PART 1: INTRODUCTION

“[T]here ain’t no such thing as a free lunch” … As it turns out, the [probation] services were provided without charge to the municipalities, but they were not free. In fact, the court is reminded of a different quote attributed to the inimitable Will Rogers: “It’s not what you pay a man, but what he costs you that counts.”

—U.S. District Court Judge R. David Proctor1

“Can you pay today?”

The question is a common refrain from Georgia state and municipal court judges handing down fines in misdemeanor cases. On a given day, their courtrooms are “packed” with defendants, all charged with low-level crimes such as speeding or public urination. Each case, often involving an indigent defendant who appears without legal counsel, typically concludes within minutes.2

When Hills McGee stood up in one of those courtrooms, he was unable to answer the judge’s question about payment in the affirmative. His $200 fine was simply more than he could afford. McGee, a disabled Army veteran, earns $243 of disability benefits each month from the Veteran’s Administration. He spends most of it on monthly rent at a rooming house; he does not own a home, car, or bank account. McGee receives regular treatment for bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, which make it challenging for him to maintain long-term employment. He had pled guilty to charges of public drunkenness and obstruction of an officer during court proceedings in which he did not receive counsel and was not read his rights.3

For McGee’s inability to pay his fine, the judge assigned him to “pay-only probation,” in which individuals who cannot afford their fines are “supervised” by a private probation company until they can pay. In McGee’s case, his probation would be supervised by Sentinel Offender Services, then one of Georgia’s largest private probation companies.4

Under Sentinel’s supervision, McGee’s financial difficulties soon worsened. Sentinel assessed McGee $186 in additional probation fees payable to the company, not the State. Still unable to afford the swelling fees, McGee was hauled back into court—this time by the probation company itself. A judge revoked his probation in 30 seconds, sentencing McGee to two months in jail because he was unable to pay the fees Sentinel had imposed. There was no assessment of whether he was indigent and no opportunity for McGee to speak. The public defender present later testified that she cried after the hearing, having watched him “run through the system like an animal.”5

***

A man was jailed for lacking funds to pay a $500 fine for burning leaves in his yard.6 Another, suffering from terminal liver disease, pled with the judge not to throw him back into solitary confinement for his inability to pay probation fees—to no avail.7 These stories all emblematize a system working by design. While Georgia, which contracts with over 20 probation companies, is a significant customer of the private probation industry, for-profit probation has taken root in states across the country.8 Its human effects are the product of a corporate model of probation run by profit-minded businesses that earn their revenues from the wallets of people on probation. The very people whose dollars keep the lights on in private probation offices are those in society with the least means. Their supervision by private probation companies, and the additional expenses it imposes, send them further into crippling, and sometimes inescapable, cycles of poverty. It also exacerbates pernicious, systemic inequalities—which reify existing societal power structures and their harmful underlying biases.

This paper aims to interrogate the private probation industry through a systemic lens. In particular, it focuses on the ways that corporate law and corporate power legitimate and enable this industry, and the manner in which the industry, in turn, exacerbates systemic injustices, re-intrenching status quo heirarchies. Following this introduction, Part 2 of this paper details the mechanics and harms of the private probation system and its intersection with systemic injustices. Part 3’s discussion of the blame frame analyzes three dominant narratives used to legitimate private probation. These narratives inform the examination in Part 4 of the role of corporate law and corporate power in establishing and perpetuating private probation. Part 5 concludes with proposals for solutions. Corporate law helps produce the harms of private probation by facilitating corporate power, enabling capture, and creating and legitimating unjust narratives, hierarchies, and systems of exploitation.

Part 2: The Rigged System of Private Probation

With what just happened in Minnesota with a Black man being shot and killed as a result of a traffic violation misdemeanor warrant, [it] reminds me of what happened in Georgia. We allowed private, for-profit [probation] companies to obtain misdemeanor warrants based upon violation of the terms of a [probation] sentence …. In states that allow private companies to police misdemeanor sentences, how many warrants for misdemeanor violations are outstanding?

—Attorney Jack Long, in correspondence to author9

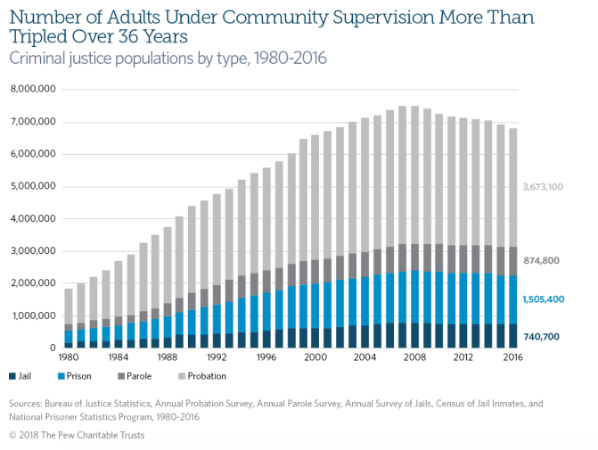

Probation has swelled in popularity within U.S. judicial and correctional systems as a less expensive and less liberty-invasive alternative to incarceration. Together with parole, it accounts for the largest portion of the U.S. correctional enterprise.10 At the end of 2018, over 3,500,000 people were on probation.11 Many of them are part of the pay-only probation model, in which an individual will be “supervised” until she becomes able to pay her court fine. Overtime, this model has proliferated in state courts. Adjusted for population growth, the percentage of U.S. adults on probation or parole in 2018 was over two times that of 1980—and is twice the number of people incarcerated.12

Figure 1: The Growth of Probation (Source: Pew Charitable Trusts Source: Pew Charitable Trusts)13

As the number of people on probation has increased, the attendant costs to already cash-strapped states have also been rising. The private probation industry was thus conceived. Private probation companies began emerging in the 1990s, lobbying state legislatures to permit them to establish contracts with state courts.14 The value proposition was simple: probation is expensive to your state; our companies will run it for free. States across the country jumped onboard, inviting companies into their courtrooms and handing over the reins to probation services. True to its word, the private probation industry did not bill states, yet its own revenues soared. In Georgia alone, probation companies were estimated to have taken in $34 million in fees annually.15 The source of the windfall? The people on probation.

With private companies administering probation, individuals on probation can pay hundreds or thousands of dollars in probation-related fees. Since probation companies earn their revenues from probationers, rather than the State, they have incentives to create significant financial penalties and extend probation terms to prolong the time each individual must pay monthly fees. This conflict of interest is particularly disastrous for so many defendants who were put on probation in the first place simply because they were unable to afford a nominal, court-imposed fine.

The most basic fee probation companies charge to those on probation, the supervision fee, ranges up to $150 a month.16 Sometimes, this fee can exceed the original fine levied—the very fee that the defendant was unable to pay in the first instance. In Louisiana, where 69% of people on probation earn under $20,000 annually, the average probationer accrued $1,740 in probation supervision fees alone in 2015, in addition to other probation expenses. By the end of their supervision term, the average person on probation in the U.S. still owed 48% of their supervision fees due to an inability to pay.17

Other probation conditions abound. As part of their supervision, a person on probation may be mandated to report to in-person meetings, and to pay for and wear an electronic monitoring bracelet. Many probation companies also require drug and alcohol testing, even for individuals with unrelated offenses that would not typically warrant such a condition. In those cases, the person on probation must pay for each test and for transportation to and from the testing facility.18

Due to the policies of probation companies, it is commonplace for people on probation to face punishment for “technical violations”—a key lever by which private probation companies amass revenue. Violations include failing to report, pay, or update one’s address. Given that the probation population experiences housing instability at rates higher than that of the general population, address requirements can be particularly onerous and stigmatizing.19 With each violation, a person on probation may receive another fee or a probation extension, a structure that incentivizes companies to make compliance with probation conditions difficult. As a result of technical violations, probationers may also lose their access to critical rights and benefits, such as their driver’s license, public housing, and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) eligibility.20

Company power is virtually unfettered. Probation firms may extend probation terms as they add more fees and await payment. Some states do not cap the amount of times corporations may do so.21 Ultimately, if a person on probation cannot pay, the probation company revokes probation and turns her over to the State for incarceration. This result serves the company’s bottom line but is deleterious for the individual and her family, society, and the goals of the criminal justice system. The Supreme Court, in Bearden v. Georgia, prohibited incarcerating people for poverty, but many judges do not make an assessment of indigency.22

Perhaps unsurprisingly, probation and prison are tightly linked. In 2017, 45% of U.S. state prison admissions came from probation and parole violations.23 While these trends do not solely reflect the actions of private probation companies, in many parts of the country, probation is almost entirely privatized. In 2016, for instance, 80% of people on misdemeanor probation in Georgia were supervised by a for-profit probation corporation.24

A System-Wide Lens

For-profit probation also intersects with and contributes to existing systemic injustices. The very structure of for-profit probation reifies existing disparities and exacerbates cycles of poverty.

Economically, people on probation are far more likely than the general population to live in poverty, making them particularly susceptible to harm from probation’s swelling fees. Roughly two-thirds of U.S. individuals on probation earn under $20,000 per year, and 38% earn under $10,000 annually. In New Mexico, for instance, over 80% of people on probation earn under $20,000 per year.25 Beyond fees themselves, probation conditions impose extra hurdles. Many lower-paying jobs do not afford employees the opportunity to take time off of work to meet reporting requirements. Other employees may not leave work to satisfy reporting requirements because of the stigma associated with the reason for taking time off, or due to the intimidation and threats created by some probation officers. Yet failure to report counts as a technical violation that can precipitate the amassment of more fines or lead to jail time.26 While onerous for anyone, these conditions can be debilitating for people already living in poverty.

Additionally, adults on probation are more likely than the general public to experience poor health and disability. People on probation die at a rate 3.42 times higher than those in jail, and 2.1 times higher than the general population—despite skewing younger than the jail population.27 One possible explanation involves high rates of substance abuse and overdose among probation and parole populations. Probation systems largely fail to treat this underlying health issue, which itself contributes to poverty and unemployment.28

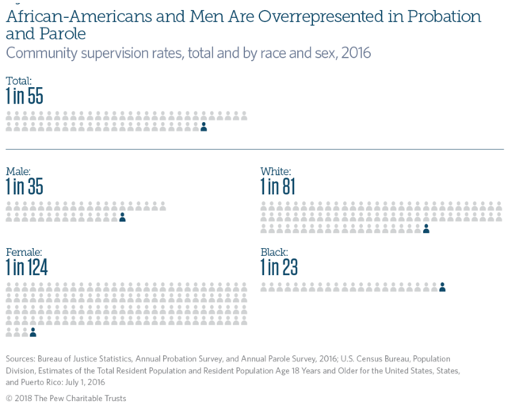

Probation also has strong intersections with race. People of color are disproportionately likely to be stopped by police,29 assigned to probation, sentenced to longer probation sentences, and have their probation revoked and face incarceration. These characteristics further exemplify inequity and effects of systemic racism.30

Figure 2: Intersections with Race and Sex (Source: Pew Charitable Trusts)31

Finally, those most affected by probation are often systemically disempowered from exercising their right to change the system. People unable to pay probation fees may be disenfranchised by the State due to their inability to pay.32 This reinforces centuries of political disempowerment and silencing of those with less power or property—and particularly people of color—who still today face illegal disenfranchisement. Since state legislatures create for-profit probation schemes, depriving people on probation of their right to vote makes it more likely that such policies may continue.

Part 3: Probation's "Blame Frame"

“We are you.”

-Judicial Correction Services33

For private probation to emerge and proliferate, the industry needed a story: a hook to ingratiate states to this new model of administering probation. Fortunately for the industry, following in the well-trodden footsteps of private prisons, such narratives proved abundant.34 The industry played on conceptions of criminality and poverty, and appealed to economic notions of free market primacy.

At a basic level, all three justifications share a common foundation: the theory of dispositionism advanced by the field of law and economics, and explained by social psychology.35 This concept assumes that people’s actions are stable, driven by preference and choice. As such, people on probation may be mistakenly understood to have played a significant role in choosing and producing their own life circumstances, a denigrating explanation to help justify the imposition of problematic probation conditions. Probation companies, by contrast, are viewed as simply obeying market demands, absolved of their responsibility in perpetuating the harm they create.

This notion is premised on a fundamental attribution error: Situation and forces beyond one’s control play a critical role in shaping decisions and identities. Meanwhile, probation companies act with agency and choice in creating the deleterious circumstances they impose through probation “supervision.”

Criminality

“We are you,” reads the archived website of Judicial Correction Services (JCS), a former Georgia-based probation company. “Your local office is the focus of our corporate structure. Office-level management lives in your community,” it says.36 These feel-good words belie something much more insidious. The words used by probation companies to describe themselves and those they supervise perpetuate the otherization of those suggested to be “criminal.”

Building on concepts of identity, the criminality frame deployed to legitimate probation uses dog-whistles of criminality to depict people on probation as dangerous and warranting punishment to protect society. Consider the JCS’s website language contrasting “offenders” with the “community.” This framing advances false notions of community that inherently otherize and play on bias involving race and socioeconomic status. By implication, those on probation are less so; while they live in the same community, they are outsiders and have an identity as a “criminal” that makes them “other.” Unsuspecting JCS website readers might be surprised to know how many of the “offenders” simply had run a red light.

Probation companies also lean on tropes of criminality in the ways they defend themselves in lawsuits. For instance, in a brief filed with the Supreme Court of Georgia in the case Sentinel v. Glover, Sentinel Offender Services defended its probation practices by suggesting that the plaintiff had benefitted from his probation arrangement. The company wrote, “[Jacob] Glover, and other probationers in Columbia County, voluntarily accepted the benefits of probation, including the opportunity to avoid incarceration.”37 The language suggests that Glover actually had a choice in going on probation in the first place. It also presupposes that Glover’s actions would have warranted incarceration, publicly framing the probation company through savior imagery and Glover through that of danger.

Poverty

In essence, for-profit probation criminalizes the act of living in poverty. Those who cannot pay fees are charged more; if they still cannot pay, they are incarcerated. This practice depends on narratives about poverty to legitimate itself.

In particular, choice-based dispositionism informs understandings of those living in poverty not as arriving there due to a complex array of situational circumstances, but through their decisions. It misconceives that those in poverty “are poor because they are lazy, do not improve themselves, cannot manage money, and abuse drugs or alcohol.”38 Emerging from poverty, under this view, is an action within a person’s control. This trope ignores the pervasiveness and complexity of systemic and situational contributors to poverty, leading people’s life experiences and economic status to be driven by factors that are often well outside their control.

Unfortunately, this view of poverty—advanced by the private probation industry—achieves traction due to its subtle pervasiveness in society. In a model of societal stereotypes developed by psychologist Susan Fiske to cluster groups of people based on their perceptions by others, those who are poor, welfare recipients, and the homeless rank lowest, and are more commonly seen as disliked and disrespected.39 The more those in poverty are otherized, the more their exploitation at the hands of for-profit probation is disregarded and normalized.

Policymaking Meta Script

Finally, another schema used to justify industry practices—known as the policymaking meta script—advances the idea of free markets over regulation.40 Under this theory, since regulators are subject to capture, markets work optimally when uninhibited. Leaning on this narrative, private probation companies highlight the ostensible cost savings they provide to taxpayers over court-administered probation programs. But private probation does not reflect a victory of economic competition in the free market system. Such a view overlooks the toll that its quest for profit takes on people on probation and the communities in which they live. While shrouded in the veil of economic theory, this meta script hides much more. Spurning regulation allows abuses to occur and legitimates a system in which the State hands over a major function without oversight into how it is carried out or the goals that it serves.

These frames, like others through which we understand the world, are shaped by cognitive biases, which create illusions of fairness, righteousness, and legitimacy. Often so pervasive that they are hard to detect, they form the foundation upon which corporate law and power are conceived and perpetuated.

Part 4: Corporate Law and the Rise of Private Probation

It’s about money, folks. It is about M-O-N-E-Y, dollar sign, dollar sign.

—GA State Representative Chuck Sims (R-169th) at a debate on probation legislation41

While couched in terms of its adjacencies to public institutions, the private probation industry is comprised of corporations. The industry’s growth and effects emblematize the danger of corporate power, and the role of corporate law enabling such power to take hold.

Corporate Law’s Effects

Private probation companies, like other corporations, derive power and legitimacy from various scripts and schemas. Beyond the dominant narratives of such companies detailed in Part 3, corporate law itself produces stories: in particular, that profit maximization to benefit shareholders behooves society and that shareholders require protection in ways that non-shareholders do not. This script—termed the corporate law macro script—helps explain corporate behavior that eschews social responsibility in the quest for profit.42

This macro script comes to life in the private probation context. First, consider shareholder primacy, the dominant corporate governance theory that prioritizes shareholder interests. This concept justifies the imposition of excessive, and often unnecessary, fees and probation conditions—all vehicles toward increasing corporate revenue to pad shareholder pockets. Indeed, the corporation is compelled to maximize profit under this model, ostensibly justifying its oppressive practices.

Where do individuals on probation fit in? The wellbeing of societal stakeholders, such as people on probation, is presumed to be accounted for by external forces. This assumption lays bare an illusion of corporate law. People on probation lack protection from these companies because the State has abdicated an oversight role and capture has provided corporations with free reign. Thus, corporate law’s essence creates the conditions in which the harms of private probation are created and perpetuated.

Second, the corporate law macro script manifests through corporate appeals to the public interest. In for-profit probation’s quest for profit maximization, it seeks legitimacy by framing itself as an ally of the public interest. To do so, it highlights its alignment with government, the savings it offers taxpayers, and the suggestion that it helps promote public safety. These narratives are harnessed by decisionmakers to justify market-based preferences favoring corporations.

The policy meta script and corporate law macro script together drive toward maximizing and legitimating probation privatization and profit-seeking behavior, while reducing and delegitimating regulation and the interests of those on probation. Private probation thus becomes a reflection of the interests of those in dominant positions of power.

The Dangers of Capture

Bolstered by these scripts, corporate power and law contribute to harm through capture. Capture—the idea advanced by George Stigler and others that regulation becomes so responsive to those with power so as to be “acquired” or captured—manifests with corporations generally, and is also endemic to private probation.43 The spectrum of capture ranges from shallow to deep, ultimately influencing people’s worldviews in a manner so ingrained that it is barely detectable. One’s very conception of self, relation to others, and view of market justifications can be captured, shaping societal tropes, structures, and operations.

Corporate capture by the private probation industry has been thorough. Consider HB 1040, a bill reported favorably out of a Georgia House committee in March 2020. The bill took aim at a 2015 Georgia criminal justice reform law mandating that people on pay-only probation only be required to pay up to three months of service fees to the company supervising their probation. HB 1040 sought to abrogate that law and raise the threshold to six months, doubling the amount indigent people could be required to pay. At a hearing, one of the bill’s six sponsors advocated vigorously, emphasizing that the average defendant is on probation for five and a half months, rather than three. On the chair beside him sat Clay Cox: President and CEO of probation firm Professional Probation Services; lobbyist for a Georgia private probation trade group; and former state legislator. When pressed by lawmakers during proceedings, Cox would not share the actual cost of pay-only probation supervision.44

Corporate capture has also pervaded the courtroom, as some judges act in ways that directly and primarily advance corporate interests. In Alabama, for instance, JCS successfully asked that courts charge all probationers a $10 set-up fee and a $35 monthly fee in initial Court Orders.45 What’s more, in some states, judges regularly hand blank Sentence of Probation forms to private probation companies bearing their signature. This allows companies to determine the duration of probation, total fine, and conditions imposed for people on probation. One Alabama probation firm regularly sentenced people to over two years of probation, despite the state practice of levying sentences of under 12 months. These company determinations are devoid of judicial oversight.46

It is unsurprising that the probation industry has achieved capture with such success. The industry boasts of numerous lobbying groups focused solely on probating probation company interests. These types of actors are more effective at shaping law and policy to serve their interests than groups dedicated to multiple issues, whose resources, personnel, and bargaining capital may be split among topics. The corporate “voice” of private probation comes to dominate, even when it justifies the inequality it helps foment.

As the private probation industry participates in deep capture, the narratives used enable the capture and the capture affirms the narratives. These dominant tropes develop a justice illusion that reifies existing schemes and sanctions blindness to the underlying injustices that both enable and are produced by it. Corporate power and the corporate law that underpins it make possible the rise of probation companies and harm they produce and magnify.

Part 5: It Takes "Guts": The Quest for Solutions

The problem with Georgia’s appellate court [regarding private probation] is that we haven’t found judges with enough guts to do anything.

—Attorney Jack Long47

The forces producing the abuses of the private probation industry are systemic. Ultimately, dismantling them requires systemic solutions, too. The painstaking work of changing dominant narratives and beliefs about individuals in the criminal justice system or living in poverty—let alone tackling the main drivers of poverty and income inequality—is part of a holistic solution. Another fundamental challenge involves interrogating and deconstructing the scripts of corporate law and policymaking that incite a drive toward profit and markets above all else. Delinking politics and law from business interests is a related pursuit, which can help be effectuated through laws and policies about lobbying and privatization. While these approaches can be difficult, they form a critical part of addressing the foundational, systemic problems at issue.

Another critical solution involves dismantling the private probation industry. This approach fails to address the root causes of the industry’s inception and growth, yet succeeds in providing an immediate curb to private probation practices. Indeed, some state legislatures have pursued this route, ending contracts with private probation companies. This action has resulted from advocacy by public interest groups, attention from the media, and challenges from lawyers. These partners play an important role in catalyzing change.

It is important to underscore the difficulty of imagining a successful private probation reform. It may be possible to increase oversight of companies and for companies to engage in less harmful practices. However, the incentive to maximize profits from probation will remain whenever states “outsource a part of our judicial system.”48 So long as companies earn revenue from those on probation, many problems caused by the industry are likely to persist.

In instances where legislatures have not terminated their private probation contracts, the courts themselves have also delivered some important victories. Most notably, in September 2020, the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that a private probation company acted in a quasi-judicial capacity by adding fees and conditions to an individual’s court-imposed probation term. As such, the company “was bound by the ‘strict’ impartiality requirement applicable to judges,” which the court easily concluded that the company violated.49 This decision demonstrates the potential for legal action to hold firms accountable and create change within the system. Yet change through the courts requires judicial resistance to strong forces working toward capture. Ultimately, change at the grassroots level, legislature, and judiciary all must work in tandem.

Conclusion

I asked for programs but … [probation] didn’t want to hear that I need help; they just gave me time.

—Individual on probation (requesting anonymity), serving years for conduct connected to drug dependence50

The private probation industry is broken. It has inserted a corporate profit motive into a judicial sentencing practice that has essentially criminalized poverty. Its effects have been staggering. Corporate law is at its core.

This title of this paper, Can’t Get Back Up, derives from a quote by Cindy Rodriguez, a woman in Tennessee whose first and only run-in with law enforcement for a shoplifting charge resulted in her assignment to private probation. She described her probation experience as “the most humiliating thing I’ve ever had to do in my whole life,” and added:

“I struggled to pay them the payments they needed every week. I ended up selling my van, because I was threatened all the time. If I didn’t make the payments, they were going to put me in jail. I lost my apartment, and it’s been a struggle ever since … There were times [my daughter and I] didn’t eat, because I had to make payments to probation.”

“No matter what I do,” she said, “I can’t get back up.”51

Further Reading

Alec Karakatsanis, Policing, Mass Imprisonment, and the Failure of American Lawyers, 128 Harv. L. Rev. F. 253 (2015).