PART 1: INTRODUCTION

Simon and his cellmate, Tina are incarcerated at a privately owned and operated Arizona prison.1 Separately, they seek assistance from a nonprofit that works with incarcerated people who are sexually abused in custody.

Simon was sexually abused by an older, larger, inmate when he was in a general population housing unit, where residents2 are housed in triple-tier bunk beds, dozens to a room, with a low ratio of guards to residents. Out of desperation, Simon intentionally fought an officer in order to be transferred to segregated housing (where he would be restricted to a cell designed for one person but housing two).

Tina, Simon’s cellmate, was in segregated housing due to her status as a trans woman. The medical staff had refused to provide her hormone therapy, then had provided a dosage that required Tina to endure what she described as “the painful process of repeatedly going through puberty.” When Tina reported medical neglect to an officer who began sexually abusing her; Tina submitted to his abuse for fear that without his medical “advocacy,” her treatment would terminate again.

The nonprofit advocacy group both detainees contact cannot locate an oversight body within the prison corporation. Subsequently, the nonprofit could not locate Simon or Tina.

What do these tragic stories have to do with corporate law?

Corporate law creates and insulates corporate power, and corporate power significantly contributes to decreased transparency and accountability among privatized detention facilities. In this paper, I examine the dispositionist and legitimizing narratives that facilitate the prison industrial complex and the myriad harms it causes, and I challenge fundamental tenets of, and cover provided by, corporate law, especially in the context of U.S. correctional privatization today; highlight the relationship between corrections privatization and the absence of provider accountability and transparency; and offer suggestions for reframing corporate prison industrial complex narratives in order ultimately to dismantle this destructive industry.

Private investment in the prison industrial complex3 and the growth of mass incarceration have been symbiotic for decades. While government regulation of prisons and jails unquestionably has its limitations, the shift from regulation to markets has often constituted a shift from public visibility and accountability to private invisibility and unaccountability.

This lack of transparency and accountability can manifest in several ways, including increased violence; mismanagement of corrections staff; opaque or nonexistent grievance processes; lack of medical and mental health care data; inadequate or nonexistent platforms for locating incarcerated individuals; inconsistent or nonexistent death records; lower rates of early release and higher rates of recidivism, due to private prison corporations’ profit motive to keep their facilities full; and even lobbying efforts to create stricter laws with longer sentences.

Government claims of pursuing the public interest (primarily through being “tough on crime” and “cost-efficiency”) within the prison privatization context have normalized and legitimated the violence of displacement and caging, while macro scripts of civil and criminal law have obscured the root causes of poverty and crime through a dominant narrative of “order maintenance.” Abolition of private correctional corporate contracts is the only solution.

PART 2: (RE)FRAMING CORPORATE LAW: DOMINANT NARRATIVES, SYSTEM JUSTIFICATION, DISPOSITIONISM, “STICK” AND “BALL”

Legitimacy

Tom R. Tyler’s proposition that procedures beget legitimation permeates corporate law, in general, and the private prison industry, in particular.4 Corporate law leads the public to rely on corporate governance without any basis for assuming that the law or governance policies and procedures actually rein in corporate power; instead, corporate law is often evidence of the deep capture of corporate legitimation, insofar as it enables and legitimates corporate power.

As the view that corporations are per se legitimate persists, corporations enjoy substantial liberty to shape and select the rules with which they comply (and in the instant case, those that apply to court-involved individuals who populate private prisons). The more rules there are, and the “stricter” those rules seem to be, the more legitimate the system and its proponents appear to the general public, and the fact that corporations may have co-opted the administrations and agencies that are supposed to regulate them goes largely unnoticed absent serious scandal (e.g., courts claim to lack expertise on corporate decision-making; companies market themselves as having an interest in both the public welfare and regulation). Corporations have a presumption of legitimacy; however, the claim to procedural fairness that rationalizes the dispositionist story upon which mass incarceration and prison privatization are constructed is an illusion.

Agency Theory

Agency theory in corporate law developed to describe corporate relationships in which one person (the agent) is acting on behalf of another person (the principal), subject to the principal’s control, and both the agent and principal have consented to this dynamic. This theory evolved to support the assertion that good management could facilitate the alignment of divergent interests.5

Agency theory provides a lens for examining prison legitimacy and oversight.6 Government entities leverage terms like “monitoring,” “contracts,” and “oversight” to suggest that they have the power to protect non-governmental entities from pursuing interests that would be detrimental to the public. For example, if principals and agents have different values, but “monitoring” can control for that possibility. Citizens rely on government to prevent wrongdoing by private contractors;7 however, if the government does not sufficiently monitor its (private prison) contractors, this lack of transparency results in information asymmetry and lack of accountability.8

Prisons are built on a dispositionist story that depends on and justifies the disappearance of a large population behind bars, but this disappearance facilitates freedom from transparency and lack of accountability for cost-cutting, profit-maximizing measures.

System Justification, Dispositionism, and Situationism

Corporate legal theory and scholarship have historically championed a rational choice framework for analyzing corporate law, compliance and regulation. Scholars have criticized the rational choice framework through a behavioral economics lens. System justification theory (“SJT”) posits “that decision making is embedded in psychological attachments to systems.”9

Critical realists have coined the term “fundamental attribution error”10 to describe the phenomenon that “people tend to ascribe the vast majority of human behavior to disposition-based choice, despite the fact that our actions are more a reflection of situation—unseen or underappreciated features in our environment and within our interiors;” however, they also question “how dispositionism maintains its dominance despite the fact that it misses so much of what actually moves us.”11 These schema inform our criminal legal system. Dispositionist thinking allows us to believe that our high incarceration rates are justified because the people housed in detention facilities deserve to be separated from the general public and punished for their behavior. This rationale supports corporations ensuring public safety by operating correctional facilities. Dispositionism might even lead to a conclusion that incarcerated people deserve corporate impositions like high-cost telecommunication with loved ones.12 Scholars Adam Benforado and Jon Hanson note that, within our society, “…there are some institutions and interests that have both a particularly strong stake in promoting dispositionism…the most vital of these entities are commercial interests—particularly large, profit-oriented corporations—that rely on a firmly engrained dispositionism to ensure their continued ability to manipulate members of the public to maximize profit while escaping liability and regulation…those interests will be most active in framing policy issues in ways that advance—and protect—dispositionism.”13

Certainly scandals arise in the privatized correctional sphere—and some scandals have received significant publicity—but the corporations behind these scandals still exist today; meanwhile, people have relatives and partners in custody. How does this happen? Benforado and Hanson explain that “[s]ituationist explanations threaten conceptions of our ingroups and ourselves….Situationist attributions of prisoner mistreatment are generally disfavored because they stand as a threat to our positive conceptions of ourselves and the groups with which we identify; they suggest that we may, in some sense, be culpable for abuse.” The authors cite psychologist Philip Zimbardo’s observation: “[W]e want to believe we are good, we are different, we are better” and elaborate that “[a] dispositionist conception of sound, well-reasoned policies implemented incorrectly by a few sadist prison guards against individuals who, in any case, deserved to be mistreated helps us maintain our reassuring sense that ‘we are good.’”14

Such narratives, like those described above, play a significant role in how we perceive the world around us as just or unjust. The law participates in that process: it needs to legitimize its outcomes to justify its credibility and relevance in society. One of the fundamental questions in the law is “what is the cause of human behavior?”15 Two main answers typically surface, which can be described as a “stick” and a “ball.”16 “Stick” can be viewed as a person (whether an individual or corporate entity) who is moved by stable preferences; conversely, “ball” is an individual or entity moved by forces other than stable preferences. This distinction is critical: judges punish people who violated our society’s laws in some manner (“sticks”), and lawyers argue that these same people are, instead, “balls.”

Enterprise Liability

Enterprise liability doctrine exemplifies one way in which corporate law protects individuals as “balls” even if it holds a corporate entity or enterprise accountable as “stick.” Courts sometimes employ this doctrine to pool business assets of multiple corporations under the same ownership, disregarding their “separateness,” to satisfy the enterprise’s liabilities; however, the individual owners’ or managers’ assets remain protected. In Walkovsky v. Carlton, Carlton was the controlling shareholder for ten wholly-owned taxi corporations (a structure utilized to avoid high-cost liability insurance). When one of the cabs injured Walkovsky, he sued the individual cab driver, the nine other subsidiary corporations, and the owner of the parent corporation. The court accepted the enterprise liability charge, reasoning that Carlton held his ten artificially separated corporations out to the public as a single enterprise, but it refused also to hold Carlton personally liable.17 Thus, the law viewed Carlton as a “ball,” whose corporations simply ran into hard times with this accident, and even inferred that the legislature was responsible for addressing this taxi-cab-industry avoidance of costly insurance.

Although Carlton might seem a sympathetic figure, SJT suggests that system justification may lead to unwarranted protection in such circumstances; this in turn illustrates why a foundational corporate law concept, the Business Judgment Rule (the “BJR”), is problematic.

Duty of Care & Duty of Loyalty

In corporate law, directors have two primary obligations: duty of care and duty of loyalty; however, these duties are absent from Delaware General Corporation Law (“DGCL”) and the Model Business Corporation Act (“MBCA”); instead, the duties stem from cases and commentaries. Essentially, courts use the BJR as a doctrine of abstention18 to limit their jurisdiction over substantive board decisions.19

In most cases, directors must behave egregiously for a court to make an exception to the BJR.20 Smith v. Van Gorkam appeared to be a groundbreaking case in holding directors accountable for breaching their duty of care by gross negligence in failing to remain sufficiently informed, but the case’s impact was short-lived. The Delaware legislature passed section 102(b)(7) shortly thereafter, and the MBCA followed suit: thus, even if directors are grossly negligent in failing to become sufficiently informed regarding a pending decision, they can still escape liability if covered by a Delaware corporation whose certificate of incorporation that eliminated that duty or are in an MBCA state, where the corporation’s articles essentially eliminate the duty of care.21

The “duty of loyalty” (to shareholders on the part of directors) also does little to limit managers’ discretion regarding whose interests they serve and can become a shield for managers who act of their own accord. And even when managers allude to shareholder interests, this “duty” can be harmful to other constituencies. In U.S. Workers v. U.S. Steel Corp., (1980), for example, the corporation intended to close mills in Youngstown, OH, due to lacking profits. Before doing so, the corporation encouraged workers to endeavor to increase mill profits to prevent closures. The workers followed this directive, but profits still failed to increase. Two workers unions, a Congressman, and the Ohio Attorney General filed lawsuits. On appeal, the court acknowledged the workers’ efforts but it declined to rule in favor of the workers, designating the issue a legislative one.22 The company described itself in “ball” terms (subject to the market, regulations, etc.) and the workers as “sticks” (they chose not to invest and modernize).23 The court’s ruling accepted the “ball” characterization; thus, in practice, U.S. Steel demonstrates that shareholder primacy can allow managers discretion to ignore other constituencies and gives them license to manipulate and exploit other constituencies in the name of pursuing shareholder interests.24

Tying these concepts to correctional corporations, such companies justify their extreme measures, and lack of accountability therefor, in “ball” terms, claiming that criminals are difficult to control, and detention facilities are like war zones—you have to do everything you can to maintain control and survive. This is especially effective when the facilities are overcrowded and understaffed (often intentionally).

PART 3: U.S. PRISON PRIVATIZATION

Overview

Despite reform and abolition efforts nationwide, including some bipartisan efforts to address mass incarceration, the United States continues to maintain the highest rate of incarceration in the world. According to the 2020 version of the Prison Policy Initiative’s annual assessment, “[t]he American criminal justice system holds almost 2.3 million people in 1,833 state prisons, 110 federal prisons, 1,772 juvenile correctional facilities, 3,134 local jails, 218 immigration detention facilities, and 80 Indian Country jails as well as in military prisons, civil commitment centers, state psychiatric hospitals, and prisons in the U.S. territories.”25

And, according to a 2021 report by The Sentencing Project, “[p]rivate prisons in the U.S. incarcerated 115,428 people in 2019, representing 8% of the total state and federal prison population. Since 2000, the number of people housed in private prisons has increased 32% compared to an overall rise in the prison population of 3%.”26 When mass incarceration resulting from the “War on Drugs” soared throughout the 1970s and 1980s, the demand for prison space became so substantial that the private sector identified incarceration as a promising area of opportunity. Consequently, Corrections Corporation of America (“CCA”), the first major private prison corporation, emerged in 1983.27

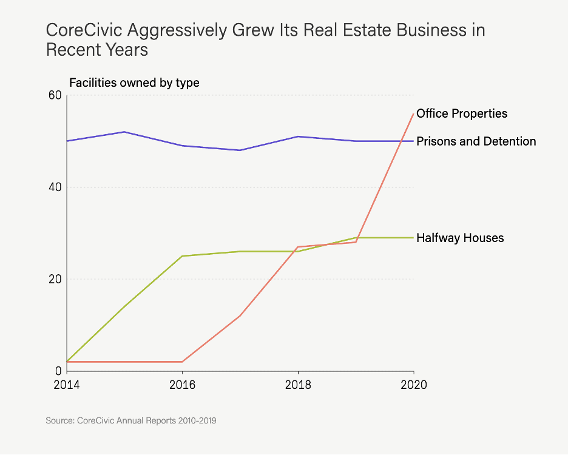

Today, there are three main private prison corporations: CCA, which rebranded as CoreCivic in 2016, The GEO Group (“GEO”), and The Management & Training Corporation (“MTC”). The top private prison companies make collective revenues upwards of $3 billion per year. Like corporations in other industries, these companies help fund elections to ensure that they will have influence on legislative decisions that affect them, e.g., that their facilities will continue to receive a significant influx of inmates.28

Thus, when the Reagan Administration’s policies on mental health and welfare drove people into prisons, these prisoners became invisible, removed from important U.S. calculations of wages, employment figures, and for funding allocations; consequently, the results of such legitimized assessments became distorted. Moreover, increasing barriers to voting eliminates the political voice of the formerly-incarcerated population, making it nearly impossible for them to take action that might address prison privatization and related issues that formerly-incarcerated people experience.

Finances

A 2016 report found that six banks were especially significant financers of CCA’s and GEO’s debt.29 The banks benefit by collecting interest, bond, credit, and loan fees; they also invest clients in the companies’ shares and own shares themselves. These relationships have helped both companies grow.

Political Influence

Private prison corporations are empowered to wield their political influence and capital to ensure continued profit. For example, GEO profited substantially under President Trump; this was unsurprising given its significant donations to his campaign, which led to a Federal Election Commission (“FEC”) complaint that GEO violated a federal ban on government contractors’ campaign donations.30 The complaining watchdog group emphasized that the ban “…protects against a…system in which wealthy special interests are rewarded for their political contributions with lucrative government contracts. This, [prevents] the…appearance that taxpayer-funded contracts are for sale.”31 Except when it doesn’t.

GEO responded to the complaint by relying on classic corporate law, evoking Walkovsky concepts: “Although GEO Corrections Holdings Inc., the company that made the donation, is a wholly-owned subsidiary of the GEO Group, it is a non-contracting legal entity and has no contracts with any governmental agency.”32 The watchdog group countered that the two entities are inseparable: the subsidiary’s first contribution33 correlated with the Department of Justice (“DOJ”) recommendation to end federal prison privatization because it found that privatization demonstrably does not cost less and consistently presents major safety concerns for government-operated prisons.34 While GEO’s stock value plummeted following this DOJ declaration, it neared its peak value during Trump’s early days in office: his campaign platform appealed to the private corrections industry, and GEO seized the opportunity.

A case like this problematizes the limits of Citizens United, which does not explicitly address government-contracting companies.35 The FEC has upheld similar contractors’ contributions but has imposed sanctions on others; enforcement is inconsistent and administration-dependent.

Lack of Access to Information

Private agencies providing correctional services rely on claims about capacity and confidentiality to ensure maximization of profits from each detainee and unavailability of information. Moreover, unlike governments and notwithstanding their government contracts, private institutions are not automatically36 subject to the Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”), open-records statutes, and the Administrative Procedures Act.37

While FOIA requests are not necessarily an ideal means of holding institutions accountable, the lack of information or transparency certainly enables corruption. Corrections oversight expert, Michele Deitch, emphasizes that the closed environment of correctional facilities exacerbates the probability of corruption and maladministration.38

PART 5: POTENTIAL SOLUTIONS AND THEIR RELATIONSHIP TO THE CORPORATE LAW PROBLEM

Corporate law enables companies, their employees, and investors to profit off of people stripped of their liberty and, in many cases, denied sufficient care, safety, nutrition, wages, representation, and communication. Moreover, their existence out of custody, whether through “rehabilitation,” EM, or otherwise is defined by barriers that harm their entire communities. Finally, these corporations obscure violence, trauma, addiction, and deaths, sometimes without taking any corrective measures internally.50 A humane approach to public safety concerns requires the abolition of incarceration. The best interim solution is truly independent correctional oversight and an end to the entire correctional privatization industry.

There are additional methods for fighting this corporate correctional assault on humanity. For example, Worth Rises offers a “curriculum”51 through which the general public can learn about the prison industrial complex and steps they can take, financially and otherwise, towards abolishing it. Another organization, called As You Sow, has created an investment analysis tool to assist users with screening their investments for private corrections affiliations.

While the concepts of Corporate Social Responsibility (“CSR”) and Environmental, Social, and Corporate Governance (“ESG”) are imperfect, they nonetheless offer lessons in how to inform, inspire, and evaluate corporate and/or investor actions and regulatory responses to pervasive injustice. RFP processes can also offer lessons about where contracting and outsourcing go wrong, as well as the indicators of corruption. Litigation is a powerful tool and can result in court-appointed monitoring. Prison law and policy experts can be especially effective monitors. Finally, abolitionist proposals can provide checkpoints, inspiration, and vision throughout what could be an arduous dismantling process.

PART 6: CONCLUSIONS

Corporate law and corporate power insulate private prison owners, operators, and contractors from essential monitoring, oversight, and accountability. The macro scripts that have legitimated the alliance between “private” and “public” actors within the criminal law and carceral sector demonstrate the myriad ways in which these scripts and system justifications disintegrate when subjected to private and public exposure of what really happens inside private detention. Claims of pursuing the public interest (primarily through “tough on crime” approaches and “cost-efficient” outsourcing) within the prison privatization context have normalized and legitimated the violence of displacement and caging, while legitimizing macro scripts have obscured the root causes of poverty and crime through a dominant narrative, supported politically, of “order maintenance.”

The lack of transparency and accountability enjoyed by private corrections providers is also consistent with troubling examples outside of the carceral state. Absent, or until, prison abolition, a humane approach to violence and crime prevention will require the urgent and permanent termination of all private correctional contracts, and greater transparency and accountability in the interim.