Rough Transcript, Critical Legal Theory Podcast, Episode 5

Duncan Kennedy [00:00:07] [00:00:07] The Harvard Law School classroom, this Socratically organized classroom generated a very, very powerful hierarchy among students. So there were the gunners, there were the masses, and there were the back benchers. A basic goal of teaching for me was to try to crack this structure. [18.9s]

Jon Hanson [00:00:29] Welcome to Episode Five of the Critical Legal Theory Podcast, an oral history podcast where we hear from legal theorists and practitioners about the ideas that shaped their critical approach to legal theory and law. I’m Jon Hanson, the Alan A. Stone Professor of Law and Director of the Systemic Justice Project at Harvard Law School.

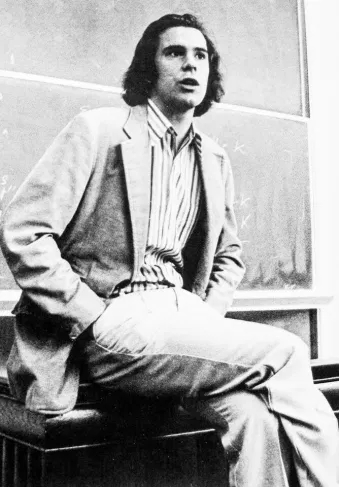

This episode is the second part of Abbey Marr’s three-part interview of Duncan Kennedy. In this portion of their discussion, Duncan focuses on questions of hierarchy. How could a movement built on the idea of criticizing illegitimate hierarchy structure itself? Should CLS conferences have official leaders? And do those positions or less visible structures have the effect of enacting illegitimate hierarchy like patriarchy and white supremacy? Kennedy also discusses CLS critiques of hierarchy within what he calls the profoundly conservatizing law school classroom. He describes his efforts to address some of the harmful tendencies of the Socratic method and how he disarmed the so-called gunners by adopting the no-hassle pass and other pedagogical techniques. This portion of the interview begins to explore the complex, intersectional tensions along vectors of race and gender, and the growing fractures that would contribute to the sudden and complete burnout of CLS as a movement in the early 1990s.

Throughout this episode, you’ll hear Duncan refer to people, events, and scholarly works that impacted or interacted with CLS. You can find more information about those topics in the links in the show notes on our website at systemicjustice.org.

Abbey Marr [00:02:24] Fascinating. And it begins to touch on how you work to break down hierarchy inside the CLS movement. I was wondering if you could touch on other ways you tried to or debated how to address these internal hierarchies.

Duncan Kennedy [00:02:35] Okay, let’s do it this way. So there are two different anti hierarchy programs, the anti-hierarchal program in law schools. That’s the overt programmatic contention, number one. So it’s not. So the idea is to oppose various aspects of the way law schools are organized on the grounds that they are illegitimately hierarchical. And I hope you’re going to ask me about that so we can talk about what is the content of such a program. The second thing is the issue which in the old left was called the prefiguration issue; prefiguration, it was the idea that the movement should prefigure the society to which it aspires. So that would be the idea of if you are an anti hierarchy movement, you have a target. So people often just forget the importance of the distinction. There’s a target. Going after the target, you don’t have to be unhierarchical to go after the target. You can go after capitalism with a rigidly hierarchical Communist Party that understands itself to be virtually a military, virtually military in its discipline, although the goal is communism, a totally egalitarian society. Right? So there’s no connection necessary. The prefigurative idea is a new left idea. So the new left idea, a very explicit . . . — SDS is probably one of the main sources of it — the idea is the movement itself should embody the ideals that it is trying to fight for in the larger society. So you’ve asked me first about the movement. We could have started first with law schools. What’s wrong with law schools? But starting with the movement. Here would be some examples. Let’s see. I mean, I’ll probably have to add to the list. So the first thing would be the organization should not have a formal hierarchy. Now, these things are always relative. And over the course of CLS, people would say, “no, we have to have an executive committee that functions” we need . . . And so there were the organization people and the anti-organization people. And the way this works in real life, the anti-organizational people, I was an anti-organization person, and the organization people would always say, “of course you’re an anti organizational person. As long as there’s no organization, you’re in power, Duncan, because of your network.” To which I would say “no, the opposite is the case. Just look at what’s happened as a result of the absence of organization. Look at these people who have flowed in and flowed out and all the bad things that haven’t happened that have happened over there, blah, blah, blah.” So that was a first thing, formal organization versus no formal organization. A second thing was the organization of the conferences. This is very, very important. So there are like ten conferences. A guy or a woman gets put in charge of the conference at his school, might be two people doing it together, and they are totally in charge of it. So the center has no control, but consultation is everywhere, so that means that the person is teaching . . . the third conference was at Camden. [00:05:28]Rand Rosenblatt, [0.8s] who was one of the Yale people and his wife [00:05:31]Ann Freedman, they [0.2s] organized the whole thing. They would have said they had no power in the CLS network, whatever, except what they exercised through organizing this conference. So they weren’t part of the core. And the people who organized the conferences were sometimes core people, but very often they became core people through the organizing of the conference.

So the basic idea is you don’t . . . it’s not boot camp. You start out basically as an autonomous tenure person, and you do that . . . At the conferences, there were almost no speakers, and everybody invited was asked to give a paper. So the basic principle of the conference was not there are presenters and audience. This is a much more common model today. In fact, there was no . . . the idea was anybody could give a paper and the background initial presumption was everybody would give a paper. Now, this was also influenced by the fact that to get money from your school to go to a conference, you had to tell the dean you were going to give a paper. So these two things corresponded. So they allowed an enormous number of people to come for free because at a CLS conference there would be 50 or 60 people would give papers. That was very in the context of the time, an egalitarian kind of a move. Major speakers . . . again there would be a struggle. So “we have to have any? How about plenaries? Plenaries are bad. Plenaries are really, really bad. So let’s have an absolute minimum.” Other people would say “plenaries are crucial because you won’t have . . . you can’t combat hierarchy unless you convey the scene so that people who are out of it can get a sense of it. And with your 50, 50 or 60 papers in 20 different panels, you’ve created something that’s unintelligible. We need to make it intelligible.” So that would be an argument where the hierarchy arguments go back and forth. So, right, you get it. There’s no simple answer to this down at the micro level.

Abbey Marr [00:07:24] And how did this play out with students?

Duncan Kennedy [00:07:27] Students. So this was really, really unusual. So we invited and recruited sometimes 100 or 200 students to come to a CLS conference. So the idea was the CLS conference was totally open to students and at least three had two or three, maybe four of them had two or three hundred. Problem for Mark: so they all sign up and we have a mailing list. Can’t really tell millions . . . It’s 200 names. They’re never going to pay dues and they will never appear again, except five of them who will become professors and will be part of the network five years later. So it’s not effective. There are 200 people there and the pay off of five would be great in terms of the organizing projects and law schools. So those are some examples.

Abbey Marr [00:08:10] Fascinating. You touched on it slightly, but can you talk further about fighting hierarchy inside legal education more generally?

Duncan Kennedy [00:08:17] From the very beginning, there were some highly symbolic issues for critical legal studies, of which the most important was the particular use of the Socratic method as a kind of powerful disciplinary mechanism. And that’s emblematic of the teacher-student hierarchy attacked by critical legal studies. The most dramatic incident is the [00:08:38]no-hassle pass thing written up in this article by Dan Bahar [2.9s] or the paper by Dan Bahar describing the massive faculty, Harvard Law School faculty, debate about whether there should be a no-hassle pass. But another very significant dimension, which has to do with also with CLS, is the relation between teachers and students. So the there the basic idea was that the people . . . teachers associated with CLS tended at Harvard — to some extent, but not, you know, it’s variable — to have the idea that student-teacher political collaboration could cross a very well-established conventional line as to how involved with a student activity faculty members should be symbolized by what happens when the students are sitting in the dean’s office on the issue of hiring a Black woman professor. And there are many different ranges. None of us ever actually went and sat in with the students, but we did a million things like that. And I was often actually involved to one degree or another with the organization of things like that. And to the extent my colleagues were aware of it, they considered it to be a flagrant violation of the very basic norms of the institution. And I really they really didn’t like it and I completely understand it. I understand they hated it. It just struck them as terrible. But these are less interesting than the issue of student hierarchy among the students. So from my point of view, the most important hierarchy issue for me that I found most interesting as a teacher was hierarchy in the classroom. So, and now everything is ambivalent. So here the most basic question was the Harvard Law School classroom. [00:10:21]This Socratically organized classroom generated a very, very powerful hierarchy among students. So there were the gunners, there were the masses, and there were the backbenchers, [11.8s] you know, and a backbencher, I don’t think is any longer a phrase. Do you still talk about gunners or.

Abbey Marr [00:10:40] Yes, a lot.

Duncan Kennedy [00:10:41] So gunners, masses, and backbenchers, and they were really, really different. The students in these categories had completely different experiences of law school. The gunners were there were more gunners . . . sorry, there were more backbenchers than sat in the backbenches. There was a significant subcategory of students who really didn’t get it, really didn’t get it, they really had trouble understanding, and they just limped through, and they turned it into a black-letter exercise. And their belief was that you studied with study aides and you just got enough black literature in the exam. They never fully grasp what an issue spotter is, and that was desirable for the professors because you’re supposed to grade on a curve. We needed students who didn’t get it or we couldn’t grade, and we taught in such a way that significant numbers of students didn’t get it and we didn’t flunk them out. We just, you know, gave them bad grades. The gunners had an experience that was amazingly complex in which they both were the object of unbelievable revulsion, loathing from their fellow students, but also they were . . . the professors loved them. They were the allies of the professors. They were . . . Morty called them the feudal barons. [00:11:48]So there were the king and the barons, and a basic goal of teaching for me, was to try to crack this structure, to try to actually, as much as possible, prevent it. [11.2s] It was facilitated by liberalism and by conservative reaction both. So the the reactionaries did it by classroom techniques that altered . . . that were based on the idea of questions hard enough so only a very small number of students could answer them correctly. And easy questions done by the method of . . . you asked the question, you pointed to students code calling and student . . . . I don’t think this is almost ever done anymore, but it was very characteristic. . . “Megan, Joe. James,” . . “Yes.” So then one student is validated, the answers are short and that that’s the mass experience. The gunner’s experience is a volunteer for a very hard question, and backbenchers’ experience is horrifying because they are disciplined, so they are put on the spot. So the person is most likely to be put on the spot is an incompetent student. This is a sick system. The liberals sucked. So the liberals answer was, “This is horrible, it’s cruel, just let anybody talk.” And then they would have the experience that only the gunners talked. The gunners identified in other classes would be the only people who would talk. So this teacher is a deeply caring man or woman who basically wants everybody to participate and hate the Socratic method, would never ask a Socratic question, as questions would be a long silence, and then a gunner will answer the question. Why a long silence? Because everyone knows, gunners are hated and answering in these classrooms at Harvard Law School, talking in class was bad. It is bad to talk in class. Now the relation to the gunner . . . do you know what projective identification is, the psychological term? It is unbelievable antipathy to another person based on the fact that they are doing something that you would like to do but are not doing. So it’s very, very simple. So projective identification is the Harvard Law School class; the masses basically arrive and they’re totally committed to their own smartness. They got the best grades ever. They’re the best place in the world and they would like . . . the whole experience is teachers love them their whole lives. They’ve been teacher’s pets and here they are, everybody . . . Instantly, it is understood by most people that this system, it can’t go on. You know, we’re all here in the same room. The gunners theory is you’re wrong. It is the same. I am the one. So the gunner attitude, then, is just what everyone understands would destroy . . . Humanity would be reduced to a Hobbesian, short, brutish life. if everybody is . . . . And they’re violating this norm. The hatred of the gunners then is reflected on everybody else. So if I raise my hand, I’m a gunner. I recognize my loathing of the gunners. I know how much I hate them. If I raise my hand, I will then be subjected to that feeling that I myself feel towards the Gunners. Backbenchers basically know that the only way they’re going to be put . . . they know they can’t do it. So obviously they can’t participate because they don’t understand what’s going on. And there are a lot of students in this 1975 class who just didn’t understand what was going on. The most famous, most popular teachers taught many students who never got what they were trying to convey.

Abbey Marr [00:15:22] And what was your solution? How did you deal with that?

Duncan Kennedy [00:15:25] So it’s really a problem how to deal with it. So first thing is all cold calling, virtually no volunteering. Okay, Gunners. . . . And you would see them . . . be going like this and just stare off in the other direction. It was really fun. I mean, it was a hierarchical. This is exerting the power of the future is really, really changing the experience of the gunners. So I just didn’t call in gunners. And I was. Believe me, it wasn’t hard to figure out who the gunners were, so I just didn’t call on them. I only called on people who were not gunners. That was one technique. The second technique which I really liked, which I still use the course I’m teaching right now, is going down the row. So with a no-hassle pass, the no-hassle pass was crucial. Very elaborately stated, “when you’re called on, I’m going to cold calling people constantly all the time. When you’re called on, if you know your mind wandered, please pass. If you actually need to pee, just get up and go pee. I mean, don’t. I mean, this is totally no hassle; I really, really mean it.” And I did eventually convince people. So then I said it’s no-hassle pass and I’m just going to go down the row from here all the way down the row. “I’ve just asked a question. If you want to answer it, great, if not, pass.” Eight people would pass. And then a person who had never spoken before would speak. A person who had never spoken before would be the ninth person, because now it’s really seems low risk. Everybody else has punted, so. “Well, maybe it could be something like this. Professor Kennedy. What?” “Yesssss!, you win the brass ring.” So that was . . . So these are . . . Then another one would be small groups. So now with the people around you, in a group of no more than five, you have 4 minutes to answer this question. So nobody did that. That was a completely seven … late seventies, early eighties technique. So these are all techniques that were designed to deal with student hierarchy.

Abbey Marr [00:17:24] That’s really interesting to me, because it does seem like those same hierarchies bleed outside of the classroom as well. How did you see mentorships or student teacher relationships change as you change the classroom dynamics?

Duncan Kennedy [00:17:36] Remember, the movement is about law professors. So in this context, some students get into our stuff and they then approach us. An anti-hierarchical thing is that the ideal of the Harvard law professor of the time is you want to be approached by the people in the Law Review. We had a profound anti-Law Review bias, partly because they tended not to like us. So it wasn’t . . . it was mutual. They didn’t like us and we didn’t like them. So a very basic dynamic of CLS forming the national movement was the student who approaches you is a student who liked what’s going on in the class and then takes Roberto’s class or takes Morty’s class and then takes my class. So this student is identifying himself or herself as someone interested in our stuff, and we are willing to mentor irregardless of the status of the student, even if they have bad grades, let alone not being on the Law Review. So that’s a first thing. So very few of the crit professors, very, very few, if any. I mean, I’m not sure that a single crit professor who came from Harvard Law School in this period was on the Law Review. Two of them had the glory — not two but three of them, not two, but three — of the early, early people had the glory of turning it . . . making it out grades and turning it down. There was a gesture, totally narcissisticly gratifying, right. So “I could have it if I wanted to, but I don’t like your loathsome institution. I’d rather pursue my left wing academic interests and aspirations.” All three of them. So those are three different people, but that’s just three out of 25 who didn’t make the Law. Review and were almost always very . . . on some level it was humiliating. So they were going to become professors. Not making the Law Review; the Law Review was totally destructive institution in the life of the school.

Abbey Marr [00:19:36] Sounds familiar. So in terms of those people who then sought you out and the relationships you built, you talked about it being a norm at the time. And I feel that it’s still a norm that the sort of political relationship to the relationships between professors and students was a touchy one for professors. I was wondering if you could talk about that.

Duncan Kennedy [00:19:54] Well, it’s not exactly the question . . . The point was just to do something. So, for example, in the no-hassle pass thing, Richard Parker and I, who made this formal proposal to the faculty, we tried to get students to support it. In the pass-fail thing, student organizations favoring Pass Fail worked with us to try to bring it about. [00:20:20]So we were overtly allied with the student organization that was trying to get pass fail in the first year. It wasn’t that complicated. I mean, basically you shouldn’t meet in your office with a bunch of students to strategize how to get a pass-fail resolution through the faculty. And you shouldn’t lend your name as a faculty member to an organizing effort by students where they’re leafleting in the student boxes, saying, Join Professor Horowitz tonight to discuss the grading system where he’s going to denounce the grading system. So [30.7s] relatively straightforward. A very important other aspect of it, though, is that this is the Harvard scene, which was a very powerful faculty and student scene, was powerfully influenced by the student organizations that were progressive, and they were both student organizations like the National Lawyers Guild. And the national system was quite significant at one time. It grew . . . and it’s nothing now going up and down over time. The Labor law . . . the students interested in labor law, but then there were the clinical students and the Bureau students. So these were groups of left students. And then there were the students on the . . . there was the Unbound was the sort of last event that didn’t happen till CLS was over. Unbound is after CLS, but it was a last attempt . . . to get the students on. For example, CRCL were likely to be sympathetic to the students doing clinical and the students at the Bureau and the students in the Labor Law Project. So you got a certain . . . BLSA . . . there was a third-world coalition briefly, but general identity politics at Harvard were conservative, not progressive, with some very important exceptions, which had giant ramifications for critical race theory. Critical race theory had as part of its origin in a set of events at Harvard at the height of this period, which was the organization of a boycott of a course taught by Jack Greenberg — who was a very important head of the NAACP, crucial litigator, civil rights lawyer, white, Jewish Columbia professor — on the grounds that they wanted a Black person to teach this course. Totally outrageous; really serious beginning of CRT. And then some members of the faculty supported like two members of the faculty actually supported them, even though Jack Greenberg was the bosom buddy and the closest friend of people like Jim Vorenberg, who were serious pro-civil rights, deeply committed to racial equality. And they really thought this was the end. Black nationalism went out with the Panthers and here it’s come back in 1984 or something like that. Horror! S=so that’s the kind of thing we’re talking about.

Abbey Marr [00:23:07] Okay. I wanted to move on a little bit to the role of relationships and sort of mentor mentee now that we’re talking about students and how you built those mentor mentee relationships and how tensions started to rise. And whether you felt that that strengthened the movement in dealing with these tensions or sort of hurt the movement.

Duncan Kennedy [00:23:25] Well, so the. This is really it’s a story. So it starts out it’s these generationally coherent, white, middle class guys who are all straight, at least apparently straight. I mean, really just apparently straight. You know, with sexual preferences, we’re in this period of time and a few women and the women are there in a basic sense before ’80s explosion of the modes of feminism. They’re radical women. And they have you know, they’re all feminists in some basic sense. But it’s not the organized . . . battle of the feminisms has not yet occurred. Then what happens is the period of expansion, women and people of color coming into the movement. But white male guys are also quickly, both horizontally recruited and from below. So the number of people involved in the network is increasing. And both women and people of color didn’t go to Harvard Law School are interested in this because they’re looking for something that’s politically left, and they’re very curious about it. They’re looking for a progressive site of some type. The number of jobs is expanding. So it’s not a situation of cutthroat, but jobs for them are particularly available because affirmative action is completely the order of the day. The student numbers went up in the late seventies and now it’s the eighties. And the faculty members are just going up, up, up, up, up. [00:24:51]So the relative coherence of the theory project and the easy old boy character of the organizing project are both going to be dramatically destabilized by the arrival of these groups who are coming to us. So we’re recruiting them, say, Yeah, yeah, yeah, this is fantastic and it’s exhilarating and just incredibly thrilling. And it fulfills a basic fantasy of creating a, you know, a pluralistic, multicultural, multi gender . . . There’s [31.9s] no queer theory. The [00:25:26]Psychosocial CLS is [1.2s] just the moment before that. My research assistant, . . . Do you know who [00:25:32]Bill Rubenstein [0.4s] is? He was my research assistant. And I wrote Psychosocial CLS while he was working as my research assistant. And he read it. And, you know . . . a year and a year later he said, “you know, I’m really glad that you mentioned guy guy because, boy, was that everywhere in CLS.” And he then became a very serious gay liberation litigating advocate before he lost his organizing impulse as well, which he completely did. So that was not there yet. Both feminism and critical race theory. We’re arriving in a white male context, which was already divided generationally, but also it was divided methodologically, theoretically.

Abbey Marr [00:26:20] Can you talk more about what those divisions look like and how they played out?

Abbey Marr [00:26:23] So the older you were, the less pomo you were, and the younger you were, the more pomo you were. So the white guys are generationally divided. The young have an oedipal base. So the old guys . . . Oedipal relations are overwhelmingly oriented to the older people. And their Oedipal downward relations are ambivalent and complex. The young guys have a fairly straightforward problem, Oedipal problem, which is they’ve been brought into this thing that really is a great place. And the old guys are basically claim to be the one. The one. To be it. You know, the whole thing is them. So their basic experience is they are enormously important innovators and they would like students who will extend, develop their work. This is the normal attitude: students who will extend and develop and show . . . enrich it and expand it and show its relevance to almost all aspects of life. And basically that would be thrilling to have that done to one’s work. It’s a very, very basic attitude. And the young guys basically play a card, which is the card of the emerging postmodern currents, including a lit-crit feminist, postmodern current. So this is not [00:27:41]Catherine MacKinnon. [0.3s] This is the, you know, everyone. . . . So [00:27:46]Barbara Johnson [0.4s] so for example, was a person who was a Harvard English professor, who is a Derrida-influenced feminist, who would deny that she was either a cultural or a radical feminist, with some inklings in both directions. So she so this is feminism identified with Derrida or Jane Gallop, [00:28:07]The Daughter’s Seduction, Thinking Through the Body [3.2s] are two just astonishingly brilliant Derridian anti-identity politics feminist works. So the young guys have that, they have Derrida, they have Foucault, they’re totally tanked up. And they’re really saying to the old guys, “You are just so last week, I mean, it’s unbelievable. I can’t believe you still think that and you’ve never read this,” which was true. They did still think and they never read this. [00:28:38]Now women and people of color arrive. The women are divided between socialist feminists, liberal feminists, cultural feminists and radical feminists. And the porn wars have begun. [11.1s] So that’s totally polarizing on several levels because now there are enough feminisms and enough guys. So the guys, the old guys are not uniform because some young guys are really hip and you’re talking to one. So never forget it. So the old guys are split and the young guys are split very quickly because some of them are gay. Some of them are hyper intellectual and hate activism. Some of those people will become the best organizers. Weirdly enough, I mean, as I said, you know, I mentioned that already. It’s just you just can’t tell who end up having the organizing . . . . It’s not a gene the organizing grow into it is an activity. So and the the people of color are equally split. I mean, they’re really, really split. So there are liberal critical race theory orientations who were like liberal feminists, in many ways, there are people with a strong race consciousness orientation, which is fundamental and critical race theory splitting it. But then there are people who are oriented to self safe space and forms of organization based on the idea that black people need solidarity as they move into legal academia — an incredibly threatening and dangerous place. They need spaces where they can develop and support each other’s work. And they are not interested in challenging legal academia. They’re interested in challenging racism and societal evil through work that will be empowered by legal academia. And they’re not interested in trashing it. Versus people who have a race critique of legal academia, of whom the most important is Kim Crenshaw. She was the person with the most developed race critique of legal education. And those people are paradoxically interested in race coalition. So the paradox is the people who are . . . understand themselves as liberal activists and the cause of black people in the nation who need safe self space and want to ally with law schools as liberal places are not interested in social relations of a professional character except social relations. They’re not interested in political or academic relations with white people. They’re not racists. They love white people. Their politics is integrationist politics, but their academic strategy is to form this kind of thing. Whereas the people who have a really quite brutal and I would say brilliant critique of the racial character of legal academia are the ones who want to organize critical legal studies conferences and denounce the old guys. So again, this is the difference between temperaments, right? So this is the temperament is, you know, come to say, “you guys, you know, why is it why is it so awkward being black in this incredibly white, super straight environment? Why does it creep me out?” And then that person wants to organize a panel on that topic at a critical race, a critical legal studies conference, versus the person who wants to come and really hang with their white friends who are really, genuinely their friends and would never dream of sort of publicly putting them on the spot in this really nasty way. But there’s no intellectual, mutual or political thing. So you have all of these different things are emerging. Then quickly, we’re going to add the white women, Black women divide, which is really complicated, symbolized by the really, really, I would say completely unfair, but equally understandable black feminist attack on MacKinnon, which was just emerging at this point, which is really, really interesting. I am very critical of MacKinnon. I don’t know if you’ve read anything I’ve written about that, but I’ve written a lot about MacKinnon, who I think is a very, very important thinker, but . . . and who have relied. I’ve gotten a lot out of her work. In this case, I totally was on her side. So she was attacked in a way that really it was, you know, ridiculous, according to me. It was not ridiculous when dominance submission lesbian feminists attacked her. There, they were completely right. And everything they accused her of, according to me, was completely true, and she deserved it. But in this case, she really didn’t deserve it. But that was something that was emerging was a very strong black feminist and race conscious critique of white feminism. [00:33:10]So now we get the guys are all split, the women are split, and the people of color are split. So it was fantastic! It was just great! It was amazing. So these events would just spin with all these different positions being put on the table at the same time, people’s inner selves would be revealed in the tenseness of the moment. [24.0s] So the tension rises, people make slips of the tongue. So Dr. Freud was there everywhere. But people also lose their temper. And people sort of the energy is very powerful, and it has both an erotic undertone and also a very powerful undertone of Thanatos, the death instinct. And so it’s both are they’re very powerfully being played out now that it’s black/white where very powerful emotions are present in the black-white integrated exchange, which is active partly because neither . . . the blacks have endless experience of being the only black person in the room and, you know, accommodating and dealing with it. Now there are a bunch of them and they’re very explicitly there, and it’s expected that they won’t be like everybody else. They react to that in completely different ways. White men and women in general had never had sustained interaction with any black person in their lives except in the most formalized way where they might be very nice to the one black person in the room. They might be the only person in the room who befriended the one black person in the room. But this is really different. So it’s really different. And it was just and then the gender thing was the same. So everyone, men and women, are totally familiar with each other. It’s true, but this context was a new context for everybody. It’s the fulfillment of the seventies wave which is now crashing all around us. And it’s also the moment where the paranoid side is just spinning further and further out of control and being reacted against very strongly for the first time. Have you ever heard of the [00:35:18]Fact Brief? [0.5s] So in the pornography wars, a very, very important moment is when a group of women law professors at NYU and in New York who were long term feminist activists, civil libertarians, wrote something called the Fact Brief. I can’t remember what . . . . Faculty, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. You know, an ad hoc organization objecting to MacKinnon’s pornography writings, opposing it from the left on pro sex, anti puritanical and social science grounds, a combination that it was really flawed on all these levels. And that was a split among feminist law professors. And those feminist law professors were in CLS to one degree or another. So the MacKinnon strand, however, was or at least the cultural feminist strand . . . So you should read [00:36:13]”The CLS Fem Split” Robin West. It’s [2.5s] a reaction, partly to [00:36:16]”Psychosocial CLS.” [0.9s] So this is like five pages of, I think the only word. . .I think she would agree, of vitriol, just loathing of the whole CLS, white male style. But she was totally part of it. That is, she was I mean, in other words, it’s a world in which her contribution is being read by everyone and then it gets responded to by [00:36:39]Fran Olson. [0.3s] [00:36:40]So it’s hot. It just it’s really hot. I mean, it’s amazing. And then the event. But but it was not sustainable. So this is going on the generational, the gender politics, and then remember we’ve got our background or what’s going on in the on the ladder of schools — promotion, tenure and upward social mobility. And then what happens is repression. So we went too far. So at some point we went too far. And the grown ups really decided enough running in the halls. Someone is going to get hurt. Curfew. They just shut it down very effectively through tenure denial, basically. [40.5s] But first tenure denial and then by the job interview, which says “You went to Harvard. Ever take a course with Roberto Unger?” “Yes.” What did you think of it?” Literally. So the system . . . and [00:37:36]Jerry Frug [0.0s] . . . this should be . . . wrote an [00:37:39]article about this in CRCL, [1.2s] which is a very, very good article, which is just a description of a long series of incidents where CLS membership . . . and then [00:37:48]Carrington “Of Time and the River of Law and the river.” [2.7s] So Carrington was a sort of major part of this. A major part of it. He was the Dean of the Duke Law School at the time that he wrote the piece, you know, another law school that was hiring people every year. So can you imagine sort of being on the job market to go to Duke, what do you say? [00:38:07]So okay, so that was simultaneous with the repression and the internal effervescent explosion of conflict over identity politics and generational conflict all corresponded at the same time and produced basically burnout. [16.4s] And so there’s this period between 19, 1989, 90, 91, it’s still moving, moving, moving. And then the murder of [00:38:34]Mary Joe Frug [0.4s] was a very important event in the story, really important event for various reasons, not worth going into in the short time, but then it’s over. There’s this last event at Harvard in 1992 and then another one at Georgetown that [00:38:50]Gary Peller [0.3s] organized. But at the I guess it’s the ’92 Harvard event, which was enormous. [00:38:58]Mark [Tushnet] [0.1s] actually made a little intervention that was amazingly prescient. He said it’s a school, not a movement. If he was just talking in some other context, and it really struck me. I thought he was absolutely right. It was a moment where there were too many people, too diverse, and we were all giving our papers. So pushing back from the confrontation, pushing back from the claims, pushing and then and that. So that was that.

Abbey Marr [00:39:28] How much of that sort of life cycle do you think was unique to CLS and the way in which it operated in the legal academy and the times? And how much do you think it is the story of a social movement?

Abbey Marr [00:39:38] I think it’s a very common story of social movements. Very, very common. I mean, it’s always detail always different in detail. [00:39:45]But I think that basic story is not, including the oddness, so for a lot of the radical political movements of the Sixties, something in 1971 and 1972, when I started teaching at Harvard. So when I arrived in ’71, I got my job. I thought, this is really going to be quite difficult because life is so politicized in the academic world of the United States that I am going to have to deal every day with the question of what do I do? What am I willing to say? Where will the conflicts be? I arrived, and, hey, there was nothing. It was over. So the [37.0s] [00:40:23]Weather Underground [0.4s] [00:40:24]was underground. And basically, you know, [3.2s] [00:40:28]SDS [0.0s] [00:40:28]had been destroyed by the split with the Weather Underground. The [3.2s] [00:40:32]Black Panthers [0.4s] [00:40:33]had self-destructed and then the Attica prison uprising was repressed. So basically, and the system first of all, the Panthers, you know, the Panther leadership were I mean, I don’t think it’s wrong now to say in retrospect, they were simply murdered by the police in their apartment in Chicago, where there were five of them. [17.8s] [00:40:51]Hampton, [0.0s] . . . , the police arrived and they yelled for them to come out and they said “no.” They claimed a shot was fired, but no bullets went out the door and then they just used their automatic weapons and killed the five people. [00:41:03]Attica [0.0s] was the same thing. So basically this a prison riot and eventually they killed like 30 people. They just kill them. No more. [00:41:09]It’s over. So everything is over and it’s in a post. So that experience is very, very similar; nonviolent in our case, tenure denial is not violence, but the basic experience is the wind is gone from the sails, and we’re not becalmed. We’re not dead. We still have our friendships. We still have all the very powerful emotional bonds are still there, and there will be successor networks. So very quickly, the school, not as movement, but the different sub parts develop a lot of communal life. So the CLS network is still completely alive and it’s big, but it’s got no movement quality. [38.4s]

Jon Hanson [00:41:51] Thanks for listening to this episode of the Critical Legal Theory Podcast. If you’re enjoying the Critical Legal Theory Podcast, please subscribe to us wherever you get your podcasts. And please rate us and leave us a nice review to help us extend our audience.