INTRODUCTION

Following George Floyd’s killing at the hands of police in 2020, Coca-Cola Company, headquartered in Atlanta, Georgia, took a strong stance on the Black Lives Matter protests and committed to confronting racism in their company and in the community, stating: “As a company that believes diversity and inclusion are among our greatest strengths, we must put our resources and energy toward helping end the cycle of systemic racism.”1

Figure 1: Excerpt from “Where We Stand on Social Justice,” June 2020 (Source: Coca-Cola Company).

Figure 2: Excerpt from “Where We Stand on Social Justice,” June 2020 (Source: Coca-Cola Company).

Less than a year later, on the eve of the Georgia state legislature passing one of the most restrictive voting bills since the Jim Crow era, Coca-Cola remained silent. Religious leaders and voting rights activists were outraged and demanded action. Bishop Reginald Jackson, the head of a large AME church in Georgia, told Axios, “[If] Coca-Cola wants Black and brown people to drink their product, then they must speak up when our rights, our lives, and our democracy as we know it is under attack.”2 Georgia’s bill was signed into law on March 25, 2021, and Coca-Cola eventually succumbed to public outrage and released a statement voicing their opposition to voter suppression legislation.

In times of crisis, when our civil rights are on the line, we often turn to business corporations to address injustices without understanding the role they have to play in creating it. But why? Why do change-makers, activists, and social justice organizations continue appealing to corporate power despite the history of corporate inaction in the face of injustice? Business corporations have engaged in a decades’ long campaign that positions them as legitimate actors in the fight against injustice while fiercely protecting their interest in promoting business-friendly solutions to social issues:

“[E]lites have spread the idea that people must be helped, but only in market-friendly ways that do not change the underlying economic system that has allowed [them] to win and fostered many of the problems they seek to solve.”3

But as business corporations have gained more power, they have begun to compete with nonprofits. In addition, changes in corporate law have tilted the power balance toward profit-seeking corporations, further putting nonprofits at a disadvantage.

Today, we’re at an inflection point, where nonprofits will either continue to operate on the defensive and further entrench themselves within the corporate grasp, or go on the offensive and work to reassert their value and usefulness as a counter to corporate intervention in social problems.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Foundations of U.S. Philanthropy and Charity

The history of organized philanthropy and charity in the United States dates back to the 1700s, when colonists formed structured entities such as fire departments, orphanages, and hospitals to address social needs.4 These nonprofit corporations filled a crucial gap in the social welfare of the new country.5 Nonprofits grew to encompass a variety of missions, ranging from service-based organizations such hospital systems, housing initiatives, and food banks, to member-serving organizations such as labor unions and civil rights organizations.6

Nonprofits are generally funded by private foundations, government grants, and individual donations. The oldest foundations in the country, organized as charitable trusts, were funded by the generational wealth accrued by corporate executives involved in industrialization.7 In addition to foundation funding, nonprofits have continued to receive a bulk of their funding from government grants, so much so that “the modern welfare state [was largely] subcontracted to nonprofits.”8

Neoliberalism and Government Deregulation

“The ascendance of conservative political elements in the 1980s and beyond brought with it a conscious effort . . . to encourage government program managers to promote for-profit involvement in government contract work instead, including that for human services.”9

The rise of neoliberalism ushered in the “deregulation, privatization, and the withdrawal of the state from many areas of social provision,” and promoted the idea that “each individual is held responsible and accountable for his or her own actions and well-being [extending] to realms of welfare, education, health care, and even pensions.”10 While pushing for federal deregulation, corporate powers vied for more sway within the government itself.11

From the neoliberal movement came expansive deregulation. In the 1980s, President Ronald Reagan restricted the flow of funds to social programs, especially in the areas where federal support of nonprofit organizations was most widespread— social and human services, education, community development, and nonhospital health care.12 Reagan’s ascendency promoted the idea that business, not government, were the appropriate entity through which to address the country’s biggest problems.

The Rise of Corporate Social Responsibility

Corporations stepped into the vacuum of deregulation and privatized government programs, and began engaging in work previously delegated to nonprofits, often justified by the narrative of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). 13

As a practice, CSR concerns the social and environmental obligations of business corporations toward the broader public.14 CSR is often understood as a worthwhile endeavor that leads to more profits and increased “trust, legitimacy, and goodwill.15”

Figure 3: After implementing a $15/hr minimum wage, a cartoonist for the Seattle Times portrayed Amazon as aligned with the values of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., even as Amazon engages in union-busting practices and harsh working conditions.16 (Source: Vice).

Today, business corporations rely on CSR to promote the narrative that they are best suited to address major issues of injustice by prioritizing the marketplace ideology that rewards profit-seeking behavior.

Nonprofits at The End of The 20th Century

After the governmental austerity of the 1980s and 1990s, nonprofits turned to private sources of income to keep up revenue, while altering the way they spoke about their work. 17 With restructured government funding, nonprofits altered the way they pursued their missions while vying for resources and competing with new, for-profit entities who pushed the idea that they could more effectively address social issues.

THE ROLE OF CORPORATE LAW

Corporate law perpetuates a power imbalance in the overregulation of nonprofits compared to business corporations. Different standards and responsibilities are created and perpetuated by our court system and influenced by outdated notions of the purpose of nonprofits. Laws around the creation and legal protections afforded to corporations are heavily skewed toward rewarding profit-seeking behavior. This prioritization leaves nonprofits in a disadvantaged position as business corporations continue to encroach on the nonprofit sector.

What is a nonprofit?

Nonprofits are corporations. As a legal entity, they are often misunderstood or mischaracterized by the general public, much of which can be attributed to the misnomer “nonprofit” itself. Nonprofits are allowed to make profits. But unlike business corporations, they cannot issue stocks and they are prohibited from distributing their profits to those who exercise control over it, such as directors, officers, or members.18 Any income earned can go to paying for employee compensation, labor services, capital projects, or programs that further the nonprofit’s mission.

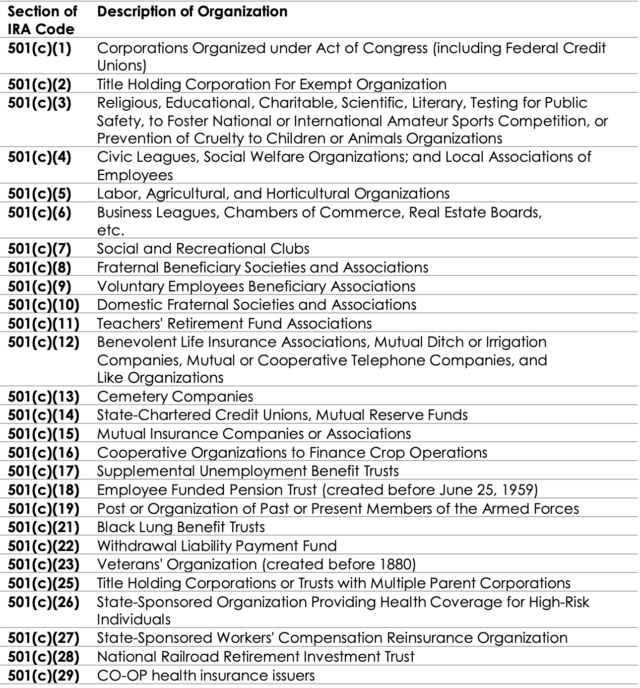

There are 27 nonprofit designations under section 501(c) of the Internal Revenue Act.19 The most common nonprofits are organized under Section 501(c)3 of the Internal Revenue Code, which is reserved for charitable organizations established for purposes such as education, religion, or charity.20 In order to maintain tax-exempt status, the organization must have the oversight of a board, a founding charter, and refrain from engaging in political advocacy.

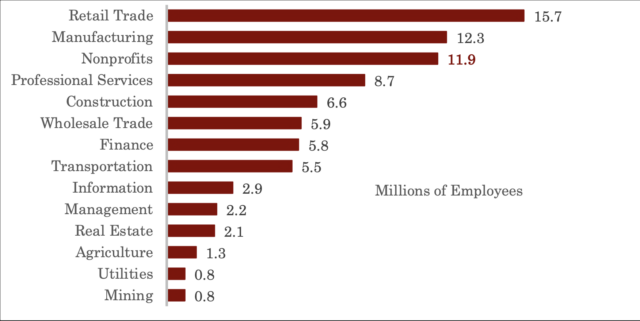

The nonprofit sector today employs nearly 12 million people in the United States, making it the third largest industry behind retail and manufacturing.21 In 2016, nonprofits contributed an estimated $1.047 trillion to the US economy.22 Based on IRS filings from the same time period, there were 1.54 million registered nonprofits.23

Figure 4: Employment in the Nonprofit Sector vs. Major U.S. Industries, 2015 (Source: Johns Hopkins Center for Civil Societies).

But for all their impact and influence, nonprofits are beholden to corporate law structures that keep them inherently weaker than their business counterparts, which is influenced by outdated notions of charity and intentionally vague theories of appropriate governance and liability.

Shareholders and Stakeholders

The starkest disparity in applying corporate law to nonprofits is the dissonance between the value shareholders and stakeholders. Courts have embraced the standard of shareholder primacy as the backbone of corporate law, while haphazardly applying shareholder norms to nonprofit corporations.

Much of nonprofit corporate law is borrowed, oftentimes ineptly, from corporate law and modified to fit nonprofit structures. For example, nonprofit structure requirements are controlled at the state level, but many state statutes “simply substitute the word ‘members’ for ‘shareholders’ where the corresponding business-corporation statue would give oversight rights to shareholders.”24 There have been efforts to create model nonprofit laws, but there are significant discrepancies between proposals.25 Policymakers disagree on issues of liability and how to account for the lack of shareholders in the nonprofit sphere. There are broad concerns about assigning liability to the point of discouraging volunteerism. There are also questions on how to define and differentiate membership and stakeholders for a nonprofit. On whose behalf are nonprofit leaders acting? Are those who utilize or benefit from a nonprofit considered stakeholders?

Shareholders purportedly have power to guide the trajectory of the corporation by using their votes and organizing to hold managers accountable. Yet courts have used corporate law as a tool to weed out any semblance of social activism from shareholders attempting to take stakeholder interests into account.26 Similarly, on the nonprofit side, courts have limited the ability of certain member-groups from engaging at all.27 Corporate law also precludes stakeholders from holding business corporations accountable to their public statements of corporate social responsibility, dismissing these commitments as “mere corporate puffery.”{{See, Pub. Sch. Teachers Pension & Ret. Fund v. Ford Motor Co. (In re Ford Motor Co. Sec. Litig.), 381 F.3d 563 (6th Cir. 2004),

}}

Nonprofits, on the other hand, are beholden to many corporate law theories that prioritize profit-seeking activity and shareholder primacy, which naturally conflicts with the core aspects of nonprofits, most notably the lack of shareholders.

Directors, Boards, and Governance

“Directors of nonprofit organizations are called upon to perform several functions. Some directors give or raise funds; others provide special expertise; others maintain ties to an important community; others are there because their stature serves as a signal that the organization does good work. And some—perhaps just a few—govern.”28

Nonprofit board members are generally responsible for guiding the nonprofit by adopting ethical, legal, and financial policies that make sure the organization stays healthy.29 Boards also set executive compensation and fundraise on behalf of the organization.

Following the Enron scandal in 2002, Congress passed the Sarbanes-Oxley Act which was intended to strengthen business corporation governance practices and deter fraud in the private sector.30 Nonprofits adapted many of the provisions in the Act to update their governance procedures, such as creating conflict of interest policies, conducting regular auditing, updating financial and accounting systems, and implementing disclosure policies. This shift was influenced by the presence of corporate board members who served as a “vehicle through which developments practices in the corporate sector [were] imported into the nonprofit boardroom.”31

The increased professionalization of board governance created a pipeline that prioritized business experience, while ignoring other necessary board qualifications such as nonprofit work experience, social scholarship, or community representation.32 For example, nonprofit boards have consistently lacked racial and ethnic diversity.33 These private sector practices continue to influence the way nonprofit boards operate.

Liability

Fully incorporated nonprofits have similar limited liability protections that are afforded to business corporations.34 This protects directors and officers from being personally liable to any suits brought against the corporation. Nonprofit board members owe the organization a duty of loyalty and care, which requires them to act in the best interest of the nonprofit rather than their own interests.35

However, twenty-one state statues permit nonprofit corporations to adopt charter amendments shielding directors from liability for breaches of the duty of care.36 Because there is a view that directors are highly regarded members of the community and voluntarily spending hours of their time overseeing a charity, courts have been hesitant to raise the standard of the duty of care out of fear that “few sensible people would serve on the boards of nonprofit organizations.”37

This low level of risk can lead to poor oversight of nonprofits and remove standard incentives to manage the nonprofit effectively. It also makes it difficult for the nonprofit to hold board members accountable for mismanagement or breaches to their duty of care.

Funding and Donors

Philanthropic endeavors have a long history of prioritizing the desires of the donor, which historically included individuals who have occupied a position of privilege and received wealth from the success of their corporations. Today, large scale donors are now seen as legitimate players in public service, and their influence with nonprofits is considerable.38 In 2018, corporations gave $20.05 billion to charitable organizations in 2018.39 This accounts for less than 1% of revenue sources received by nonprofits.40 After fees collected for services, government grants and contracts account for the bulk of nonprofit revenue, distantly followed by individual giving. Corporate and foundation donating together are less than individual giving.

Figure 5: Revenue Sources for Nonprofits, 2016 (Source: IRS Business Master Files, and electronic (e-File) Form 990 returns processed for fiscal years ending circa 2016 (June 2018) by DataLake Nonprofit Research (datalake.net), Urban Institute’s National Center for Charitable Statistics).

And yet, nonprofits continue to view corporate partnerships and donations as a “win-win” situation, where “corporate sponsors receive positive publicity for their goodwill, [and] the nonprofit, in turn, not only receives financial or in-kind support from the corporation, but also receives increased public awareness and enhanced creditability,: 41

Researchers and activists have challenged the notion that corporate partnerships are truly a “win” for nonprofits, pointing to studies that show corporate sponsorships may actually decrease rates of individual donation.42 In addition, more people are critical of the ways large-scale donors may perpetuate injustice, recognizing that the things most donors care about “are the things least likely to change the systems of oppression and exploitation that make philanthropy necessary.”43

By championing corporate donations, nonprofits contribute to the narrative that corporate giving is too essential to shut out. In reality, individual donations, foundation giving, and government grants are healthy funding streams that align more easily with a nonprofit’s mission to address a social issue.

Speech and Political Organizing

“Many nonprofits prefer not to stray from their primary service-delivery programs, either for fear of losing their tax-exempt status or because of a desire to dedicate all of their resources directly to their constituencies. But if organizations want to effect permanent, systemic changes, they need to also be prepared to advocate . . . for their causes and constituencies.”44

Expansive scholarship exists on corporate speech and the political lobbying landscape following Citizens United, which granted business corporations expansive speech rights.45 In summation, business corporations today have legal cover to speak on all political issues that influence public discourse or to donate to candidates for public office. Nonprofits, however, are restricted from speaking on political issues, or do any substantial advocacy, without losing their tax exempt status. The law is unclear about what “substantial” advocacy is, but this vagueness makes advocacy activities more risky for 501(c)3 nonprofits.46

To push against the powerful speech rights of business corporations, some nonprofits have organized under the 501(c)4 designation to engage in more substantial political advocacy and endorse political candidates. And while 501(c)4 organizations are also tax-exempt, donations to 501(c)4 organizations are not tax deductible, the IRS saw a surge in 501(c)4 applications following Citizens United in 201047. However, most nonprofits remain 501(c)3 organizations and are unable to engage public policy arguments on the same level as business corporations.

A SHIFT IN THE PLAYING FIELD

Nonprofits today are competing with business corporations on multiple fronts, often hindered by the legal systems that allow businesses to act with impunity. However, some nonprofits and corporate executives have been taking a deeper look at the way they utilize their power and take stock of harms they may cause. Questions of accountability, utilizing social movements, and looking inward have risen in both arenas as the country further polarizes and pressure keeps building within the country.

Benefit Corporations

“Society’s most challenging problems cannot be solved by government and nonprofits alone. . .. By harnessing the power of business, B Corps use profits and growth as a means to a greater end: positive impact for their employees, communities, and the environment.” 48

Another recent development in corporate actors engaging in social change work is the creation of benefit corporations (B Corporations), which are “legally empowered to pursue positive stakeholder impact alongside profit.”49 By tying the success of their company with their impact on stakeholders, some benefit corporations can integrate third-party considerations into their profit-seeking decisions.50

The nonprofit B Lab drafted the Model Benefit Corporation Legislation (MCBL) in 2006, and has since seen 38 states adopt benefit corporation statutes.51 The certification process from B Lab requires an additional set of standards that must be met before being certified.

Figure 6: Examples of Benefit Corporations (Source: Unknown).

And yet, companies eligible for certification include for-profit higher education, companies involved in the prison industry, companies operating zoos, debt collection agencies, and fossil fuel companies.52 While B Lab claims to have high standards on who is granted certification, critics of benefit corporations question the ability of a business corporation to truly pursue social good while perpetuating social harms.

Nonprofit Activism

In the nonprofit space, some organizations maneuvering around these competitors by wielding their power in more effective ways.53 Some are creating advocacy arms created as 501(c)4 entities to more freely engage in political advocacy. Others are being more intentional about putting social pressure directly on business executives, rethinking their board compositions in terms of background and diversity, updating their language and philosophies more in line with broader social movements. While the underlying power differences are still present, these developments may show a shift in the way people view the role of business corporations and nonprofits.54

RIGHTING THE SCALES

Nonprofits have proven to be resilient and innovative in the face of increased competition and scrutiny. Yet, business corporations, empowered by corporate law, have created a system that actively hinders nonprofits while uplifting market-friendly solutions to major issues of injustice. There are four avenues through which to begin addressing this dynamic and unveiling the scope of the problem.

- Legal scholarship: Legal scholars and corporate law theorists must critically analyze corporate law’s role in nonprofit structures and meaningfully engage with the legal doctrine and rhetoric that conflicts with the reality and purpose of nonprofit corporations. Further, we must reflect on the way outdated charity rhetoric influences policy decisions and promotes unrealistic portrayals of nonprofits as they exist today.

- Organizational alignment: Nonprofits can pursue intersectional frameworks to create organizational structures that align with broader justice goals. This can begin by analyzing where money is coming from, how employees are provided for, who serves on boards, and how one’s work empowers various stakeholders.

- Corporate Restraint: Business corporations wield tremendous power to influence society, political systems, and the environment. In the absence of stricter legislation or a fundamental shift in the law, benefit corporations may offer a more desirable approach for business corporations to meaningfully take into account stakeholder interests.

- Government Action: Government regulation that promotes stakeholder liability for corporations, expands access to social services grants, and better regulates corporate law could promote a more balanced playing field between business corporations and nonprofits.

These proposals may not provide sweeping change or alter fundamental questions about corporate law, but their adoption could shift the power dynamic between nonprofits and business corporations and provide a more critical lens through which to analyze corporate law’s influence in nonprofits.

CONCLUSION

Nonprofits have provided critical services and structures that allow people to organize together to address social issues. And yet, nonprofits are bound by a corporate law structure that prioritizes profit-seeking businesses, which is an ill-fitting standard by which to govern nonprofit structures and assign liability. Business corporations engaged in a decades-long endeavor to position themselves as legitimate actors in justice movements, thereby encroaching on the domain that historically was occupied by nonprofits. Nonprofits now compete with business corporations to defend their legitimacy and vie for limited resources, sometimes acting contrary to their social missions.

While nonprofits have shown resiliency, too little analysis has been conducted to seriously challenge the systems at play that hinder nonprofits in their ability to compete with business encroachment in justice-oriented spaces. With further legal scholarship and a commitment to taking the offensive against corporate capture, nonprofits can push back against outside actors who use nonprofits as cover and subvert justice movements.

FURTHER READING

Books

Winners Take All: The Elite Charade of Changing the World by Anand Giridharadas.

The State of Nonprofit America by Lester Salamon.

Law Review Articles

Blount, Justin and Offessi-Danso, Kwabena, “The Benefit Corporation: A Questionable Solution to a Non-Existent Problem,” 44 St. Mary’s L. J. (2013).

Brody, Evelyn, “The Board of Nonprofit Organizations: Puzzling Through the Gaps Between Law and Practice,” 76 Fordham L. Rev. (2007).

Haber, Michael, “The New Activist Non-Profits: Four Models Breaking from the Non-Profit Industrial Complex,” 73 U. Miami L. Rev. 863 (2019).

Hansmann, Henry B., “Reforming Nonprofit Corporation Law,” 129 U. Penn. L. Rev. 3, 501 (1981).

Reports

Francie Ostrower, “Nonprofit Governance in the United States: Findings on Performance and Accountability from the First National Representative Study,” The Urban Institute, Center on Nonprofits and Philanthropy, 2007.

Arnsberger, Paul et. al, “A History of the Tax-Exempt Sector,” Statistics of Income Bulletin, Internal Revenue Service (2008).

Forti, Matthew, “Challenging Conventional Wisdom on Nonprofit Boards,” Stanford Social Innovation Review (2018).

Appendix A

Appendix A: Additional Material, Organizational Reference Chart, February 2021 (Source: Internal Revenue Service, Publication 557, https://www.irs.gov/publications/p557#en_US_202102_publink10002273).

Appendix B

Appendix B: Nonprofit Chief Executive Demographics, 2017 (Source: Board Source, Leading with Intent, 2017).