INTRODUCTION

On July 22, 2013, Turkish scholar and social media expert Zeynep Tufekci tweeted “Last year, I pondered the first ‘social-media fueled ethnic cleansing.’ With ethnic tensions & expanding online hate speech, is it Burma?”1

In 2013, Myanmar was in a period of rapid democratization. The world was optimistic for a bright future in the country. But Tufekci’s tweet was prescient. In 2018, a United Nations Report documented genocide in Myanmar, and directly attributed to Facebook a “significant” role.2

At the time of the writing of this paper, political turmoil in Myanmar has escalated. A recent coup d’état has shattered any lingering dreams of democratization, and the UN reports that the country is “approaching the point of economic collapse.”3 Meanwhile, very little has changed for Facebook. International frameworks for corporate accountability have created a situation where Facebook, which engaged in vastly destructive behavior, will see no legal consequences for its role. This paper is a story of what happened in Myanmar, and why it is likely to happen again.

History and Background

Colonial and Military Rule

The history of ethnic conflict in Myanmar4 can be traced to British colonial rule.5 Beginning in 1842, the British used artificial lines of division to consolidate their hold on power,6 elevating minority groups and disempowering the religious majority, a Buddhist population known as the Bamar.7 Though the religious and ethnic composition of the country is complex, this paper will focus on relations with Muslim-majority group known as the Rohingya, centered in the northern Rakhine region of Myanmar. This region’s proximity to Bangladesh, along with seasonal migration, created a narrative of the Rohingya as “foreigners,” a narrative fostered by the British8 and with a destructive legacy that persists in the present conflict.9

In 1948, Myanmar gained its independence.10 A transitional period of optimism quickly waned with the assassination of democracy advocate General Aung San (father to current-day leader Aung San Suu Kyi).11 The majority-Buddhist military, known as the Tatmadaw, quickly rose to occupy power, grounding its ruling legitimacy in opposition to the country’s many ethnic minorities. 12

White the military’s ethnic nationalist policies have targeted many groups, the Rohingya of Rakhine have been specifically attacked. Legislation has denied them citizenship and other basic rights, 13 and they have been repeatedly victim to incidents of mob violence, often with state support. 14

Democracy and Liberalization

Starting in the 2000s, the military began taking positive steps to relinquish its chokehold on Myanmar’s political institutions. Though the motivations for liberalization are contested, the trend was real. A 2008 referendum on a new draft constitution generated overwhelming support, and in 2010 the country held elections that resulted in a shift in power away from the Junta towards a nominally civilian government.15 Though the military retained significant powers, the election was heralded as a breakthrough for democracy in Myanmar.16

President Thien Sein assumed office in March 2011. He immediately took steps to break from repressive policies of the Junta, reaching out to opposition parties and leader Aung San Suu Kyi, and seemingly tolerating an increased level of protest and freedom nationally.17 The world took notice. In 2012, President Obama became the first ever American President to visit the country, telling reporters, “this process of reform. . . is one that will move this country forward.” 18

Among the steps applauded by international observers was the opening of Myanmar’s telecommunications spaces. Though the internet has existed in some form in Myanmar since the early 1990’s, access was tightly restricted and draconian laws tightly regulated speech critical of the regime.19 The telecommunications sector was liberalized in 2014, after legislation paved the way for international companies to begin establishing infrastructure, 20 along with the repeal of some censorship laws.21

By mid-2016, over 43 million sim-cards had been sold by various telecom companies, in a country of roughly 54 million people. This represents a dramatic and rapid shift in the country towards widespread access to the internet, with the majority of that access concentrated in the mobile sector. Myanmar was a highly attractive market for foreign technology companies, with a population of millions, consumption and leisure patterns shifting rapidly online, and no entrenched domestic competitors.22

Of all the internet companies to move into Myanmar, Facebook was by far the most successful. Facebook quickly emerged as the primary platform for online interactions in the country.23 For many of its roughly 20 million users, the site serves as “their main source of information.”24 Facebook’s dominance is widely recognized. As the Chair of the UN Fact Finding Mission noted, “As far as the Myanmar situation is concerned, social media is Facebook, and Facebook is social media.”25 By 2013, nearly the entire internet-using population of Myanmar had a Facebook account.26

The dominant narrative surrounding Facebook’s entry into Myanmar was one of overwhelming optimism. The changes in Myanmar seemed to parallel movements in other parts of the world. At around this time, mass protests in the Middle East, known as the Arab Spring, were being driven in part by social media, providing activists new access to political information and tools to coordinate outside the watchful eye of governments.27

The narrative of open communication facilitating political liberalization and opportunity is a familiar one to many Americans.28 Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook’s founder, describes the product as more than a tool for advertising revenue, but as a corporation with a “social mission” to “make the world more open and connected.”29

These values were easily exported to Myanmar by American tech giants. In 2013, Eric Schmidt, then CEO of Google delivered a speech with a clear message. “Try to keep the government out of regulating the internet,” he told a group of students. “The internet, once in place, guarantees communication and empowerment becomes the law and practice of your country.”30 Of course, Schmidt was not merely motivated by democratic values. With respect to information technology infrastructure, he noted, “If we [build it] right, within a few years the most profitable businesses within Burma will be the telecommunications companies.”31

Genocide

Schmidt and Zuckerberg may have been right about the profitability of online business in Myanmar, but they were shockingly off the mark when it came to the influence of the internet on the political and social fabric of the country. Despite global optimism for a post-Junta Myanmar, the situation in Rakhine soon sharply deteriorated.

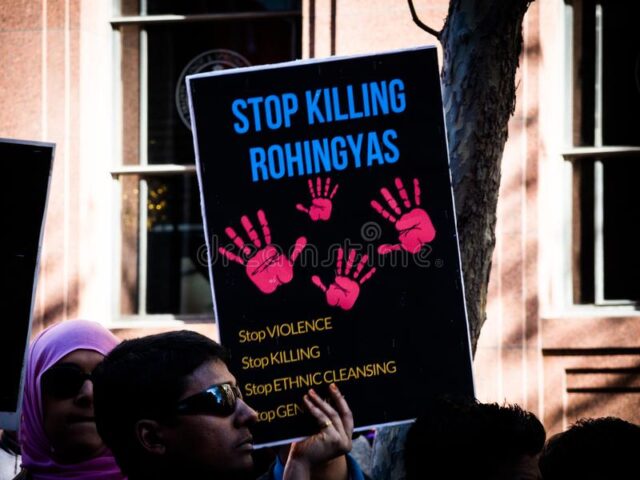

Waves of state sponsored32 violence began to escalate in 2012, with a mob killing a group of Muslim pilgrims in Rakhine following a deliberate “campaign of hate and dehumanization of the Rohingya [that] had been under way for months. . .”33 Ultimately, over 140,000 people were displaced. 34

The simmering tension exploded in August of 2017. A Rohingya militia, known as the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) launched an attack on various military installations in the north, killing twelve security personnel. The military response was “immediate, brutal and grossly disproportionate.”35

Security forces launched what they termed “clearance operations.” The UN’s reporting leaves little room to avoid the conclusion that these operations were, in fact, genocide.36 Over 10,000 Rohingya were killed, often in mass. Entire villages were burned to the ground. 37 Rape was systematically deployed on a massive scale. The conditions permitting such a response were generated by the narratives formed over the previous century and a half. With ethnic minorities cast as non-citizen immigrants posing a threat to the nation, the ARSA provocation provided sufficient justification for systematic murder of thousands.

Facebook’s Role

Facebook and Extremist Speech

The climate of ethnic tension was a key contributor to the atrocities of 2017, and Facebook hosted a shocking quantity of extremist speech on its platform. The platform permitted and facilitated violence in three ways.

First, Facebook facilitated peer-to-peer interactions which affirmed and entrenched hateful narratives targeting Rohingya. One NGO study of online speech leading up to the genocide identified a crystallized narrative that took hold on Facebook.38 Citizens were identified as under threat from violent Muslim “foreigners,” who aimed to displace and overthrow the Buddhist majority. The military was coded as a national savior, and the only force capable of protecting the integrity of the nation.39 The proliferation of degrading and dehumanizing language was staggering, with thousands of examples of Facebook posts referring to Rohingya as “dogs,” “maggots,” and “rapists” who ought to be “fed to pigs” and “exterminated.” 40 The sheer quantity of these posts attests to the failure of Facebook to craft and enforce an effective moderation policy for the country. 41

Second, Facebook played host to a massive misinformation campaign originating with the military. Some months after the UN noted Facebook’s role in spreading hate, reporting from the New York Times and others found that many seemingly unrelated entertainment, wellness, or celebrity accounts were in fact military sock puppets.42 Accounts with names like “Lets Laugh Casually” or “Down for Anything” were, in fact, military fronts seeding hate.43 Activity spiked in 2017 during the run up to the genocide.44 Facebook reported awareness at the time, but did not investigate the military and failed to remove any of the accounts until third party reporting drew awareness to the problem.45 Facebook concedes that these accounts clearly violate their terms of service requiring authenticity. The failure to detect these obvious vectors of misinformation suggests significant failures of enforcement.

Finally, Facebook hosted specific hateful messages which were intended to directly incite violence—and succeeded. One widely cited incident involves extremist monk U Wirathu, who posted about a rumor of an alleged rape of a Buddhist girl by “Bengali-Muslim” men. In the days that followed, a “seemingly coordinated riot” occurred in the region of the alleged incident, resulting in the deaths of two local activists.46

The Dominant Narrative of What Went Wrong

Roughly a half-decade later, observers have come to a remarkable consensus about what went wrong with Facebook in Myanmar. Reporting from the United Nations fact finding mission, coupled with observations from scholars and civil society paints a comprehensive picture of how Facebook’s entry into Myanmar contributed to genocide.

Remarkably, Facebook agrees. In 2018, the company commissioned an “independent human rights impact assessment” on its impact in the country. The report, by the non-profit “Business Social Responsibility” (BSR), reaches the bottom line finding that Facebook was not “doing enough to help prevent our platform from being used to foment division and incite offline violence.”47 The consensus account of why Facebook failed, shared between this report and other sources, may be termed a “dominant narrative” of what happened when Facebook came to Myanmar. Three contextual factors are repeatedly cited in explaining the prevalence of online hate speech.

First, the BSR Report notes that the rapid expansion of internet access caused a problem related to the “digital literacy” of the population.48 The report notes, “Before 2013, and after decades of state control, Myanmar was a rumor-filled society at every level, and free speech was virtually non-existent.”49 The implication is that the population of the country was uniquely vulnerable to any disinformation circulated online, with users naively believing that Facebook is a reliable source of information.50

Second, many observers note the immense technical challenges associated with moderation in Myanmar. The country does not adhere to an important global technology standard known as Unicode,51 which Facebook claims made it impossible to implement its moderating tools.52 Moreover, specific cultural knowledge is required for effective moderation in Myanmar in order to separate threats from idiom. For example, following a spate of violence extremist Buddhist monk U Wirathu posted a warning to Muslims to “eat as much rice as you can.” This was a veiled threat, the implication being that his enemies would not be around much longer, to eat rice or otherwise.53 Facebook claims that growing its team of Burmese-speaking moderators will help it moderate in the future.54

Third, the BSR report notes that Myanmar was a challenging environment in which to operate, given deep social divisions and a government that disdains human rights. In particular, “there are deep-rooted and pervasive cultural beliefs in Myanmar that reinforce discrimination and which result in interfaith and communal conflict. . .” thereby elevating “Facebook’s human rights risk profile.”55 The BSR report identifies pre-existing narratives and the tendency for those narratives to be advanced by powerful actors as creating a situation where hate speech exists, regardless of the platform. As civil society reporting has noted, “Hate speech in Myanmar is not simply the product of individual bigotry. . . [r]ather, hate speech has been systematically promoted and disseminated by powerful interests that benefit from the constructed narratives and the resulting division and conflict in society.”56

This summary of the dominant narrative simplifies the factors contributing to hate speech on Facebook, providing a powerful picture of how Facebook found itself used as a tool in a long running conflict. The story is summarized aptly in a quotation from the BSR report. “Facebook isn’t the problem; the context is the problem.”57

Criticizing the Dominant Narrative

The dominant narrative hardly absolves Facebook of blame in Myanmar, yet it fails to adequately capture the company’s culpability. Facebook’s self-assessment pervasively emphasizes the role of situational factors which resulted in harms. When BSR names “the context” as the problem, it subtly but clearly downplays Facebook’s own agency. That is, Facebook is understood to be “an object moved by something in its situation,”58 and not as itself an agent with the ability to freely choose to pursue its own stable preferences over time.

Remarkably, this vision of Facebook is widely shared. The company’s role in the Myanmar genocide received a flurry of attention after it was explicitly named in the UN Fact Finding Mission as playing a role in the escalation of violence. That report described Facebook as a “useful instrument” for hate speech, a framing that “by using the passive voice. . . obscured the platform’s agency and avoided the attribution of legal responsibility to Facebook as a company engaged in the business of content moderation.”59

Framing Facebook as a passive actor in Myanmar distorts reality. In 2017, Facebook reported more than USD$27 billion of revenue, making it, at the time, one of the 100 largest corporations in the world.60 Meanwhile, the per capita GDP in Myanmar was measured by the World Bank at less than USD$1,500.61 Any policy choices adopted by the company were not for lack of capacity.

Despite this, Facebook devoted close to zero resources to content moderation. As late as April 2018, well after Facebook was aware of the scope of the problem and the harms that resulted, civil society organizations reported that basic moderation functionality like the ability for users to “report” harmful messages within certain Facebook apps was completely missing.62 Even more troublingly, Facebook had hired no Burmese speaking staff to whom dangerous messages could be reported.63 And despite promises to consult with local stakeholders to develop processes to prevent future outbreaks of violence, those organizations reported no direct consultations, and no feedback in response to their proffered suggestions.64

Facebook’s inaction was not merely a result of inattention or unfamiliarity with a foreign market. The problems reported in Myanmar were familiar ones, albeit with far more dangerous and violent stakes. By 2017, two general problems associated with Facebook’s business model were already clearly established.

First, social media has a tendency to create polarizing “echo chambers.” Facebook gives users unprecedented control over the information that they access reinforcing a tendency to seek out only sources with which users already agree. As a result, users are exposed to a narrow spectrum of information, which tends to increase polarization and extremism. By 2017 this phenomenon had already been well documented on Facebook.65 Unsurprisingly, Myanmar was particularly susceptible to the echo chamber effect,66 suggesting that Facebook was driving increasing polarization in the country just as violence escalated.

The second problem is Facebook is an effective vector for the spread of misinformation. This activity was very well understood in 2017, as post-mortems of the 2016 U.S. presidential election focused on the role of “fake news” in politics, and the importance of social media in its proliferation.67 In Myanmar, the military took advantage of Facebook to seed harmful and false narratives about threats from Rohingya, ultimately justifying their violent campaign of repression.

These problems were not unknown to Facebook. But to address them threatens the fundamental values of the corporation—the need to add users in order to grow. Echo chambers and misinformation drive violence, but they also are a consequence of, and in turn drive, user engagement. This fundamental tension at the heart of Facebook’s business model has been known to its management since before the genocide. It is put most starkly in a leaked memo from former Facebook Vice President Andrew Bosworth. He wrote “We connect people. Period. That’s why all the work we do in growth is justified. . . That can be bad if they make it negative. Maybe someone dies in a terrorist attack coordinated on our tools. And still we connect people. The ugly truth is that we believe in connecting people so deeply that anything that allows us to connect more people more often is *de facto* good.”68

Facebook knew it was selling a dangerous product, and entered a dangerous market without doing the bare minimum to protect its users. In that light, it seems obvious that the “context” isn’t the problem. Facebook is the problem.

Corporate Law and Accountability

Facebook concedes that its product caused harm in Myanmar. Taken together with the vast magnitude of the damage caused, one might think that this is an easy case for corporate accountability. Unfortunately, that door is firmly shut. No existing legal mechanisms could plausibly be used to hold Facebook accountable, reflecting a longstanding gap in international law when it comes to punishing corporate malfeasance. There are tricky questions about just how liable Facebook should be, as a platform, when it comes to user speech, but the accountability gap is so wide that these questions will never be broached in a legal context. Jurisdictional barriers will suffice to keep Facebook out of court.

Domestic Legal Remedies

Before turning to international frameworks to address cross-border corporate harm, it is worth examining whether any relevant domestic legal systems may offer a remedy. In this case, the prospect of a justice being served by Myanmar courts is easily ruled out, and the recent coup underscores that point.

Accountability is more likely in the courts of the United States, but it remains a dubious prospect. From the earliest days of the republic, American law has provided foreign nationals the opportunity to sue for torts committed abroad, via the Alien Tort Statute.69 Unfortunately, in 2021, accountability through this mechanism is vanishingly unlikely. Setting aside the practical barriers of finding a victim with standing, the Supreme Court has spent the past decade methodically gutting the applicability of the ATS to cross-border corporate activity.70 While the question of whether an American corporation may be held accountable for harms abroad is technically still open, the trend in the Court’s jurisprudence is clear. Compounding matters, the American law governing social media platforms generally holds that publishers of third-party information are not liable for harms arising from that content.71

International Law and International Criminal Law

Given that domestic law cannot provide a remedy, advocates may turn to international law in search of accountability. They are unlikely to find it. In general, international law does not account for corporate malfeasance because the law is centered around states, and only states are capable of being held liable for any breach.

For scholars and international jurists, the shortcomings of this scheme have long been apparent, particularly as regards the worst categories of international criminal acts. In order to overcome this problem of impunity, one of the major innovations of international law in the 20th Century was the development of an international criminal legal regime, culminating in the ratification of the Rome Statue of the International Criminal Court in 2002.72

The ICC’s jurisdiction extends to criminals with responsibility for perpetrating a range of international crimes—including genocide. Although neither Myanmar nor the United States are States Parties to the treaty—a problem because the ICC’s jurisdiction extends only to the territory and/or citizens of States Parties—the Court has recently suggested it may possess jurisdiction given impacts on neighboring Bangladesh.73 Thus in general, the ICC is the mechanism most likely to bring accountability to any party responsible for violence, including Facebook.

Unfortunately, early in the drafting of the ICC treaty, Corporations were exempted from the court’s jurisdiction. Negotiators explicitly considered, and rejected, extending liability directly over corporate entities that committed, or were complicit in committing, crimes against humanity.74 In contrast, individual corporate officers may be held liable, but it must be established that they acted with “intent and knowledge,” a very difficult bar to clear. 75 Facebook will not be on trial at the Hague any time soon.

International Human Rights Law

The most robust innovations targeted towards corporate conduct in international law are taking place in the space of human rights. Human rights law, through a robust and growing system of treaties, offers individuals protection against state violations. These treaties are directly relevant to the situation in Myanmar—among the first human rights treaties adopted was the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.76

It is no coincidence that the BSR Report Facebook commissioned spoke in the language of human rights. The conversation surrounding corporate responsibilities in the human rights space is as old as human rights treaties themselves.77 That being said, despite significant energy and attention in recent years, human rights treaties remain constrained by the scope of public international law itself—they act directly only on states. Recent diplomatic efforts have led to a proliferation of voluntary instruments, including the United Nations Global Compact and the Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, but no existing treaty can enforce legal claims directly against Facebook for their role in Myanmar. And while an instrument that would impose direct legal obligations on corporations is currently under discussion at the UN, its pathway to becoming law is long and uncertain.

International Commercial and Investment Arbitration

It would be easy to deduce that international law is simply an inappropriate mechanism for corporate accountability. However, when it comes to protecting corporate interests in international law, States and corporations have had no difficulty devising a system that holds corporations accountable—when it suits them.

The New York Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards is a treaty negotiated by states that supports a robust and highly lucrative system of international commercial dispute resolution—largely between corporations themselves.78 Meanwhile, starting in roughly the late 1990’s, a trend in investment treaties created a new system of international investment arbitration, permitting corporations to hail governments themselves into international tribunals—bypassing those states own domestic courts. This system permitted, for example, Phillip Morris to sue the governments of Australia and Uruguay for imposing regulations on tobacco packaging.79 Though those actions were ultimately unsuccessful, they do provide a sort of mirror image to the picture of human rights accountability, where corporations can successfully evade nearly all liability.

In international law, there is a vast gulf between legal regimes which serve to hold corporations accountable, and those which exist merely to serve corporations. The forces that permit corporations to shape domestic law to their liking also help them influence the priorities of international negotiators creating these instruments. The result is an international system that cannot hold corporations accountable.

CONCLUSION

Facebook’s entry into Myanmar provides a vivid picture of how corporations behave in an absolute lacuna of legal accountability. Facebook knowingly sold a product that tended to exacerbate political divisions and spread misinformation, and did so in a market with significant pre-existing risk factors. It adopted no mechanisms to mitigate those harms, failing even to enforce its own voluntary standards. In so doing, Facebook helped facilitate a genocide.

The level of Facebook’s culpability is debatable. A good case could be made that it was negligent or even reckless in its Myanmar operations. But the company’s own response, conceding that it bears some level of responsibility, suggests that this legal debate is an academic one. Facebook does not fear any repercussions outside of negative public relations. As such, no external forces are shaping its future behavior.

Facebook says that it will do better. In radio interviews80 and testimony before Congress, 81 Mark Zuckerberg has pledged to make changes. The corporation has done a post-mortem on its role, and outlined specific steps that it claims will help.

But the source of the harm is deeper than a lack of preparedness and the unique context of Myanmar. Serious questions persist about whether Facebook’s very business model will make a repetition of the Myanmar genocide inevitable.

In April 2021, at the time of this paper’s writing, the Guardian reported on a trove of internal documentation demonstrating the company’s knowledge of politically manipulative behavior by authoritarian leaders. Sophie Zhang, a former data scientist and whistleblower, documented “blatant attempts by foreign national governments to abuse our platform on vast scales to mislead their own citizenry.”82 These are new abuses, coming after the platform’s experience in Myanmar.

One week after Ms. Zhang came public, the New York Times published a deeply reported piece on ethnic tensions in Sri Lanka. The report tells a story of Facebook news feeds dominated by ethnic stereotypes and communal hatred. It recounts an anecdote of a shop overrun by a mob after false rumors spread on a Facebook news feed.83

Facebook helped facilitate a genocide in Myanmar, and it will not be held legally accountable. The only check on Facebook’s future behavior is Facebook. “There is a lot of harm being done on Facebook that is not being responded to because it is not considered enough of a PR risk to Facebook,” Ms. Zhang told the Guardian, “The cost isn’t borne by Facebook. It’s borne by the broader world as a whole.”84 Without international mechanisms for corporate accountability, those costs will continue with no end in sight.