INTRODUCTION

“Nobody stopped it. Nobody in Florida with the power to do so stopped the state from forcing a 9-year-old boy named Michael, who was born with a brain stem but not a complete brain, from taking an alternative version of the standardized Florida Comprehensive Assessment Test. He is blind and he can’t talk, nor can he understand basic information, but, yes, Michael had to “take” the test.” 1

-Valerie Strauss, Reporter for The Washington Post

In today’s day and age, standardized testing and education go together like peanut butter and jelly. It is quite difficult to imagine one existing without the other. While there are hundreds of standardized tests purporting to measure intelligence levels in a wide variety of subjects across our nation’s schools, this piece focuses on one in particular: the Law School Admissions Test (LSAT). As a first generation daughter of Latinx immigrants law student who recently went through the law school admissions process, I feel most prepared to address the systemic injustices currently surrounding me and my peers as a result of higher education’s hand in corporate law and corporate theory by proxy of standardized testing companies like the Law School Admissions Council (LSAC).

Corporate law and theory sustain the systemic injustices found in higher education because corporate law enables the formation and upkeep of standardized testing industrial complexes including the companies that produce standardized exams, the higher education institutions that require them for admissions, and the news companies that rank higher education institutions. Corporate law and theory provides the legal admissions business a shared, single interest or purpose with which to influence and (deeply) capture laws, institutions of influence, expectations, norms, that together produce and “legitimate” unmerited hierarchies in the form of standardized test scores and admission to prestigious colleges/universities, and eventual wealth inequalities later on in life as a result of test scores obtained when one is 16-17 years old.

PROBLEM DESCRIPTION

“Education, then, beyond all other divides of human origin, is a great equalizer of conditions of men—the balance wheel of the social machinery.”

Horace Mann, 1848, as cited in Education and Social Inequity2

In their article, Educational Equity in America: Is Education the Great Equalizer?, Roslin Growe and Paula Montgomery from the University of Louisiana at Lafayette explain that “From its inception, American public education has had as one of its tenets the notion of being that remedy by which inequality of opportunity and poverty can be reduced, thereby becoming the great equalizer.”3

Law schools promote “equality” in law school admissions, regardless of an applicant’s undergraduate institution or area of study, through the use of the LSAT.4 In 1945, the admissions director at Columbia Law School wrote a letter to the College Entrance Examination Board “suggesting the creation of a ‘law capacity test’ to use in admissions decisions,”5 with the goal being to “promote fairness in law school admission by opening the door to all qualified candidates regardless of their undergraduate institution or area of study.”6 The College Board responded favorably and invited representatives from Columbia, Harvard, and Yale to join in the planning and financing of the proposed legal studies admission exam.7 All schools agreed that the test must be designed “specifically for legal education and focused on core reading and reasoning skills.”8 The LSAT was then born and first administered on February 28, 1948.9 About twenty years later in 1968, the Law School Admission Test Council (now known as LSAC) is incorporated under New York education law.10 Law schools now exist as independent corporations and as unified all-powerful entities that all hold membership under LSAC.

The problem with the close association between standardized testing and education is seen through the following collective narrative: our country’s education system provides a story that those who are better off are better off because they worked harder, thus, our education system as a whole is generally seen as a gateway for equality.11 The history behind this narrative goes back to when the Puritan settlers settlers established America’s first public schools in 1635.12 Massachusetts led the way by appointing the first ever education secretary, Horace Mann. The story goes: everyone has a shot at it, it’s about what YOU do with it. This narrative is false.

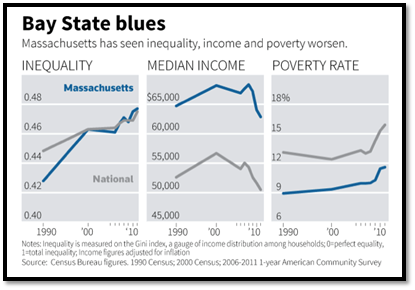

“Yet over the past 20 years, America’s best-educated state [Massachusetts] also has experienced the country’s second-biggest increase in income inequality…As the gap between rich and poor widens in the world’s richest nation, America’s best-educated state is among those leading the way.”

– Reuters analysis of U.S. Census data13

Figure 1: Wealth inequality in Massachusetts

“Between 1989 and 2011, the average income of the state’s top fifth of households jumped 17 percent. The middle fifth’s income dropped 2 percent, and the bottom fifth’s fell 9 percent. Massachusetts now has one of the widest chasms between rich and poor in America: It is the seventh-most unequal of the 50 states, according to a Reuters ranking of income inequality. Two decades ago, it placed 23rd.”14

Standardized exams are not merit based. Standardized exams serve as markers of wealth. We can assume that the LSAT measures wealth since standardized tests in general measure wealth. According to the Washington Post, in 2014 “students from families earning more than $200,000 a year average a combined [SAT] score of 1,714, while students from families earning under $20,000 a year average a combined [SAT] score of 1,326.”15 Another recent report from the Georgetown Center on Education and the Workforce, “Born to Win, Schooled to Lose,” explains that being born wealthy is actually a better indicator of adult success in the U.S. than academic performance. “To succeed in America, it’s better to be born rich than smart.”16

The wealth -performance connection will disproportionaly disadvantage people of color. As of 2016, the net worth of a typical white family is nearly ten times greater than that of a Black family.17 It then comes as no surprise that in the 2008-2009 school year, white LSAT-takers scored on average ten points higher than Black LSAT-takers and six points higher than Latino/a LSAT-takers.18

“The theory and design of college admissions tests continue to falsely assume that mathematical and verbal reasoning are universal. Both tests not only assume that processes of human reasoning are the same for everyone, but that human reason behaviorally manifests the same across social and cultural context and history.”19

Ezekiel J. Dixon-Román

Associate Professor in the School of Social Policy & Practice at the University of Pennsylvania

CURRENT DOMINANT NARRATIVES

For 71 years, LSAC has known its exam and admissions practices leave out under-resourced stakeholders. LSAC has been promoting its diversity initiatives since 1950 when it formed the “Background Factors Committee” to address the underrepresentation of disadvantaged and diverse students.20 The call for equity in law school admissions is not new. LSAC has been aware of the harm it has been causing on the law school admissions process for underrepresented folks since its inception, they had the data. Underrepresented folks in law school admissions include but are not limited to racial minorities, first generation and low income students.

Proposed solutions LSAC has come up with include offering free “Official LSAT Prep” that includes 3 practice exams, access to practice on the exam interface, and instant scoring feedback.21 LSAC’s solution does not address the fact that its exam is measuring wealth. Wealth is not erased by providing some access to what the exam will entail. LSAC’s practice of providing some exposure to the exam is a half-hearted attempt at bandaging the systemic issues involved in why under-represented folk score lower by further legitimizing the LSAT.

Additionally, LSAC has invested in a “Minority Fund” that “provide[s] support to programs that enhance legal education opportunities for students from diverse backgrounds” and in providing LSAT test fee waivers for students who are able to show demonstrated financial need.22 These proposed solutions by LSAC also fail because financial access to their exam and what the legal profession entails once again, does not equal erasure of what their exam does—measure wealth. Law School recruitment efforts often rationalize that the LSAT is only ONE of a plethora of factors considered on one’s law school application. Affirmative action has undoubtedly opened the door for minorities to be admitted into elite law schools. However, the advent of affirmative action did not erase the fact that the LSAT continues to measure wealth instead of legal reasoning skills. In using affirmative action as a factor for admission, law schools continue to legitimize the LSAT’s purpose by still requiring it and comparing students of the same race to each other.

Dana Goldstein, a journalist and author of The Teacher Wars: A History of America’s Most Embattled Profession explains that “This is the era where we begin to see teachers’ unions and parents say: ‘There’s too much testing; bad tests; and they’re too high-stakes.’” In response, advocates of [standardized] tests say they provide important data to hold schools accountable for educating all students and closing the achievement gap.23 Providing data on measuring a student’s wealth will never help close the achievement gap if no effective mechanisms are put in place to act as a result of that data. Standardized test companies like LSAC, in their corporate, profit oriented mindset, will always do everything they can to sell their product (the exam). The continuous data collection on behalf of standardized testing companies is overkill at this point: we get it—there are wealth disparities across races and socio-economic classes… what is another test measuring that going to do about it? When we test students as a form of holding a school accountable in reaching equitable district mandated goals, the testing efforts prove to be futile in remedying systematic inequitable educational outcomes. The testing of students as a form of school accountability in reaching calls for equity proves to be futile in remedying systemic inequitable educational outcomes.

ANALYSIS OF THE ROLE OF CORPORATE POWER

“If only U.S. schools, teachers, and students were treated like iPhones. Take the first-generation iPhone. To enable users to swipe, pinch, and scroll with their fingers, “making for a more immersive experience,” Apple, in the early 2000s, spent approximately 150 million in development costs….From the perspective of what the overall economy needs, or, to put it more bluntly, what corporate heads and their political allies decide it needs, similar investments in schools and students are not regarded as comparable, because, as educational psychologist Milton Schwebel concluded in his analysis of the three tier US educational system, the US economy “has no need for a well-educated populace. The hard fact is that the economy operates perfectly well” with the top tier schools providing well skilled workers and the middle tier providing workers for the middle tier of jobs (in offices, retail stores, hospitals…), and the third tier fills the ranks of unskilled service workers and the unemployed. Hence, funding and resources are proportionally distributed across these tiers. Were there really a crisis of public schools not meeting business needs for skilled workers, surely corporations would look up “what works” among schools, families, students, and communities that do produce the needed skilled workers and would strive to duplicate throughout the nation those quality elements for success.”

Gerard Coles24

Miseducating for the Global Economy: How Corporate Power Damages Education and Subverts Students’ Futures, 2018

Corporations (U.S. News) and their not-for-profit dependent counterparts (LSAC, Law Schools) wish to keep wealth in a tight, contained circle–perpetuating these circles down generations requires beginning to “sort” who will have access to wealth as early as high school. What the corporations are sorting for is wealth under code for “intelligence/capacity”. The sorting tool they use are standardized tests. This sorting tool legitimizes their goal of keeping wealth for the wealthy by portraying it as an “equitable” way for everyone to try their shot and work their hardest for the best scores.

LSAC’s role in catering to a for-profit industry

LSAC labels itself as a not-for-profit organization.25 While LSAC’s non-profit status may lead many to believe its intetions are noble and not incentivized by profit alone, the fact is that LSAC’s very existence depends on its success in suriving within a for-profit world. Thus, hiding behind the guise of a nonprofit, LSAC operates with profit driven incentives typical of U.S. for-profit corpoations. For example, LSAC caters its product to law schools which are also non-profits. Law schools then use LSAT scores to boost their rankings on U.S. News reports. LSAT score medians for each incoming first year law school class are heavy factors in a law schools U.S. News ranking.26 The higher the median LSAT score of a law schools incoming class, the higher the ranking. U.S. News is a for-profit corporation that promises to be a “trusted authority providing empowerment and guidance that improves the quality of life for consumers and communities at the local, national, and global levels, U.S. News leads to better life decisions.”27 A law schools ranking on the U.S. News best law schools list is meaningful to law schools. The higher the ranking, the more alumni will donate, the more applications you will receive in an application cycle, and the more prestige the school garners.

U.S. News is a faulty metric for accountability

There is an issue of accountability when U.S. News is responsible for determining which law schools are “the best” by using a set of criteria that continues to reward the affluent and exacerbate wealth inequality. U.S. News heavily takes into account the LSAT, a test measuring wealth, into its law school rankings. This incentivizes law schools to “buy” test scores using “merit” scholarships to attract the highest test scores to their universities. Why do law schools offer merit scholarships? The short answer is to “build the best class that money can buy, and with it, prestige.”28 U.S. News itself acknowledges this incentive they create:

“Law schools have an incentive to use financial aid to entice applicants with highly competitive profiles to accept admission, because the average GPA and LSAT scores of a law school’s entering class are among the factors in law school rankings and reputation. Thus, law schools channel merit aid to applicants whose acceptance would raise the bar for the entering class. In other words, raising your LSAT score may substantially trim your tuition.”29

In our current law school admissions landscape, accountability to principles of equity for all applicants, regardless of wealth, is no where to be found. Let’s take an inventory here: we have an exam–the LSAT– that measures wealth. We also have a “not-for-profit” organization–LSAC–that continues to sell its test to law school applicants as a measure of law school capacity when in reality the test is only measuring wealth, not intelligence. These LSAT scores of wealth are then fed to law schools who are then graded by U.S. News for how many of the “highest scores,” code for “highest wealth,” they were able to accumulate at their school. Law schools are rewarded by U.S. News for the the greater number of “highest” wealth scores they can accumulate by being labeled with a higher ranking. Where is the accountability here?

LSAC’s interests vs. LSAC’s mission statement

The LSAC not-for-profit model operating in a for-profit ecosystem with U.S. News, does not square with our society’s narrative of education working as a great equalizer. LSAC’s mission statement claims to promote equitable education ideals we are familiar and comfortable with. The LSAC mission statement reads as follows:

“The Law School Admission Council is a not-for-profit organization committed to promoting quality, access, and equity in law and education worldwide by supporting individuals’ enrollment journeys and providing preeminent assessment, data, and technology services.”30

While LSAC’s mission statement talks the talk of equity, LSAC’s statements are nothing but hollow sentiment. There is a gap between what LSAC claims it does and what the corporation is actually doing. Maximization of profits as a corporate interest valuable to law schools being held “accountable” to U.S. News prevents LSAC from equitably administering its exam. Higher education institutions, and corporations that hire from those institutions needed a way to sort out who was worthy of admission/employment—LSAC enters the chat. LSAC came up with an exam (a product) that satisfied the institution’s need of an efficient and “legitimate” way to measure intelligence. LSAC has every interest in ensuring its product survives—without it, LSAC will be no more.

Corporate gaps between what they are outwardly projecting to our populace and what they are actively doing do not end at their mission statements. In Cole’s chapter on Corporate Tears but No Taxes, Cole explains that “parallel with corporate America’s complaints about the failures of US schools to meet business needs are the numerous corporate schemes that underfund US education and thereby impair school’s ability to meet these purported needs. An analysis by Citizens for Tax Justice (CTJ) of 2008-10 state taxes found that the 265 largest companies, after raking in a “combined $1.33 trillion in profits,” paid an average of three percent in state taxes, less than half of the average state tax rate.”31

LSAC’s Capture

Shallow Capture

The American Bar Association (ABA) accredits law schools, the accredited law schools in turn make up the 203 members of the Law School Admissions Council (LSAC). LSAC does not have an official government mandated “regulator” of sorts. It is fair to assume that LSAC is self-regulating through its member law schools, and the ABA who accredits them. Shallow capture, the idea that capture is a problem with respect to administrative agencies, does not entirely apply here because no official government agencies are involved in regulation of LSAC’s exam, the LSAT.32 However, if we view LSAC as the corporation and law schools as the “regulators,” it becomes evident that law schools (the members of LSAC) are regulating LSAC to best serve themselves. The very “regulators” of the industry (LSAC) are the members of the industry.

The consequences of this “self-regulation” have been catastrophic to goals of education serving as the “great equalizer”. An example can be drawn from the aforementioned discussion on U.S. News being a faulty measure of law schools/LSAC’s accountability. Wealth inequality continues to widen as a result of the lack of a proper mechanism of accountability to protect the more vulnerable, less wealthy stakeholders who are sold a lie from LSAC’s empty equity store.

Deep Capture

LSAC’s legitimacy relies on the legitimacy of standardized tests (and therefore has to deeply capture public perceptions of standardized tests). LSAC’s very survival depends on the entire legal field and prospective law school applicants legitimizing its exam.33 The LSAT administered by LSAC is “the only standardized test accepted by all ABA-accredited law schools in the United States.”34 The mission statement page on the LSAC website also explains that “the test helps law schools make sound admission decisions by assessing critical reading, analytical reasoning, logical reasoning, and persuasive writing skills — key skills needed for success in law school.”35

Deep capture is found in the culturally reinforced stories about markets being good.36 One of these culturally reinforced stories involves the idea that we have consumer sovereignty. LSAC plays into this notion of consumer sovereignty by allowing law school applicants to choose which law schools they want to apply to, study as much as they want for the LSAT, and by providing a variety of resources for applicants (consumers) to choose to use to prepare for the exam. In turn, you are led to believe that your ultimate law school outcomes are a direct result of all of these choices that you made (ex. If you do well, you chose well; if you do badly, you chose badly) when in reality your ultimate outcomes are much more closely related to your wealth and resources. Corporations have convinced society that everyone can take the exams and everyone can study, surely one is responsible for their own test scores. This analysis references individuals as “sticks” and “balls”.37 Sticks are folks who are solely responsible for their own life consequences. Balls are people who blame a variety of outside factors in having pushed the individual to behave the way they did. LSAC, Law Schools, and U.S. News thrives off of having folks believe they are sticks. These entities have successfully made everyone believe that standardized tests are a stick approach–no balls included.

This idea of choice when it comes to law school admissions is an illusion. Do law school applicants really have the power of choice in deciding where to apply and how well they will do on the LSAT? The answer depends on how big your wallet is—hence the illusion. If you are financially privileged, you have choice—if you are low income, you have significantly less choice. Let’s break down the costs associated with law school applications.38

LSAC has taken over the entire law school admissions process. For example, you must make an LSAC account to even access law school applications AND to register to take the LSAT. LSAT registration will run $190. LSAT prep can run anywhere from a couple hundred dollars to a couple thousand the higher the price, the more quality the tutoring. Once you take the LSAT, LSAC then requires you to pay $195 for access to their “Credential Assembly Service” (CAS). CAS is LSAC’s application feature where you can upload all of your application materials in one place and send them to multiple schools. Once all of your application materials are in one place by using CAS, LSAC produces a CAS Report which will run you $45 to send to each individual school you choose to apply to. In addition to the $45 CAS report per school you choose to apply to you are also responsible for paying an about $80 application fee per school. The only law school applicants who are free to choose in this admissions process are those who are able front the expensive costs associated with applying.

CONCLUSION

The LSAT is just the tip of the “wealth” iceberg

While this paper hopes to have clearly delineated the fact that the LSAT is actually a marker of wealth and not of law school capacity—I would be remiss to not mention what an admissions world without the LSAT would look like. The troubling truth is that a law school admissions world without the LSAT still contains heavy signals of wealth markers that will continue to exacerbate wealth inequalities. The entire law school application process is sprinkled with dozens of wealth markers beyond that of the LSAT such as undergraduate institution ranking, summer internship prestige, legacy status, sports participation, etc.

Getting rid of the LSAT will not solve the larger systemic issues in education. We have a much larger systemic issue on our hands: Standardized testing or not, the reality is that our society’s educational outcomes are almost entirely wealth determined. Standardized tests such as the LSAT are only one example of hundreds that can be drawn from in proving this point.

I challenge the reader to think about an admissions world that incorporates metrics that can fairly lift people out of poverty and provide actual opportunities for social mobility sans markers of wealth that universities are rewarded for admitting.

FURTHER READING

•Robbins, M. E. (2017). “Race and Higher Education: Is the LSAT systemic of racial differences in education attainment?,” SUMMER PROGRAM FOR UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH (SPUR). Available at http://repository.upenn.edu/spur/18.

•Haddon, Phoebe A. and Post, Deborah W. (2006) “Misuse and Abuse of the LSAT: Making the Case for Alternative Evaluative Efforts and a Redefinition of Merit,” ST. JOHN’S LAW REVIEW: Vol. 80 : No. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/lawreview/vol80/iss1/3.

•Ezequiel J. Dixon-Roman & John J Mcardle, Report on Race, Poverty and SAT Scores: Modeling the Influences of Family Income on Black and White High School Students’ SAT Performance, TEACHERS COLLEGE RECORD (May, 1, 2021, 8:54 AM), https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280232788_Race_Poverty_and_SAT_Scores_Modeling_the_Influences_of_Family_Income_on_Black_and_White_High_School_Students’_SAT_Performance.