OPENING

I am not quite sure when it first became clear to me that charity, rather than accountability, was the pro-forma method of erasing one’s corporate wrong-doings from public conversation, but I remain struck by this every time I see it displayed in its most boastful fashion. One such instance occurred during one of my earliest walks through Cambridge. Wandering around with no real destination in mind, I happened to go past Harvard’s Arthur M. Sackler building. The name jolted me out of my meandering in the beautiful New England fall and prompted me to pull out my phone and do a quick Google search. I figured the University had to be having conversations about the building’s name, but wanted to confirm. Google did not disappoint. The very first result was an article by the Harvard Crimson noting that Harvard University President Lawrence Bacow found removing the Sackler name from campus buildings “inappropriate” as Arthur M. Sackler had passed years before Oxycontin was marketed to the public.1 While Harvard has chosen not to remove the Sackler name from its buildings, many other charitable organizations have, or have stopped accepting donations from the family, in an attempt to distance themselves from the conversations and litigations centered on the Sacklers’ role in the opioid crises.2 While a pertinent example, this is only one example of the conversations surrounding corporate philanthropy today.

It is an uneasy time for corporate philanthropy. On one hand, corporations are increasingly being called upon to respond to the challenges of the time — to get involved and do something about the struggles so many are facing every day. On the other, charitable organizations are increasingly being taken to task for accepting funds that are the result of horrifying business practices. Arguments about the balance between the benefits corporate philanthropy provides versus the harm corporations cause in order to acquire enough capital to be philanthropic have occurred for decades. But what do these conversations reveal about how power operates in the world of corporate philanthropy? What forms of power are made visible when we step back and consider not just the how of corporate philanthropy, but the why? And really, just what are the benefits of corporate philanthropy to the public if the goal of the public is justice?

This paper will begin to answer these questions by doing four things. First, it will provide a brief background history on the origins of corporate philanthropy in the United States. Second, it will discuss modern corporate philanthropy and situate modern corporate giving in today’s conversations about whether corporate philanthropy can ever create justice. Third, this paper will discuss the corporate tax code and describe how the tax code is integral to understanding the benefits, or lack thereof, of corporate philanthropy. Fourth and finally, this paper will discuss the “justice illusion” and how this illusion is at play when corporations engage in charitable giving. Overall, this paper aims to contribute to the conversation about if, and if so how, corporate wealth can result in community good.

INTRODUCTION

“I sit on a man’s back choking him and making him carry me, and yet assure myself and others that I am sorry for him and wish to lighten his load by all means possible . . . except by getting off his back.”3 In one sentence, author and philosopher Leo Tolstoy has summarized the state of corporate philanthropy today. Tolstoy is perhaps one of the best suited individuals to make this observation even though he passed away in 1910, decades before the modern era of corporate giving.4 Drastically influenced by his experience fighting in the Crimean War and observing other forms of state violence, Tolstoy became a fierce critic of war, excess profit, and excess power.5 One of Tolstoy’s most famous works, The Death of Ivan Ilyich, highlights Tolstoy’s perspective on the concerning profit-centric focus of modern society. In the novel, a wealthy judge who is on his death bed realizes that no one around him cares very much that he is dying. Instead, everyone, even his closest friends and family, is focused on how they might profit from his death. The Death of Ivan Ilyich speaks to the proposition that modern society is so intensely profit focused that no crevice of life, even those once consider sacred, can escape the requirement of creating capital.6

This same line of thinking can be applied to “doing good” in the modern day. Helping others has become big business. In 2019, corporate philanthropy accounted for $21.09 billion of all funds directed at social progress in t7he United States.8 Despite the high dollar amount donated by corporations, this giving is not as altruistic as it seems on the surface.

As the modern corporate model comes under increased critique, corporate charity has become a convenient rebuttal. Specifically, corporations can quickly point to the “good” they do under the current system with the implied suggestion that as corporations already “help” they should be allowed to continue to operate as they are currently — without regulation and significant oversight — lest they be forced to abandon their “good” works. This argument, that corporate good justifies corporations having the freedom to regulate themselves, symbolizes one form of deep capture — the capture corporations have over regulators, the public, and the public imagination about just how much good corporations can really do. By giving such immense dollar amounts to communities in need and organizations dedicated to addressing social issues, corporations can also soften the critiques they might receive from these groups. As these groups are some of the best positioned to speak about corporate harms, corporations benefit greatly from quieting their critiques with philanthropic dollars. In this way philanthropic giving not only boosts a corporation’s public profiles, it protects profit by softening criticism of the corporation and thus softening public pressure on regulators to change today’s corporate model.

Corporate philanthropy, and the public relations campaigns that accompany it, promote and sustain the dispositionist viewpoint that markets are the ultimate good by making it seem as if, even when society is at the mercy of the market alone people will voluntarily be taken care of by those with wealth. It paints regulation as bad by making it seem as if with regulation corporations would no longer be able to “help” people and thus people would suffer. To put it succinctly, corporations have leveraged corporate philanthropy to inure the public to a viewpoint that is particularly powerful for them — that government regulation interferes with social good rather than creating social good. Through this viewpoint, corporations have positioned themselves as “balls”, entities that go one way or another with no power over their direction, and left governments with all the responsibility of being “bats”, entities that have all the power to direct the balls.

This is how corporate philanthropy creates the illusion of justice. In this context, the illusion of justice is created when organizations with the public’s trust, such as governments or well-respected non-profits, legitimize corporations as entities working to address inequality. In this illusion it looks like organizations with the public’s trust are holding powerful entities to task, that these powerful entities are responding and working to address social problems, and that justice is occurring as a result. To best the justice illusion works when it comes to corporate philanthropy and what can be done about this the origins of modern American corporate philanthropy must be explored.

THE HISTORY OF CORPORATE PHILANTHROPY

The origins of corporate philanthropy in the United States actually begins outside of the corporate form and starts with wealthy individuals. In the wake of the industrial revolution, America’s wealthy found themselves called to a new mission — to leave their mark on the world by helping the public. This help could come in the form of a public theater, an investment into medical research, or simply writing sizable checks to local orphanages. It did not matter much what the help was as long as the donation was public and significant. One of the foremost texts about philanthropy in this age was the Gospel of Wealth by Andrew Carnegie.9 In the Gospel of Wealth, Carnegie, an American steel magnate, argues that it is up to the wealthy to determine how best to administer their funds to the benefit of the general public.10 In his own life, Carnegie used his wealth to establish free public libraries, colleges, and institutes for everything from teaching to peace-keeping.11 These donations reflect Carnegie’s philosophy towards giving that he repeats throughout his book— “the man who dies thus rich dies disgraced.”12 Yet, even with all his giving, Carnegie still embodies the same deep capture we see today.

Though his philanthropic efforts resulted in his peers and multiple governments legitimizing him as a master of public good, Carnegie’s business practices relied on perpetuating inequality. As a steel magnate, Carnegie depended on his workers living grueling lives. In the steel mills, workers often worked twelve hours a day, seven days a week and received just one holiday, the Fourth of July.13 In return for this immense labor, workers were paid approximately ten dollars per week, which would be about $13, 408 in annual income today. All of this occurred while Andrew Carnegie became one of the wealthiest men in history.14

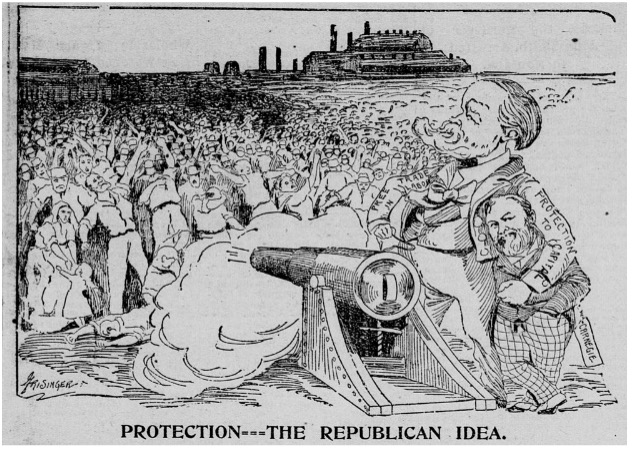

Figure 1 (Source: Unknown).

Figure 2 (Source: Unknown).

One specific moment in Carnegie’s history represents just how deeply his corporate and philanthropic works exemplify the justice illusion. In 1892, the union contract between the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers, the union that represented workers at Carnegie’s Homestead mill in Pennsylvania, and the Carnegie corporation was set to expire.15 The contract had only begun three years previously, in 1889, when a worker strike resulted in the corporation finally negotiating with their workers.16 Eager to get out of the contract and hire non-union labor, Carnegie encouraged his operations manager, Henry Frick, to do whatever he thought was necessary to break the union.17 Frick took to the challenge. First he cut the wages of workers. Then he locked them out of the mill. Next, he fired all of the workers. And finally, on July 6th, Frick hired three hundred Pinkerton agents to “protect” the plant.18 Workers came to the plant to protest their firing and re-affirm their strike. At some point, shots were fired into the crowd. To this day it is unclear which side opened fire first, but at the end of the day seven workers and three agents had been killed.19 In the wake of this fight, the Carnegie corporation had over one hundred strikers arrested and the union fell. The corporation immediately re-instituted longer hours, less pay, and worse conditions for its workers.20 And yet still, not seven years later, Carnegie un-ironically wrote the Gospel of Wealth arguing that it was the obligation of the wealthy to help society. Carnegie’s labor practices highlight that the philanthropy of the wealthy can create something that looks like justice all while these donors fight actual efforts for systemic improvements to society, such as better working conditions.

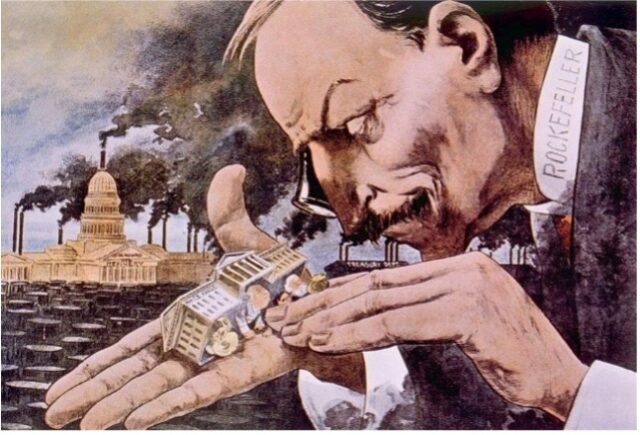

Figure 3 (Source: Unknown).

The charitable giving of another nineteenth century industry magnate, John D. Rockefeller, also highlights that the illusion of justice corporate philanthropy creates has long been see-through. At the peak of his wealth, John Rockefeller had a net worth of $280 billion, which was approximately 1.5% of the United States’ total yearly economic output at the time.21 Rockefeller acquired this immense fortune through the oil business. He co-founded Standard Oil in 1870 and this company eventually controlled over 90% of the United States’ oil industry.22 Standard Oil was able to gain this monopoly by demanding discounted rates from railroads, hiring men to spy on competitors, and forcing rivals to sell or be forced out of business.23 While all of these practices were technically legal at the time Rockefeller employed them, they still inspired conversations among the recipients of Rockefeller’s philanthropy that mimic the conversations about accepting funds raised through socially questionable methods many organizations are having today.

One of the most well-publicized of these discussions took place in 1905 over a $100,000 gift from Rockefeller to the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, an oversees missionary organization.24 Many people at the Board happily accepted Rockefeller’s donation, which would be worth approximately $2.7 million today.25 Graham Taylor, a minister, argued that “charitable gifts should be viewed as ‘separate from the person of its acquirer and possessor.’”26 Other proponents of accepting the gift argued that organizations should not be “afraid ‘of tainted money’” as it would be “better ‘for a missionary organization to have the money. . . than for Rockefeller to keep it for more nefarious purposes.”27

Figure 4 (Source: Unknown).

On the other side of the conversation was Washington Gladden, a pastor and early proponent of progressive Christianity. Gladden, an outspoken critic of major corporations for their role in the squalid living conditions of their workers demanded that the Board return the donation by arguing that “[n]o gift, no matter how large, could ‘compensate for the lowering of ideals and the blurring of consciences’ required to accept it.”28 Ultimately the Board accepted Rockefeller’s gift, but agreed not to take any future donations from similarly “controversial” figures.29

In this debate, Gladden cuts through the justice illusion created by corporate philanthropy by noting that good fruit cannot come from a rotten tree and urging the Board to pressure corporations to do good within their businesses, not just when they want to. The philanthropic endeavors of Carnegie and Rockefeller represent the long history of tension between corporate philanthropy, corporate practices and social good. As the philanthropy of the wealthy shifted from primarily being the purview of individuals and families to being the work of corporations themselves, the tie between a corporation’s philanthropy and its business practices became even stronger.

MODERN CORPORATE PHILANTHROPY

Renowned economist Milton Friedman once remarked that businesses that “take seriously its responsibilities for providing employment, eliminating discrimination, avoiding pollution, and whatever else may be the catchwords of the contemporary crop of reformers” are preaching “pure and unadulterated socialism.”30 Given this, Mr. Friedman might be horrified by the state of corporate philanthropy today. Barely a day goes by without a corporation putting out a tweet, statement, or email blast about their concern for a myriad of social issues and “what they’re doing” about them. On its surface, this seems like a far cry from the idea of shareholder primacy that is oft-discussed as the guiding principle of corporate business practices. Shareholder primacy is the theory that a corporation’s first and most important responsibility is to protect the interests of its shareholders. Thus, Mr. Friedman finds corporate philanthropy to be a form of “taxation without representation” as corporate executives are spending shareholder funds on causes that do not increase shareholders profits.31

But Mr. Friedman may find some solace in the fact that many corporations today are following the Carnegie and Rockefeller model of philanthropy. This means that today’s corporations are similarly acquiring wealth through socially harmful means while simultaneously being legitimated as socially beneficial actors through their corporate giving. In fact many corporations today are levering their good acts as a way to increase profit. This is a far cry from the “unadulterated socialism” Friedman feared.

In the 1980s and 1990s, corporations began to explicitly tie their philanthropic efforts to profit. They asserted that “. . .good corporate philanthropy incorporates both business interest and social needs” and this thinking remains the order of the day.32 For example, in the midst of the coronavirus crisis, tobacco giant Philip Morris International launched a campaign highlighting its donation of fifty ventilators to the Greek government through its Greek affiliate Papastratos.33 Papastratos has a 40% share in the Greek tobacco market.34 It is well documented that smoking tobacco can cause lung cancer, one of the most dangerous underlying disease to have if one contracts coronavirus.35 So, while Papastratos makes approximately €1.3 billion million per year selling products that, if used, make coronavirus significantly more deadly, it is also exclaimed for helping to fight coronavirus.36

One might ask what is the problem with this beyond donating too little. For example, if the company had donated ten thousand or one hundred thousand ventilators would that be a social good? The answer again lies with the justice illusion. Specifically with what society loses when it receives the illusion rather than justice itself. When corporations seem as if they are addressing social problems, calls for corporate regulation are dampened even if that regulation would result in greater social good. So, it is not just the size of the donation, but the larger effect of the donation, that is the problem.

The events of a different past tragedy, the economic crisis of 2008, might better exemplify this tension. Wells Fargo, one of the United States’ largest banks, was one of the many financial institutions that engaged in the misrepresentation of the risk and quality of mortgages it was selling, a practice that triggered the market collapse. With the collapse of the market came a tidal wave of individuals who lost their homes. At one point during the financial crisis, over eight million people lost their homes in a single week.37

Yet, despite Wells Fargo’s dismal history with housing in its corporate work, Welles Fargo is deeply engaged in housing charitable work. The bank is a long-time donor to Habitat for Humanity, one of the largest housing non-profits in the country. In fact, their Head of Consumer and Small Business sits on Habitat’s board.38 Wells Fargo has committed $1 billion to Habitat for Humanity, a fraction of what the company has made from its various bad acts, by 2025.39

Here again, the justice illusion and the corporate capture of “doing good” is on display. Major banks went basically unpunished by government for their role in causing the 2008 recession. Regulation resulting from this crisis often did not go very far and was short lived. And even at that time, when the justice illusion broke and it was clear that the entities legitimating businesses and businesses themselves were the general public, the power of these entities barely wavered. Now some, like Welles Fargo, are further cementing that power by improving their public image through working to solve the same problems they created.

Even more concerning is that through philanthropy corporate entities have been able to get legitimizing institutions to cement this power for them without having to do it themselves. For example, in 2011 AT&T and T-Mobile attempted a hotly contested merger.40 The Antitrust Division of the United States Department of Justice announced that it would attempt to block the takeover and the proposed merger landed in front of the Federal Communications Commission.41 So, the NAACP, Gay & Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (GLAAD), homeless shelters, and the Asian Pacific Islander American Scholarship Fund all submitted comments in support of the merger.42 While at first glance these do not seem like groups that might be heavily invested in a telecommunications merger, each group had received tens of thousands of dollars in charitable donations from AT&T.43 Though the merger eventually fell apart for other reasons, this action by such large and influential socially focused groups, like the NAACP and GLAAD, could have lent significant credibility and acceptance to a business decision with little analysis as to the social impact of the decision.

A study by Marianne Betrand, Matilde Bombardini, Raymond Fisman, et. al. titled “Hall of Mirrors: Corporate Philanthropy and Strategic Advocacy” has found that corporate donations to a nonprofit result in a “two-to-four-fold increase in the likelihood that the nonprofit group will comment on [a] same proposed rule as the firm.”44 How can nonprofits continue to be stewards of social good when they rely so heavily on actors that profit from social bad? Are there any other ways corporations leverage their charitable “good” into corporate benefits? If so, how does this effect the public good done through corporate charity? These are some of the questions that continue to linger when considering the relationship between corporate power and social good today.

CORPORATE PHILALNTHROPY AND THE TAX CODE

One body of law integral to understanding these lingering questions is the tax code. This code sufficiently highlights that a corporation’s “charitable” acts benefit the business itself. Like the history of corporate philanthropy, the chronicle of corporate philanthropy and the tax code begins with wealthy individuals. The federal income tax was created with the passage of the 16th Amendment in 1909.45 Prior to the passage of the 16th Amendment the federal government had been largely reliant on excise taxes, which disproportionately came from the poor. But, as the number of incredibly wealthy Americans and the amount of their wealth ballooned in the early 1900s, the federal government faced immense pressure to expand its tax base.46 At first less than 1% of households were subject to income tax and it applied to a miniscule amount of income.47 But in the 1910s the need to raise funds for the United States’ participation in World War I resulted in a growth of the federal income tax and eventually in a top tax rate reached 67% in 1917.48 In that same year, Congress added a deduction for charitable donations by individuals because “of worries that reduced after-tax income of the very rich would end their philanthropy, shifting burdens the philanthropists had been carrying onto the backs of a wartime government.”49 In this way, the federal government explicitly described the charity of the wealthy as a substitute for federal action on social welfare.

Corporations gained the ability to deduct their charitable contributions from their federal taxes in 1935.50 With this came a new possibility for ensuring profit growth and corporate control. Now, wealthy individuals and families could sell shares of their corporations to the family foundation. With the shares centered in one entity, the foundation, families could continue to vote as a block and ensure continued control over the corporation. To add a cherry to the top of this sundae of benefits, since foundations are untaxed, wealthy individuals that sought to transfer their wealth to their offspring could circumvent the estate tax by leaving the funds and shares with the foundation and the foundation in the control of their children. Without this ability, “meeting the costs of the estate tax might have force[d] a family to sell shares below the 51 percent level of corporate control.”

The number of benefits wealthy individuals and corporations could accrue from creating charitable organizations eventually garnered such criticism that Congress passed the Tax Reform Act of 1969, which increased federal oversight of nonprofits.51 After the passage of the Tax Reform Act philanthropy by the extremely wealthy reduced significantly. Families “in the top 0.1 percent of the income distribution reduced the share of income they donated by half from 1980 to 1990, concurrent with the reduced value of the deduction over that period.” Here again, corporate philanthropy is revealed to be an illusion of justice and a practice primarily concerned with corporate profit, not social benefit.

CORPORATE PHILANTHROPY, CORPORATE POWER, AND THE ILLUSION OF JUSTICE

The tax implications of corporate philanthropy raise the question of who and what does corporate philanthropy really serve. One macro script justification for the continued minimal regulation of corporations is that the market will protect all stakeholders on its own.52 Corporate philanthropy takes this macro script a step further and asserts that it is not just the passive protection of the market that keeps society, but the active interest of corporations as well. As corporations do “good” —donate ventilators in a health crisis and build homes in a housing shortage — it appears that the market is doing exactly what the macro script says it will — ensuring that all stakeholders in the market are provided for. The tax code codifies this protection by creating market incentives for corporations to “do good.” But the good done by corporations often comes at the expense of the greater good that can be done by corporate regulation. As Congressmen noted when discussing increasing the federal income tax, the philanthropy of the wealthy has long been seen as a substitute for government action. As the country continues to reel from social issue after social, many of which are directly contributed to by corporation, this weak substitute can no longer stand.

But who is to make this push for regulation? Many of the entities best positioned to challenge corporate power also rely on corporate philanthropy to support their work and their staffs. So, what is to be done and who should be doing it? Two actions exemplify the first steps that can be taken. First, the federal government must lead the charge for tackling social problems through regulation rather than through the voluntary charity of the extremely wealthy. As noted by the changes in charitable giving that occurred after the passage of the Tax Reform Act, the benevolence of the rich is not a sustainable solution to endemic social issues. Greater regulation, such as an increased minimum wage, mandatory benefits for all employees, and greater oversight over corporations to prevent wage theft, is necessary to address many of the factors contributing to the financial struggles of so many Americans today. Second, regulation needs its own public relations campaign. Corporate philanthropy has done an excellent job of marketing itself to the public as a good thing. Government regulation has not done the same. To garner support for increased regulation, the public must be able to see that regulation will result in greater social benefit than corporate charity. This message is not an easy one to get across, especially when corporate giving comes with such fanfare and significant dollar amounts, but it is necessary to begin to peel back the layers of the macro script and the justice illusion that keep corporate power cemented in place. As social turmoil continues to multiply, let us hope that these changes and conversations around philanthropy and justice continue so that ultimately corporate giving is replaced with thorough social good.