central to law enforcement policy. By deputizing landlords as police officers, criminal act evictions have created a new “market” for corporate policing profiteers and entrenched the policy of policing depravity.

Part I describes the use of eviction as a law enforcement strategy. Part II identifies the overlapping policy justifications for eviction and policing, rooted in racialized myths of Black community disorder. Part III contextualizes the emergence of criminal act evictions in the system of mass criminalization and the outgrowth of police profiteering. Part IV concludes by advocating policies that prioritize the provision of stable housing as a pillar of decarceration and public safety.

Part 1: Landlords as Law Enforcers

Beginning during the Reagan War on Drugs, federal law imposed collateral sanctions that purported to deter crime by denying housing to the accused and convicted. The Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988 authorized eviction from public or federally subsidized housing for criminal activity.3 It also encouraged local police and public housing authorities to fight drug crime in public housing projects by allocating federal block grants for precisely this purpose.4 Drug enforcement accelerated in public and low-income housing, while the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and Congress expanded the net of housing penalties for crime, from the application stage (permitting housing denials based on criminal history) to termination (broadly articulating the crimes that were grounds for eviction).

This policy, later dubbed the “one-strike” rule, created an eviction dragnet. Tenants faced eviction not only for their own alleged criminal behavior but that of their household members and guests—even if the tenant was unaware of the crime.5 At Clinton’s urging, Congress expanded the net in 1996 to include criminal activity that occurred off the leased property.6 In the 2002 decision HUD v. Rucker, the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously upheld the law as a reasonable response to the “reign of terror” wrought by “drug criminals” in public housing.7 Rucker legitimated the conflation of “crime” and “drug crime,” tenants and their communities—and deepened the cultural notion that public housing and crime run together. Perhaps most harmfully, the federal one-strike policy also legitimated eviction as a form of criminal punishment and deputized property managers as law enforcers.

Federal housing regulation provides a public housing authority may evict a tenant if the tenant has engaged in criminal activity “regardless of whether the [tenant] has been arrested or convicted” and “without satisfying the standard of proof used for a criminal conviction.”8 This means landlords and public housing authorities define what constitutes “crime”—and receive federal funding incentives to set the bar low.

Beginning in the 1990s, local legislatures replicated the federal regime in the form of “crime-free housing” ordinances (CHOs)—which extended criminal act evictions into the private market, and in many cases, mandated evictions for illegal activity.9 Nearly two-thousand cities and towns have enacted a CHO.10 The majority of low-income tenants live in privately-owned housing and receive no rental assistance; CHOs thus dramatically extend the reach of the punitive one-strike policy.11

Scholars and activists have decried the rise of criminal act evictions for their impact on survivors of domestic violence and people with disabilities—people who might wish to rely on the police for safety but find themselves paying the price of eviction.12 People who are listed on sex offense registries are also uniquely impacted. This paper focuses on the role of corporate power in expanding the net of criminalization into the housing market and the distinct harms of extending the function of law enforcement and criminal adjudication into the hands of landlords, public housing authorities, and housing courts.13

Housing courts claim to maintain order and safety in residential communities but in fact deepen the instability that gets labeled as “disorder” and create new pathways for arrest and incarceration. In this sense, federal, state, and local housing law have come to operate as an extension of criminal legal system.

Here’s how this plays out in practice:

Eviction proceedings stacked against tenants

Mere allegations of criminal activity—often layered with racial stereotypes and disability stigma—can be enough to evict a tenant from their home. Eviction cases are heard in civil housing court, where tenants lack the constitutional protections of criminal defendants. Tenants facing eviction have no right to a state-appointed lawyer. As a result, more than 90% of tenants do not have a lawyer, and more than 90% of landlords do.14 Landlords need only prove their allegations by a preponderance of the evidence—a lower legal standard than the criminal “beyond a reasonable doubt.” Facing this power imbalance and low standard of proof, tenants accused of criminal activity can be evicted after a swift bench trial or simply default for failing to appear.15 In this way, the housing court operates as a faster, more efficient venue for criminal law enforcement.

Family separation

The breadth of criminal act evictions makes them uniquely punitive. Under federal and local housing law, tenants can be evicted for the alleged acts of their family members and guests—even if they occurred off the premises. These cases are often settled with the imposition of a permanent ban on the family member alleged to have committed the crime. In addition, families can face eviction or lose their rental subsidy for taking in a friend or family member recently released from incarceration. These policies have disparate impacts on Black and Latinx as well as disabled tenants, whose conduct is likely to be labeled “disorderly.”16 Criminal act evictions expand the scope of punishment beyond an arrest or criminal sentence: families, friends, and communities are displaced and struggle to find housing with an eviction record.

Screening, monitoring, and extension of policing

Tenants applying for housing face two tests: eviction history and criminal record screening. Federal regulation provides a tenant’s public housing application may be rejected if anyone in the tenant’s family has been evicted in the past five years.17 Though in most cases, federal regulations permit, rather than require, denial of public housing based on criminal records, public housing agencies widely abuse their discretion and deny those with criminal records outright—even those with mere arrest records.18 When it comes time for annual recertification of a rental subsidy, tenants are screened again and may be evicted for criminal activity that occurred during the course of the tenancy. Criminal act evictions thus facilitate dragnet policing and monitoring at all stages of tenancy.

Local “crime-free housing ordinances” (CHOs) exacerbate the problem of screening and monitoring by strengthening ties between private landlords and police departments. Many CHOs make landlords liable for failure to evict a tenant accused of crime.19 Landlords are encouraged to keep a close watch over tenants and in some cases are required to submit lease violations to the police department. Police and prosecutors rely on this information to pursue low-level crimes of poverty, like loitering and disorderly conduct, as well as charges of criminal fraud for violating subsidized housing rules.20 These practices underscore the law enforcement function of criminal act evictions: by collecting evidence of criminal activity and evicting tenant-suspects, landlords investigate crime and expose their tenants to policing and prosecution.

The growing overlap between policing and housing law creates opportunities for corporations to extract profit by labeling tenants “safe” or “dangerous.” 90% of landlords use background checks to screen prospective tenants.21 Landlords purchase automated tenant screening services, which aggregate eviction records, criminal records, and credit scores, and recommend that landlords accept or reject the tenant based on opaque algorithms.22 Background check companies encourage landlords to make decisions based on information encoded with race and class bias—eviction and criminal records.23 In this sense, these companies encourage and profit from housing discrimination: the mark of criminality is a product to be packaged and sold.

Part 2: The Illusion of Order

Criminal Act Evictions Generate a Cycle of Eviction, Homelessness, and Incarceration

Police, courts, and lawmakers defend criminal act evictions on grounds of crime prevention and public safety. In this frame, the things that make criminal act evictions suspect—the power of private landlords to obtain tenant information and enforce criminal law—are efficient tools of snuffing out crime before it occurs. Criminal act evictions are an iteration of “broken windows” policing—a disproven, but widely invoked, theory that maintaining community order by heavily policing low-level offenses will prevent violent crime.24 In much the same way as “order maintenance” policing, criminal act evictions create a fleeting illusion of order. Eviction forces the “problem” tenant from the property on a premise of restoring safety, order, and equilibrium to the community.

Does “order” really follow eviction?

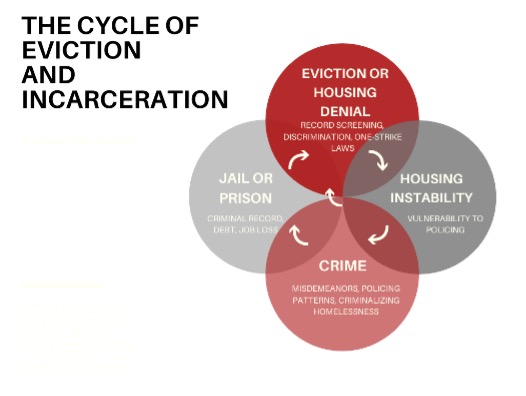

Eviction causes long-term housing instability, homelessness, and severe mental and physical health consequences.25 Shut out from the housing market, people accused and convicted of crime frequently experience homelessness. Conditions of homelessness and housing instability dramatically increase the risk of criminal legal system contact and reincarceration, which in turn can expose family and friends to eviction.26 Criminal act evictions have the absurd effect of replicating and entrenching the problem they claim to solve. The result is a brutal cycle of eviction and incarceration.

Claims of “urban disorder” have long been invoked to justify expanded law enforcement presence in low-income, predominantly BIPOC communities—when the source of community instability is in fact systemic denial of jobs and housing, eviction, and residential segregation.27 Historically, policing has played a central role in concentrating economic disadvantage by enforcing the boundaries between “Black” and “white” neighborhoods, subjecting Black communities to surveillance and violence, and justifying racially disparate enforcement on claims of order maintenance.28 Criminal act evictions codified the deep relationship between housing instability and policing—legitimating the use of landlords and housing law to criminalize and control low-income communities.

Housing courts demand that we look away from the systemic roots of violence and instability in our neighborhoods. Eviction becomes an individual dispute between a landlord and tenant, divorced from context. In this frame, the tenant is the problem—rather than the systems of policing, drug policy, and denial of economic opportunity—and eviction is a sound solution. Eviction proceedings operate from a baseline assumption that displacement is a rational response to difficulty, disagreement, or a mere desire on the part of the landlord to do something else with their property. In Rucker—the Supreme Court decision that upheld criminal act evictions even where the tenant was unaware of the criminal acts of a household member or guest—the Court used the displacement baseline to justify the result. The Court reasoned, a “no-fault” eviction is a “common incident of tenant responsibility under normal landlord-tenant law and practice.”29 Evicting a tenant for criminal acts in which they had no part and no knowledge is an efficient way to enforce the law and “maximiz[e] deterrence.”30 The Court here endorsed the presumptions—pervasive in housing law—that landlords are rational actors, and tenants must bear the risks associated with the tenancy. The Court did not appear to consider the consequences of such a rule.

Background check companies capitalize on the narrative of the rational landlord/problem tenant by applying numerical assessments, akin to credit scores, to tenant “risk.”31 CoreLogic, a multi-billion-dollar data company, has trademarked its “SafeRent Score” that claims to predict accurately whether the tenant will pay rent on time and comply with the lease.32 As researchers with the Shriver Center for Poverty Law observed, this score “simplifies and hides a wide variety of biased indicators” behind a claim of safety.33 CoreLogic legitimates the landlord’s choice to screen out “dangerous” tenants through its claim to precision, data, and “science.”34 Meanwhile, there is no assurance that CoreLogic’s databases reflect current and accurate criminal and eviction records.35

Part 3: Who Benefits from Criminal Act Evictions?

The War on Crime, the Collapse of Welfare, and the Rise of For-Profit Policing

Eviction is a counterproductive response to crime, disorder, and neighborhood disputes: by generating instability and deprivation, housing law creates the problems it purports to address. So why have federal, state, and local governments chosen to punish crime with eviction, housing denials, and heightened surveillance?

This Part probes the dominant ideologies and profit motivations that transformed housing law into a system of law enforcement. Section III.A describes the federal centralization of law enforcement beginning in the 1960s, which incentivized local governments to invest heavily in policing, rather than welfare, and laid the infrastructure for mass criminalization. Section III.B examines how the growth of policing created opportunities for profit extraction that entrenched punitive approaches to poverty and housing instability. As profit maximization becomes increasingly central to law enforcement, it is clear policing and punishment, let alone eviction, have little to do with crime and public safety.

Federal Control of Welfare and Police: The Punitive Turn

Criminal act evictions arose out of the Reagan War on Drugs, an era in which law enforcement became primarily driven by profit—for local police departments and for the corporations that comprise the prison industrial complex. These extractive policies would not have been possible without a federal system that encouraged local governments to invest heavily in policing and to merge police and social service agencies.

Historian Elizabeth Hinton argues the Johnson administration’s dual Wars on Poverty and Crime laid the foundation for a “merging” of policing and welfare that fundamentally changed law enforcement in the U.S.36 The Law Enforcement Assistance Act of 1965 funded “experimental” local law enforcement programs that ranged from subsidizing military equipment for local police departments at 90% cost to pilot programs placing police in schools.37 The Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968 allocated an unprecedented $300 million to federal investment in state and local police agencies—the first major instance of block grant funding, which would become the model for federal police reform that persists to this day.38

Hinton argues Johnson’s welfare policy had been premised on the racist belief that “black community pathology caused poverty and crime”—an idea that Harvard sociologist David Patrick Moynihan developed and promoted.39 The pivot from providing welfare to deploying police to poor communities in this sense was unsurprising. But the creation of a federal law enforcement bureaucracy that incentivized state and local investment in policing brought about a profound shift in American policing that allowed the prison industrial complex and the policies of mass criminalization to blossom and grow.

“[The Johnson] Crime Commission supported a punitive transformation of urban social programs, based largely on the principle that saturating a targeted area with surveillance equipment and police officers performing both social welfare and crime control functions would effectively restore order. The process of implementing this strategy from the late 1960s onward eventually criminalized generations of low-income black Americans.”40

– Elizabeth Hinton

These Nixon, Reagan, and Clinton administrations expanded on the War on Crime to victimize Black communities through drug enforcement, massive divestment from welfare programs, and increasingly steep criminal penalties. In 1970, the Nixon administration amended federal forfeiture law to encourage local police to seize assets “associated with” drug crime. In 1986, Congress dissolved the Johnson-era Law Enforcement Assistance Administration, replacing it with Edward Byrne Program, which conditioned federal block grants on drug enforcement.41

Scholars have demonstrated how federal laws expanding asset forfeiture and block grants heavily influenced the choices of local police and prosecutors to pursue cases that would maximize profit for the department.42 Anything police and prosecutors did to “solve” crime was “largely the unplanned by-product of this economic incentive structure.”43 We know from the work of Michelle Alexander, Bruce Western, and others that drug enforcement targeted poor communities of color, producing the effect of “warehousing” people who would otherwise struggle to find stable employment and housing in conditions of economic deprivation.44 The policies of mass criminalization produced a dramatic increase in state and local police spending that persisted even as crime rates started to decline in the early 1990s.45

Who benefits from the punitive approach to poverty?

The New Policing Profiteers

The punitive turn in federal poverty policy has generated countless opportunities for profit extraction. Corporate law enforcement profiteers have entrenched, influenced, and profited from the series of policy choices that meet poverty with policing and surveillance.

The corporate law enforcement lobby, led by private prison companies, played a pivotal role in advancing the mass criminalization policies described above. This legislative effort and its devastating impact have been well-documented elsewhere.46 Perhaps less discussed is the recent expansion of policing profiteers,47 who stand to profit the most from the criminalization of low-income housing.

Corporate Software Developers: Predictive Policing, Surveillance Systems, and Racist Algorithms

The War on Crime effort to fund local police “innovation” has a dark legacy. Massive technology companies, including IBM, Microsoft, and Amazon, generate increasingly advanced—but demonstrably racist48— facial-recognition and biometric services to compete for police contracts.49 These tech companies—the new police profiteers—play an outsized role in shaping police policy under the guise of reform, rigor, and precision. Under claims of expertise in “regulating” the growing industry, Amazon and Microsoft have drafted policies that protect the market for their facial recognition products.50

Facial-recognition software is deployed across communities through panopticon-like surveillance systems that cover increasingly large areas through the use of GPS technology. Microsoft recently came under fire for its multi-million-dollar partnership with the NYPD to implement and maintain the “Domain Awareness System” (DAS), which boasts “the largest networks of cameras, license plate readers, and radiological sensors in the world.”51 Beyond DAS, the NYPD uses gunshot “detectors” and predictive “crime-pattern-recognition” software to patrol communities in a city where Black residents are killed by the NYPD more than fives times as often as white residents.52 In Baltimore, a majority-Black city, police piloted a pervasive aerial surveillance system, originally designed for the U.S. military in Iraq and Afghanistan, capable of photographing 32 square miles per second.53 Bloomberg reported this system was used to identify Black Lives Matter protesters after Freddie Gray’s murderer was acquitted in 2016.54 In 2020 alone, Baltimore spent $3.7 million on the program—underwritten by a “Texas-based billionaire philanthropist” John Arnold.55

Not only do biometric surveillance systems misidentify women and people of color—subjecting them to wrongful arrest and detention—they are disproportionately installed in poor communities of color, reinforcing the spatial policing practices that criminalize poverty.56 With the aid of tech profiteers, police no longer need to patrol public housing; they are ever-present through wide-angle cameras and drones. As “progressive” cities like New York, Los Angeles, and Baltimore invest heavily in surveillance infrastructure, it becomes harder to dial back the punitive approach to poverty. As activist Malkia Devich-Cyril wrote for the Atlantic, “White supremacy defines how society is structured and how new technologies are used, and it moves at the pace of capital…In an era when policing and private interests have become extraordinarily powerful—with those interests also intertwined with infrastructure—short-term moratoriums, piecemeal reforms, and technical improvements on the software won’t defend Black lives or protect human rights.”57

Corporate Data Brokers: Criminal and Eviction Record Screening

While racist surveillance systems increase arrests and monitoring of poor communities, the data services industry commodifies the arrest, conviction, and eviction records that follow. The criminal background check industry was estimated at $4.06 billion in 2018 and is expected to reach $7.64 billion by 2026.58 32% of industry revenue comes from prospective tenant reports.59 Background screeners obtain records from private data companies, which purchase data from law enforcement agencies or scrape public websites for criminal record information.60 Screeners then market their services to landlords and employers, advertising the scope, speed, and accuracy of their record reports—but these records are several degrees of separation from the police department that created them and are often rife with error.61

Background record companies are the quintessential parasitic law enforcement profiteers—the more communities invest in the practice and legitimacy of policing, the more business they receive. Background companies facilitate the extension of policing into the housing and job markets and literally profit from stigma and discrimination based on arrest and conviction histories. The more we rely on policing as a valid indicator of safety, the greater their profit.

Impact

Data and surveillance technology are just two examples of corporations investing in mass criminalization. Other prominent police profiteers produce weapons, equipment, and telecommunications systems.62 The power and profit generated by law enforcement profiteers are perhaps ironically concealed by the profound reach of policing—with so many discrete opportunities to extract profit, police profiteers need not unite their interests in a single corporation, nor need they share identical lobbying goals. However, corporations’ parasitic relationship to policing serves to entrench law enforcement infrastructure and increasingly drive police reforms to serve profit motivations. With so much to gain from law enforcement, corporations perpetually influence police policy in the direction of expansion and growth with no regard to public safety or the long-term well-being of the communities targeted by police.

By endorsing shareholder primacy and the single interest in profit, corporate law provides no pathway to hold police profiteers accountable nor any kind of duty to the people impacted by their extractive technologies. Federal crime policy, starting in the Johnson administration, laid the infrastructure for mass criminalization and chose policing as the dominant anti-poverty strategy. Corporations ensured policing would remain dominant by investing heavily in the systems that punish, rather than alleviate, poverty.

Conclusion: The Crisis of Police Legitimacy and the Urgency of Abolition

Policing is in a crisis of legitimacy.63 As more and more people hear the cries of Black activists, the survivors of generations of police profiling, abuse, and killings, it is clear that policing has never promoted safety. As federal policy has increasingly chosen policing as a poverty intervention, housing and welfare law, too, become estranged from prosocial goals.

Decarceral policy requires that we empty prisons and defund police in their traditional forms; it also requires that we build the world that prioritizes repair, rather than punishment, and we remove carceral strategies from all corners of governance.

Criminal act evictions reveal the danger of a housing system that adopts policing strategies and technologies to extract profit from marginalized communities. Decisions about who deserves shelter should not be rooted in a narrow profit motive that benefits only a few. We need to respond to poverty with housing, not eviction and jail.